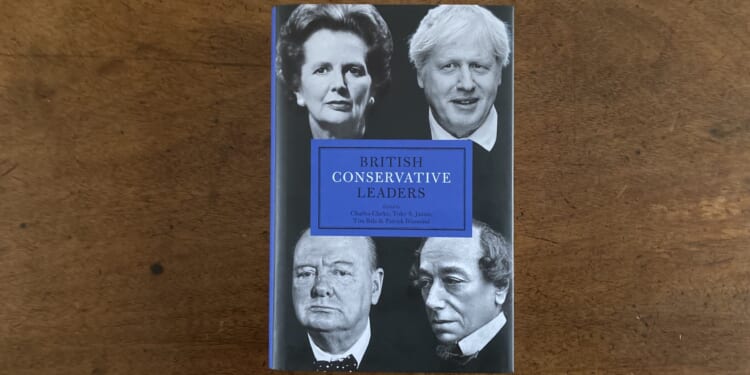

British Conservative Leaders edited by Charles Clarke, Toby S. James, Tim Bale & Patrick Diamond

The brief life has much to recommend it. Brevity is the soul of wit, allowing both writer and reader to delight in whatever is most amusing and characteristic about some figure, without having to spend many hours pushing through thickets of detail.

This book contains brief lives of all 24 leaders of the Conservative Party from Sir Robert Peel to Rishi Sunak. Here one can enjoy Angus Hawkins on Lord Derby, Robert Saunders on Benjamin Disraeli, John Charmley on Winston Churchill, David Dutton on Anthony Eden, D. R. Thorpe on Harold Macmillan and John Campbell on Margaret Thatcher.

But before the brief lives start, the editors of the volume devote over 80 pages to drawing up “frameworks for assessing leaders”.

They admit that assessing leaders is “messy and complicated”, but claim the answer to this difficulty is to set up a “statecraft framework” to see how well or badly the leaders performed such tasks as moving the party “towards the goal of winning and maintaining office”.

A pinnacle of absurdity is reached in a chapter written by Charles Clarke, who while serving in 2003 as Education Secretary attracted a certain amount of opprobrium by declaring, with evident sincerity, that “education for its own sake is a bit dodgy”.

Clarke presents a series of league tables in which the performance of Conservative leaders is ranked according to the number of votes and seats they gained or lost at each of the 48 general elections between 1835 and 2024.

When seats gained are taken as the measure, Churchill is in 17th place, below Home, Heath, May, Hague, Macmillan, Eden, Johnson and many others.

But Churchill is a world historical figure, which none of the others is. There is no harm in reminding us, as Charmley does, that during the Second World War Churchill took “very little interest in his party or, indeed, in electioneering”.

It would, however, be ludicrous to suggest that the Labour landslide of 1945 diminishes Churchill’s greatness as a war leader, which rests on his magnificent defiance in 1940.

In that tremendous crisis, all his faults suddenly became virtues. He loved war, and war had come. He had often rebelled against his party, and the country now needed a government above party, in which Labour men like Clement Attlee and Ernest Bevin would be happy to serve. He was a fervent imperialist, and the full resources of the British Empire must be mobilised.

None of this applied in 1945. Charmley reminds us of Lord Beaverbrook’s observation, made as early as 1942, that just as Liberalism had been the main victim of the Great War, so Conservatism would be the victim of this one.

The Second World War was a collective war, every field of life dominated by the state. By 1945 people were utterly tired of fighting, and looked to the state to apply collective solutions to the problems of peace. As Charmley observes,

“Never knowingly weary of a war himself, Churchill seems to have been blissfully unaware that, for most of his fellow countrymen, its ending was a blissful relief. The thing they looked forward to was the thing that bored him – the details of post-war reconstruction.”

The usual Tory tactic of warning that Labour’s leaders lacked government experience could not be used against Attlee, Bevin, Herbert Morrison and the rest. For the past five years they, along with one notable Tory, Rab Butler, had been running the Home Front, while Churchill ran the war.

