Owen Matthews works in political risk insurance and is treasurer of the Queen’s Park and Maida Vale Conservative Association.

“The curious task of economics is to demonstrate to men how little they really know about what they imagine they can design.”

With this piercing insight, Friedrich Hayek, a titan of economic thought, reminds us of the hubris that plagues self-styled reformers like Gary Stevenson. This self-proclaimed “economist” – a term he wields with the carefree abandon of someone who’s never lost sleep over the viva voce examination of a PhD or the rigours of academic scrutiny – has built a cult following on YouTube, peddling tales of impending economic apocalypse driven by wealth inequality. His message? The rich are getting richer, the poor are doomed to stay poor, and only radical wealth taxes can save us. It’s seductive stuff for the politics-of-envy brigade, but scratch the surface, and it’s revealed for what it is: shallow, economically illiterate drivel, wrapped in the trappings of a grifter’s memoir.

Stevenson burst onto the scene with his 2024 book, The Trading Game, a rags-to-riches-to-rage-against-the-machine yarn that casts him as a working-class hero who outsmarted the fat cats at Citibank. He claims to have been the bank’s most profitable trader globally in 2011, raking in millions by betting on economic misery post-2008 crash. But his former colleagues beg to differ. In interviews and reports, they’ve dismissed his boasts as “delusions of grandeur,” insisting he was far from the top dog he portrays himself to be. One ex-colleague, Jeff Feig, declared flatly Stevenson’s claim about being the most profitable trader at Citi was “laughable and clearly just an outlandish fib” – a damning rebuttal from someone who was actually there. This isn’t just office gossip; it’s a pattern of exaggeration that erodes his credibility. If he can’t be trusted on his own backstory, why should we swallow his grand theories on fixing the economy?

The mental gymnastics Stevenson must perform to maintain his narrative are quite astounding. Here is a working-class lad from Ilford who clawed his way out of the poverty trap, making millions at an elite Wall Street bank, yet who insists the system is irrevocably rigged against everyone else. His own journey – from modest beginnings to millions by his mid-20s – is a living rebuttal to his claim that social mobility is dead. Yet he conveniently sidesteps this contradiction, preaching that only those born rich can succeed. It’s a remarkable feat of cognitive dissonance, and one that undermines his entire platform.

I’m willing to admit that perhaps my own aversion to Stevenson carries a personal tinge. As a fellow LSE alumnus with my own banking career in the rear view I have singularly failed to attain the heights of earning millions a year as he did – and there’s a certain sting in watching someone from the same academic stables parade their success while preaching that the system is rigged against all but the privileged few. Yet, this personal reflection only sharpens the clarity of the critique: Stevenson’s narrative is not just wrong; it’s a betrayal of the very opportunities that institutions like LSE can provide to those willing to work for it.

Take Stevenson’s “advice” to aspiring youngsters, for instance. When kids ask him how to get rich, Stevenson’s pearl of wisdom is as cynical as it is defeatist: “Have a rich dad.” This isn’t sage counsel; it’s a poison pill designed to crush aspiration before it even takes root. In Stevenson’s dystopian worldview, social mobility is a myth, hard work is futile, and the game is rigged from birth – a claim that his own ascent from Ilford to Citi’s trading floor spectacularly disproves. Never mind the countless entrepreneurs, innovators, and self-made successes who prove otherwise – from tech billionaires to corner-shop magnates who’ve built fortunes through grit, ingenuity, and, crucially, education and training. His mantra ignores the very engines of prosperity that conservatives champion: free markets, low taxes, and opportunity for all, underpinned by robust education and skills training that empower individuals to rise. By reducing wealth creation to inheritance, he peddles a victimhood narrative that absolves individuals of agency and condemns generations to welfare dependency. It’s not economics – it’s nihilism dressed up as insight.

And speaking of economics, where is Stevenson’s intellectual rigour? He’s never endured the gruelling peer-reviewed scholarship demanded of true economists, nor faced the relentless scrutiny that City economists endure daily in the crucible of markets. He’s never published a single paper in any academic journal of note, with his “expertise” resting on a brief stint trading interest-rate swaps at Citi and a self-uploaded master’s thesis on his website. A quick scan of scholarly databases turns up nothing; no peer-reviewed articles, no rigorous models, just viral videos and a book flogged for profit. This isn’t the mark of a serious thinker; it’s the hallmark of a populist showman, more akin to a TikTok influencer than a true economist like Hayek or Friedman. Real economists build theories on data, debate in journals, and propose policies grounded in evidence. Stevenson? He rants about inequality without the intellectual depth to back it up.

Worse still, his “solutions” are as vague as they are destructive. He bangs on about taxing the rich – proposing things like a 2.5 per cent levy on multi-millionaires – as if slapping higher rates on wealth creators will magically redistribute prosperity without killing growth. But where are the concrete plans? How does he address the flight of capital, the disincentives to invest, or the bureaucratic nightmare of enforcement? Critics from across the spectrum have lambasted his ideas as oversimplified and populist, lacking the depth to tackle complex issues like productivity stagnation or regulatory burdens. His framework ignores basic economic truths: that wealth isn’t a fixed pie to be sliced up by the state, but a dynamic force generated by innovation and enterprise. Tax the rich punitively, and you don’t empower the poor – you shrink the economy for everyone, as history from 1970s Britain to modern Venezuela attests.

At its core, Stevenson is a grifter, monetising misery for personal gain. His YouTube channel, with 1.5 million followers, churns out doom-laden content that preys on economic anxieties, while his book sales and speaking gigs line his pockets – all while he lives off the millions he made in the system he now decries. Detractors have called out his sensationalism, from podcasts decoding his “guru” status to forums debunking his claims as self-aggrandising fiction. He’s not a reformer; he’s an opportunist, exploiting the post-pandemic appetite for anti-establishment rage.

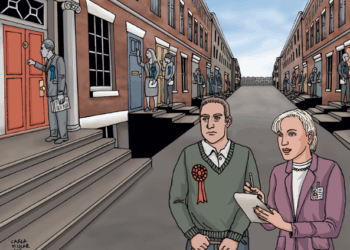

Conservatives cannot afford to ignore charlatans like Stevenson. His pernicious ideas – unchecked – erode faith in capitalism, fuel class warfare, and pave the way for disastrous policies like Labour’s wealth grabs. We must engage head-on: dissect his fallacies in debates, expose his hypocrisies in the press, and counter with our vision of empowerment through lower taxes, deregulation, and opportunity, bolstered by education and training as vital pathways out of poverty. Policies like expanding apprenticeships, reforming schools to prioritise skills over ideology, and incentivising vocational training can equip individuals with the tools to climb the economic ladder, just as Stevenson himself once did. Only by shining a light on this shallow sophistry can we reclaim the narrative and build a Britain where aspiration, not envy, drives progress. Stevenson may have traded derivatives once, but now he’s trading in illusions. It’s time to call his bluff.

![Donald Trump Slams Chicago Leaders After Train Attack Leaves Woman Critically Burned [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Trump-Torches-Powell-at-Investment-Forum-Presses-Scott-Bessent-to-350x250.jpg)