KYIV, Ukraine — As Ukraine enters a fourth winter of all-out war, the besieged country is facing a mounting crisis that has little to do with Western weapons or Russian firepower: Kyiv is running out of able-bodied men.

Acute recruiting shortages, soaring desertion figures and a steady outflow of draft-age citizens to Europe have left Kyiv struggling to hold a 1,200-kilometer front line against a Russian army that, despite staggering losses, maintains a consistent manpower advantage.

According to data cited by former lawmaker and serviceman Ihor Lutsenko, more than 21,600 cases of desertion were recorded in October alone, a wartime record. Meanwhile, many incidents likely never make it into official statistics.

A separate review by the group Frontelligence Insight found more than 235,000 AWOL files and 54,000 desertion cases opened as of Sept. 1. The analysts caution the figures reflect bureaucratic procedures as much as missing troops. The number of soldiers actually absent, they say, is roughly 150,000.

Still, the estimate is an alarming figure for a country fighting for survival.

Exhausted units, endless deployments

Frontelligence warns that if the problem is left unaddressed, it could become a “serious strategic risk” for Ukraine’s ability to hold the line.

Kyiv has oscillated between punishment and pragmatism. On one hand, lawmakers have stiffened penalties for desertion and commanders have launched periodic crackdowns on draft dodging in major cities.

On the other hand, the government quietly created a pathway for some deserters to come back.

A law that entered into force in late 2024 allowed first-time AWOL offenders to file for reinstatement online and return to a reserve unit with pay and benefits restored.

Despite those efforts, the crisis has become more pronounced on the battlefield.

As Russian forces tighten their grip around the strategic hub of Pokrovsk in Ukraine’s eastern Donetsk region, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy recently admitted that Ukrainian defenders are now outnumbered eight to one.

