As Artificial Intelligence reshapes the academic landscape, faculty find themselves increasingly divided, torn between embracing its potential and resisting its perceived threats to pedagogy, ethics, and academic integrity. While some of us recognize the risks posed by artificial intelligence — including concerns about the left-wing bias in the source data itself — we choose to engage with its potential cautiously. Others have embraced an increasingly alarmist narrative, portraying AI as an imminent and overwhelming threat — and denigrating those of us who take a more measured view. (RELATED: Artificial Intelligence Requires Human Understanding)

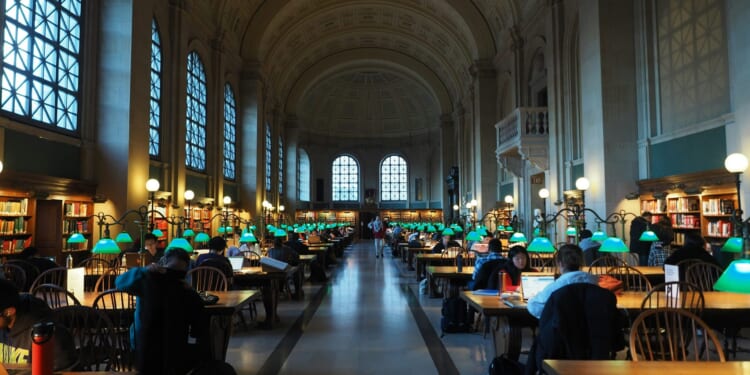

Recently, a colleague published an essay describing those of us who have attempted to implement aspects of Artificial Intelligence in our classrooms as being “unscrupulous and unserious” members of academia. Claiming that a teacher who uses AI-generated or assisted lesson plans is a “front-man for the Machine,” his essay suggests that “the teacher who relies on fake lesson plans will soon lose the ability to create real ones.” Declaring his rejection of the “cheap, disintegrated, and practically infinite information available on the Internet,” this AI-opponent vows to return to physical media. “If I really need to know (for instance) when Walter Raleigh was born,” he writes, “I can reach for a book.” (RELATED: AI Is Not the Monster — It Is a Mirror)

To be fair, this dedicated faculty member’s aversion to artificial intelligence is entirely understandable — even if his rhetoric and remedies veer toward the extreme. His concerns are echoed by educators nationwide, some of whom not only reject AI but now profess a broader retreat from reliance on internet searches altogether. A 2025 “Meta-Summary of Recent Surveys of Students and Faculty” on AI in higher education, which summarized the findings of surveys conducted in 2024 and 2025, offers insights into the future of AI in academia. Unsurprisingly, the findings revealed that while students have enthusiastically embraced AI and are using AI tools in their studies, faculty resistance remains strong and usage lags far behind. (RELATED: The AI Employment Apocalypse Is Only a Few Years Away)

Part of the problem is that many faculty members believe that they have not had enough input into university decisions on AI.

Part of the problem is that many faculty members believe that they have not had enough input into university decisions on AI. A new survey from the American Association of University Professors shows that a breakdown of shared governance around implementing AI has implications for the future of teaching, learning, and job security. More than 90 percent of the 500 AAUP members who responded to the survey last December indicated that their institutions are integrating AI into teaching and research, 71 percent said administrators overwhelmingly lead conversations about introducing AI into research, teaching, policy, and professional development, but gather little meaningful input from faculty, staff, or students: “Respondents viewed AI as having the potential to harm or to worsen many aspects of their work while ed-tech is at least ‘somewhat helpful.’ Eighty-one percent of respondents noted that they use some type of ed-tech, and 45 percent said they see it as at least somewhat helpful.”

Some large state institutions require a broad implementation of the new technology. The Ohio State University recently announced a new initiative to enable all students — no matter what their major — to graduate with proficiency in Artificial Intelligence: “Ohio State’s AI Fluency Initiative will embed AI education into the core of every aspect of the undergraduate curriculum, equipping students with the ability to not only use AI tools, but to understand, question and innovate with them.” By integrating AI education across the curriculum, Ohio State maintains that it is preparing students to be “creators and innovators, ensuring that they are well positioned to contribute to and lead the AI-driven economy.”

Despite Ohio State’s optimism, the AAUP study revealed that Artificial Intelligence is leading to faculty skepticism about the motives and consequences of embracing the new technology. One of the authors of the study told a reporter for Inside Higher Ed that “we on the committee have seen that AI in higher education is barely even functional and tech companies view higher education as a cash cow to exploit. Seventy-six percent of the respondents said it has created worse outcomes in the teaching environment; 40 percent said it is eroding academic freedom, and 30 percent said it is weakening pay equity.” Tying faculty bonuses and merit raises to the adoption of Artificial Intelligence has resulted in a two-tier faculty system and may be forcing some of the more recalcitrant faculty members out of the classroom.

Despite these concerns, those of us who are beginning to embrace artificial intelligence as a tool to enhance student learning recognize that our traditional role as educators needs to evolve. In an attempt to integrate AI into one of my own upper-division courses, each student was tasked with producing a 45-minute class presentation by creating a minimum of 30 AI-assisted PowerPoint slides. They were also asked to verify all presented data that they received from AI using existing U.S. Census Bureau data and other trusted data sources. The results were encouraging as the student presentations were visually striking, intellectually comprehensive, and deeply engaging. Most importantly, the data were accurate. As improvements have been made in data sourcing, AI data are increasingly dependable, and the original concerns about a left-wing bias in AI data sources and presentation have been greatly reduced.

Perhaps it is time for faculty to acknowledge that much of the resistance to embracing artificial intelligence in education is not solely rooted in concerns about student learning.

Student participation and enthusiasm have exceeded expectations for this course. It is rare for classroom presentations to elicit such sustained attention and interaction from student peers. Yet this semester, each student brought their data to life through AI-assisted PowerPoint slides that featured beautifully rendered bar graphs, dynamic layouts, and visually stimulating designs. Embedding short film clips into their presentations brought an additional layer of vibrancy. The integration of AI tools allowed students to experiment with aesthetic choices and presentation formats they might not have attempted. The result for each student was a slide presentation that was not only intellectually rigorous and informative but artistically compelling.

Perhaps it is time for faculty to acknowledge that much of the resistance to embracing artificial intelligence in education is not solely rooted in concerns about student learning. At its core, it often signals an unwillingness to reconsider the conventional role of the educator, coupled with a perceived erosion of an ability to use the classroom as a space for ideological influence — providing a platform for shaping belief. For decades, our authority has depended upon our role as “gatekeepers” of knowledge and facilitators of intellectual growth. The rise of AI challenges that model — offering students instant access to information, adaptive feedback, and even assistance in crafting arguments or solving problems. The influence of faculty bias in classrooms can be significantly reduced as Artificial Intelligence fosters a more democratized learning environment, leaving less space for the left-wing politicization that has permeated university classrooms for decades.

This shift forces us to confront an uncomfortable question: How do we preserve the human dimension of education — curiosity, mentorship, ethical debates — when technology begins to “take over” the domain that we once considered ours? Faculty members need to be the ones answering that question. If the faculty response is simply to try and bolt the door against encroaching technology, they give up the opportunity to reimagine their role in ways that can be both meaningful for their students and rewarding for them.

READ MORE from Anne Hendershott:

Not in the Neighborhood: Ms. Rachel’s Radical Departure From Mr. Rogers’ Moral Compass

![Trump, Hegseth to Get Troops Paid Despite Dems Voting Against it Eight Times [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Trump-Hegseth-to-Get-Troops-Paid-Despite-Dems-Voting-Against-350x250.jpg)