Churchill warned during the 1945 election campaign that Labour would need a “Gestapo” to implement its policies. Such exaggerated language made him sound old and out of date.

The rejection in 1945 of Britain’s victorious war leader was perhaps the most democratic moment in our history, demonstrating as it did the independence of a free people.

Such possibilities tend to be forgotten if one attempts, as Clarke does, to make seats won the criterion of success. It is true that winning and retaining power has always mattered a great deal to the Conservative Party.

But it is also true that failure can be invaluable in helping one to judge when to give ground and when to stand firm. Sir Keir Starmer is just now out of his depth as Prime Minister in part because in his earlier career he never failed, so could never learn the lessons of failure.

The Conservative Party concluded from its defeat in 1945 that it would have to make some sort of accommodation with socialism, and Butler duly supervised the necessary work on this difficult question.

Eden is often treated with condescension by historians. In Dutton’s account we are reminded that after at last succeeding Churchill in 1955, he called a general election and won it with 49.7 per cent of the vote, a score never since equalled, the party even managing to take a majority of the seats in Scotland.

The Suez disaster followed in 1956, and destroyed his premiership. Dutton agrees with David Owen that Eden was at this time taking medication which “had the effect of turning him into the sort of leader many of his critics wanted – bold, single-minded and decisive”.

Casting aside his habitual caution, Eden confronted the Egyptian leader, colluded with Israel, misled the American President and lied to the House of Commons: a series of appalling misjudgements.

Macmillan was the beneficiary of these blunders, and won the general election of 1959 with 49.4 per cent of the vote. Thorpe observes that Macmillan managed until near the end of his time in office to follow Walter Bagehot’s precept:

“A great premier must add the vivacity of an idle man to the assiduity of a very laborious one.”

Disraeli is the most fascinating figure in the book. He is unintelligible to management consultants, and naturally scores badly in Clarke’s league tables.

Saunders reminds us that Disraeli hoped to be the next Byron, failed as a poet, but at length breathed new life into the Conservative Party:

“For Disraeli, the great institutions of Church, monarchy and aristocracy were not brakes on popular power to be defended against a turbulent and volatile mass; they were popular institutions, which had only to appeal to the imagination of the people to stand on a firm foundation.”

By putting through the Reform Bill of 1867, he demonstrated that the Tories were a popular and national party which had nothing to fear from the working class, whose interests it would defend more staunchly than the Liberals did. As Saunders says,

“No Conservative leader has shown a surer feel for the theatre of British politics, or exerted such a lasting hold on the popular imagination.”

Disraeli, we are reminded, prided himself on his management of men. He was a great parliamentarian who spent long hours meeting backbenchers, flattering their vanities and assuaging their concerns.

Boris Johnson’s love of political theatre, his teasing of the prigs and easy communication with the working class, place him in the tradition of Disraeli.

But as Johnson admits in an interview at the end of this book, his Achilles’ heel “was insufficient respect for the institutions of Parliament and the whole system – and a kind of cocky impatience with it all.” He looks back with nostalgia to his monarchical position as Mayor of London, which suited him better.

After entering the Commons in 2001, Johnson remained editor of The Spectator, did not work his passage in the Chamber or in committee, nor did he learn how things worked by serving in the Whips’ Office, nor was he inclined to spend time in the tea room or the bars.

Once he was Prime Minister, it was too late for him to repair these deficiencies in his political education, and while Covid raged he could have no proper contact with his backbenchers, who instead concluded from social media that things were going irretrievably wrong.

But how easy it is, as a commentator, to adopt without realising it the mentality of the management consultant, and begin implying that if only the politician under discussion were as clever as the commentator, all would be well.

It is actually extremely hard to remain PM for more than a few years. We have a system which ensures that the grip on power of whoever is in Downing Street is always precarious.

He or she is the people’s tenant, and when the people have had enough, out he or she goes.