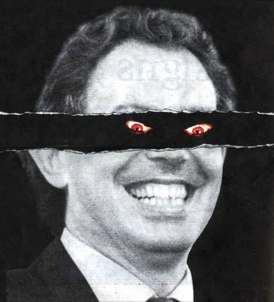

New Labour, New Danger.

For the ‘97 campaign, Saatchi produced a poster of a rather demonic-looking Tony Blair.

It was hounded for its use of negative campaigning and dismissed by polite society as bad taste and a sign of desperation. The Advertising Standards Agency determined that it portrayed Blair in a “dishonest and sinister” light and ordered its withdrawal. Sir Tony went on to win a decisive victory at the polls and the rest, as they say, is history.

And to this day he remains a revered elder statesman, and most of the flak he does get is not from the right, for his liberal excesses, but from the left – for Iraq, for public-private partnerships, for being the closet-Tory who squandered Labour’s chance for “real change”. Likewise, it never fails to surprise me how many Conservatives I know cite Blair as their favourite Labour PM. I want to make the case that behind the centrist façade and disarming accent he was in fact as bad as the rest of them.

In many ways, he was worse.

Let’s get one thing clear.

New and Old Labour’s means and messaging were different but the ends were always the same. Blair said from the start that his aspiration was to create a winning synergy of socialist values and economic realism. He had correctly identified that, on the whole, it’s the left’s idealism and not its values that loses elections. Most voters have a leftwing value system and a rightwing worldview.

In other words, people want fairness but they’ve been round the block too many few times to fall for pie-in-the-sky rhetoric. An excellent bit of political nous – so the narrative goes.

But what that picture of Blairism doesn’t tell is the whole story.

The economic framing omits his interest in social policy and social engineering. Shrewdly so, given the former PM’s social agenda was less aligned with public opinion. First and foremost, this is the man who let the cat out of the bag on immigration. Net immigration was in the tens of thousands under Thatcher/Major and even Old Labour. It’s been in the hundreds of thousands ever since Sir Tony took the wheel. Our Reform problem has its origins in the 1997 election.

Blair then proceeded to implement the “buck stops with no one” model of public services when things go wrong. He was a driving force behind the UK’s adoption of depoliticised managerialism in day-to-day decision making, where the same people run the show regardless of which party wins the election. Intangible and unaccountable partnerships defined his premiership.

Quangos were always on the up.

On education, he created the cult of the degree and made plumbers an endangered species. On the economy, he introduced the minimum wage (over 20 per cent of working-age adults in Britain are economically inactive today) and presided over endless growth in red tape – except where it was needed. His Chancellor went on a spending spree instead of saving for a rainy day and left Britain exposed when something or other hit the fan in the late 2000s.

And then there’s the constitutional meddling.

It was Blair who established a Supreme Court in America’s gridlocked image and brought a culture of judicial activism to British courts, where in the past they had shown an element of deference to Parliament’s chosen Government. It was Blair who ended political control of judicial appointments, replaced it with an independent commission, and made the judiciary a closed system. It was Blair who introduced the devolved governments that have only widened the gap between Scotland and Wales and their fellow Brits in England – and by the way strengthened the nationalist cause by giving anti-unionists the perfect soapbox to complain from.

So who is Tony Blair?

He is the man who won Labour three consecutive general elections. His ideological clone has just led Labour to third place in a South Wales constituency. Clearly, Blair is someone from whom we can learn a great deal – about party management, about sensing the public mood, about telling a story that connects with voters.

But he is not someone we should admire or revere.

It was a mistake to leave his legacy untouched when our party had the power to change it.

No one went to the polls in 2024 thinking, ‘the Tories didn’t repeal the Constitutional Reform Act, I’m voting them out’. But that doesn’t mean Blair’s policies didn’t contribute to the more material concerns voters have that did lose us the election and now leave us where we are in the polls today.

![Scott Bessent Explains The Big Picture Everyone is Missing During the Shutdown [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Scott-Bessent-Explains-The-Big-Picture-Everyone-is-Missing-During-350x250.jpg)

![Virginia Democrat Candidate's Leaked Texts Are So Bad Even MSNBC Turns on Him [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Virginia-Democrat-Candidates-Leaked-Texts-Are-So-Bad-Even-MSNBC-350x250.jpg)