Dr Sarah Ingham is the author of The Military Covenant: its impact on civil-military relations in Britain.

On Sunday the annual Service of Remembrance will take place in Whitehall.

The Two-Minute Silence beginning precisely at 11 o’clock with the toll from Big Ben, the bugle, the distant echo of gun salutes and Elgar’s “Nimrod” all combine to create a solemn soundscape as Britain honours the war dead.

The ceremonial that has grown up around the Cenotaph is now more than a century old. From the ancient Greek meaning “empty tomb”, the monument that was originally designed as a temporary commemoration of the First World War instead has become an enduring tribute to the fallen of all Britain’s wars.

The wreaths of red poppies will be laid as usual. For the fourth year, this ceremony will be led by the King. Elizabeth II, who served in the ATS, personified the Second World War generation. With her presence, what was memory was not yet history.

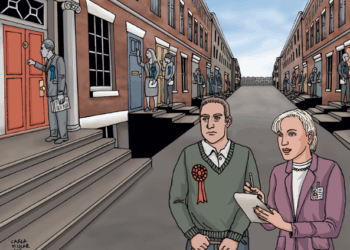

The final generation of young men who did their National Service are now in their eighties. With the end of compulsory conscription, military service reverted to its traditional norm: a job undertaken by a professional caste, on behalf of civilian society but apart from it, swearing allegiance to the Crown but subservient to the government of the day.

Earlier this week the Chief of the Defence Staff was out and about in Whitehall selling poppies. Air Chief Marshal Sir Rich Knighton spoke of how Forces’ personnel are ever on standby, including soldiers in Estonia, air crew at RAF Coningsby and Britain’s submariners.

Raising £54.1 million last year, the Royal British Legion’s Poppy Appeal reflects the civilian public’s tangible support for Armed Forces’ personnel, veterans and their families.

On Monday, PM Starmer hosted a reception at Downing Street for the Armed Forces, cadets and veterans. Like most politicians keen to be associated with martial can-do, Sir Keir spoke fluent platitude: “celebrate your service”; “profound thanks”; “values”. Veterans are a “national asset”.

Fine words neither butter parsnips nor finance warships. Defence remains woefully underfunded, symbolised by how crews on Britain’s Vanguard submarines are now routinely expected to undertake what were previously unknown six-months-plus tours of duty to ensure the country’s nuclear deterrent deters.

Just ahead of June’s NATO summit, the government made a commitment to raising the defence budget to 5 per cent GDP, an astonishing leap from last year’s 2.4 per cent. But like the Chancellor’s “fully costed and fully funded” pre-Election spending promises, all is not what it seems. The 5 per cent comprises 3.5 per cent for the “core” budget and 1.5 per cent for “defence and security-related investments” – whatever that means. (Rural broadband has been mooted) And the target is not expected to be reached until 2035 – which makes it meaningless.

The chronic shortage of funds for defence highlights the treasonous folly of paying Beijing-friendly Mauritius for the privilege of handing over the Chagos Islands. The estimated cost to the British taxpayer is a minimum of £100 million a year. This will come out of the defence budget – and would be better spent on improving the sub-prime state of Forces’ housing.

Almost 30 years ago, the Army came up with a reciprocal concept that expressed civilian society’s moral and practical support for soldiers who were serving the nation – the Military Covenant. In the essay in Army doctrine which first described the Covenant, this sense of mutual obligation between soldiers and the wider civilian nation was best expressed at Armistice “when the nation keeps covenant with those who have made the ultimate sacrifice, giving their lives in action.”

On Sunday, at many war memorials in the villages, towns and cities across Britain, people will gather to remember the soldiers, sailors, aircrews and submariners who have died in the country’s defence.

Poppies originally symbolised the so-called Great War. Far from celebrating the horrors of war, they represent support for Forces’ personnel. David “Calamity” Lammy’s lack of poppy compounded his mistakes at Wednesday’s PMQs, tipping it into a comedy of errors.

Outside Remembrance, attention is seldom paid to war memorials. They are such a familiar part of Britain’s streetscape, they blend into the background. However, they are imbued with such reverence that few have objected to the draconian legislation protecting them.

The new Crime and Policing bill makes it an offence to climb on any war memorials that English Heritage designates National Heritage Category 1 sites. This includes the Cenotaph. The proposal follows legislation in 2022, which made causing criminal damage to war memorials, or to wreaths and flowers, a criminal offence. The maximum penalty remains 10 years’ imprisonment.

The legislation followed “widespread upset” about the damage and desecration that occurred in 2020 during the Black Lives Matter protests. Veterans and serving soldiers who scrubbed graffiti off the Cenotaph described the monument as “hallowed ground.”

However imperfect defence policy is, despite the shrinking budgets and the reduced numbers, the British people recognise the debt they owe to the men and women of the Armed Forces, both present and past.

They have fought our wars and are keeping our peace. We will remember them.

![Texas Trucker Busted with 23 Illegals Stuffed into the Cab of His Big Rig [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Texas-Trucker-Busted-with-23-Illegals-Stuffed-into-the-Cab-350x250.jpg)

![Keith Ellison Caught Promising to Fight State Agencies for Somali Fraudsters [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Keith-Ellison-Caught-Promising-to-Fight-State-Agencies-for-Somali-350x250.jpg)