“I would have been hailed with approval if I had died at 50,” W. E. B. Du Bois wrote upon turning 90. “At 75 my death was practically requested.”

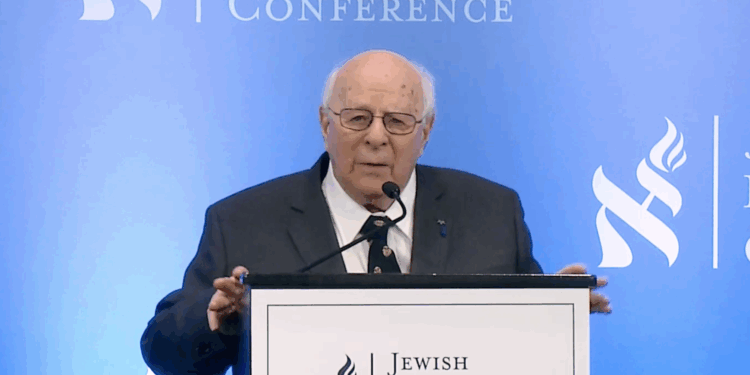

Norman Podhoretz, another well-traveled intellectual who also lived to 95, could have said something similar about his own life. He died on Tuesday a month shy of 96.

Du Bois went from a Berkshires birth to a funeral blessed by a witch doctor in Ghana, from mocking Marcus Garvey’s Pan Africanism to renouncing his U.S. citizenship and figuratively embarking on his own Black Star Line to Africa, from Harvard University to the Communist Party, and from co-founding the NAACP to loudly advocating for racial separatism.

Podhoretz took over as editor of Commentary magazine in 1960 and promptly took it further left. And then society moved left more quickly in the ensuing decade. Podhoretz shifted, relatively and absolutely, right. He became a Reaganite, then an enthusiastic backer of regime change in Iraq during the Clinton administration through the notorious Project for the New American Century’s “statement of principles,” and, in life’s final act, something more than a Two Cheers for Donald Trump Republican.

“I thought the animosity against him was way out of proportion and, on the right, a big mistake,” he told the Wall Street Journal’s Barton Swaim in 2021. “I went from anti-anti-Trump to pro-Trump … I still think — and it’s been the same fight going on in my lifetime since, I would say, 1965 — I still think there’s only one question: Is America good or bad?”

Podhoretz traveled further than 95 years would normally allow. And, like Du Bois, this gained and lost him well-wishers and comrades. He even wrote a book about this phenomenon that he mistitled Ex-Friends.

The likes of Lionel Trilling, Lillian Hellman, and Norman Mailer were never his friends. They were his comrades. A set of shared political beliefs tethered them. When he veered from those beliefs, they steered clear of him. One does not glean the impression from reading the book that Podhoretz regarded such treatment of an old “friend” as petty. He accepts the idea that, if people disagree on important yet impersonal matters, then best run the end credits on the association. Still, he could appreciate the silliness of it all.

“In my case, because I seemed to be destroying rather than advancing my career, the theory circulated that I had gone mad,” he said of his political epiphany that began in the latter part of the 1960s. “One of my best friends at the time even tried to persuade my wife to have me committed to a mental institution before my clearly self-destructive actions had a chance to reach their consummation in a literal self-destruction — that is, suicide.”

But Podhoretz in this second act influenced presidents rather than merely other public intellectuals. Another p-word — patriot — came to characterize his outlook. From the 1960s onward, a defense of America against its detractors broadly colored his writings.

Norman Podhoretz the American was more commonly thought of as Norman Podhoretz the New Yorker. And that New York intellectual scene that embraced and rejected him? Podhoretz outlived it. He never quite escaped it.

In The Souls of Black Folk, Du Bois spoke of an African American dual consciousness: “Two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body.”

Podhoretz revealed his version of this — call it maybe The Souls of New York Jewish Intellectuals — earlier this year at The Free Press. Therein, he called Brooklyn his spiritual home even though Manhattan had remained his physical home since the 1950s. He wrote of both providing sustenance to him even as they both threatened to tear him in two.

“On one side of the river lay a troubled, crime-ridden slum, split in thirds between Jews, Italians, and blacks. A gang stood on every street corner; violence and drinking were ubiquitous,” he explained. “On the other, Manhattan: a glittering fortress of class and intellect.”

Podhoretz spent a career uneasily straddling the East River. He ultimately became more patriotic than parochial. That aspect of his 95-year journey seems most overlooked in this week’s reflections upon his life.

![Florida Officer Shot Twice in the Face During Service Call; Suspect Killed [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Inmate-Escapes-Atlanta-Hospital-After-Suicide-Attempt-Steals-SUV-Handgun-350x250.jpg)

![Keith Ellison Caught Promising to Fight State Agencies for Somali Fraudsters [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Keith-Ellison-Caught-Promising-to-Fight-State-Agencies-for-Somali-350x250.jpg)