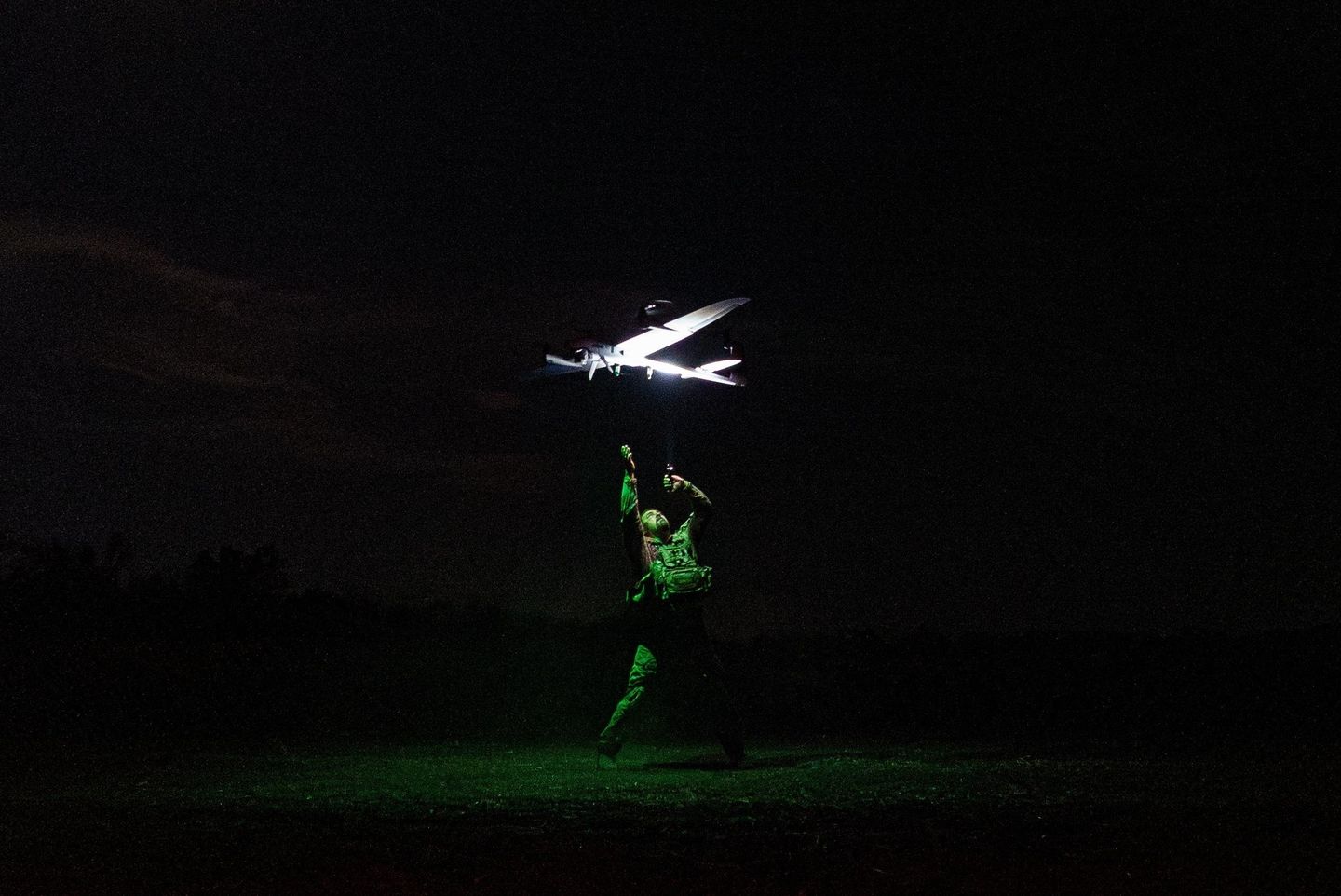

Units often remain at their positions for weeks or months without rotation and, in some cases, have to be resupplied in water and food by drone drops.

After more than three-and-a-half years of conflict, the initial groundswell of patriotism and the thousands of volunteers that thronged recruitment offices in February 2022 has faded, replaced by exhausted veterans and forcibly mobilized men.

Former Defense Minister Rustem Umerov acknowledged that only 12% of new recruits in 2024 joined voluntarily, while hundreds of thousands of men aged 18 to 60 have quietly slipped out of the country, seeking refuge in the EU despite martial-law travel restrictions.

A controversial August 2025 decree allowing men aged 18 to 22 to leave Ukraine legally until their 23rd birthday, triggered a fresh spike in departures.

Germany, already home to more than 1.2 million Ukrainian refugees, reported a notable increase in young male arrivals, prompting Chancellor Friedrich Merz to urge Kyiv to “keep its youth in Ukraine.”

Meanwhile, Moscow shows no sign of manpower fatigue.

Fresh bodies for Russia

British officials estimate Russia’s total casualties at close to one million since 2022, yet the Kremlin continues to sign 50,000 to 60,000 new recruits every month, buoyed by lucrative cash bonuses, subsidized housing and the mass incorporation of prison inmates.

Kyiv, by contrast, struggles simply to retain willing soldiers. “This is the army’s number one problem — and therefore the country’s number one problem,” Mr. Lutsenko warned.

A recruitment officer with the 423rd Separate UAV Systems Battalion told The Washington Times the collapse in enlistments is driven by overlapping factors: physical and psychological exhaustion, delayed rotations, and economic pressures on families left behind. But he also points to a deeper structural flaw. Ukraine, he says, lacks a system-wide personnel-screening process capable of placing recruits where their skills are most valuable.

“A person with strong technical or IT training can end up in a role that makes no use of those skills,” he notes—an especially crippling inefficiency for a military increasingly reliant on drones, electronic warfare and autonomous systems.

The question now haunting Western capitals is simple: even if Ukraine receives the weapons it needs, will it have enough soldiers to use them?

All of this plays out against a rapidly shifting backdrop in Washington.

The National Defense Authorization Act for fiscal year 2026 signed by President Trump Thursday reauthorizes the Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative at $400 million per year in 2026 and 2027.

It is a far cry from the tens of billions approved earlier in the war, but still a lifeline for ammunition and air-defense interceptors.

Trump tightens screws on Kyiv

Mr. Zelenskyy is under pressure from Mr. Trump to hold elections despite martial law.

The Ukrainian president has said he is ready to go to the polls within 60–90 days if the United States and European partners can guarantee security and fund the process, but has warned that “external pressure” will not dictate Ukraine’s constitutional choices.

For Ukraine, the intersecting trendlines are dangerous. Russian losses are enormous, but Moscow still fields more men along key sectors of the 620-mile front.

Kyiv’s decision to let its youngest men leave, combined with an exhausted veteran corps and a justice system clogged with nearly 300,000 AWOL and desertion cases, raises questions about how long the current force-generation model can last.

Meanwhile, U.S. support has shifted from open-ended “as long as it takes” rhetoric to carefully budgeted sums and overt pressure for a settlement.

Congress has guaranteed some money for weapons into 2027; but the Trump administration is signaling that Ukraine is expected to arrive at the negotiating table sooner rather than later.

On the front lines near Pokrovsk, Mr. Zelenskyy recently told troops, “This is our country, this is our East, and we will certainly do our utmost to keep it Ukrainian.”

But whether Ukraine is able to do that will depend less on presidential speeches than on something far more prosaic: convincing enough Ukrainians to keep fighting, even as the war grinds into its fourth year and the world’s biggest military power and Kyiv’s main backer looks for a way out.

![Scott Bessent Explains The Big Picture Everyone is Missing During the Shutdown [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Scott-Bessent-Explains-The-Big-Picture-Everyone-is-Missing-During-350x250.jpg)