Lord Ashcroft KCMG PC is an international businessman, philanthropist, author and pollster. For more information on his work, visit lordashcroft.com

The string of defections from the Conservatives to Reform has intensified both the schism on the right of politics and the debate over what to do about it.

Prosper UK, the new group launched by Sir Andy Street and Baroness Ruth Davidson, argue that the Tories should occupy the moderate centre ground. Others assert that the only way to dislodge Labour is to “unite the right” through some kind of accommodation with Reform.

Where should the Conservatives position themselves in the multiparty political landscape? Analysis of my recent polling points to some answers.

Published polling regularly shows the right’s combined vote share to be in the mid-40s – surely enough to oust Labour and install a Tory-Reform administration with a comfortable majority if only the two sets of supporters could be brought together. But even if the personalities could agree and the internal politics navigated (big enough ifs in themselves) would this hypothetical alliance be as big as the sum of its parts?

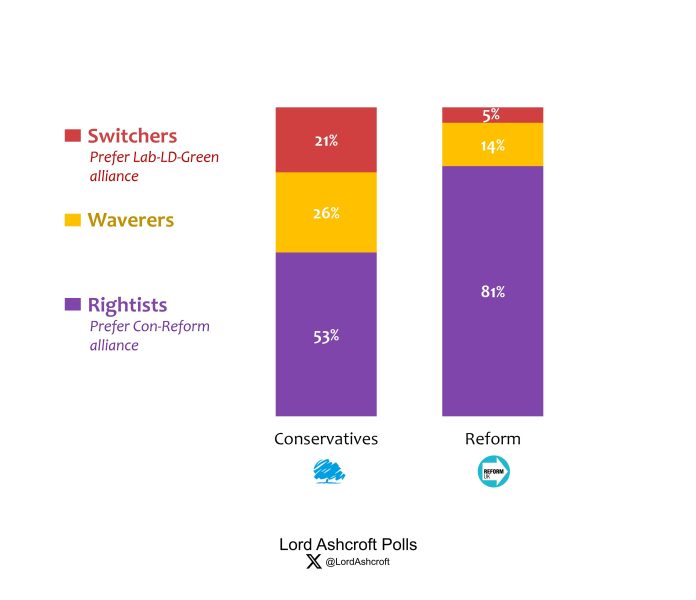

The chart below shows everyone currently intending to vote Conservative on the left and everyone currently intending to vote Reform on the right. Each party’s support is broken into three groups based upon their answers to two questions in my January poll. First, their preference between Keir Starmer and the other party’s leader (for Conservative voters, whether they would prefer Starmer or Nigel Farage as PM; for Reform voters, whether they would prefer Starmer or Kemi Badenoch). Second, the kind of government they would rather see in the event of a hung parliament at the next election – a Conservative-Reform coalition or a Labour-Lib Dem-Green coalition, or if they don’t know which they would prefer.

Within each party’s current backers, we can therefore identify three groups:

- ‘Rightists’ who prefer the other right-wing party’s leader to Starmer and prefer a coalition between Reform and the Conservatives

- ‘Switchers’ who prefer Starmer to the other right-wing party’s leader, and do not prefer a Reform-Conservative coalition in the event of a hung parliament (they either prefer a Labour-Lib Dem-Green coalition, or they don’t know)

- ‘Waverers’ who do not fall into either of the other two categories

We would expect Rightists to back a Conservative-Reform alliance at the general election, and that Switchers would not vote for such an alliance. Waverers might do either.

As we can see, the two sets of voters are far from symmetrical. While 81 per cent of current Reform voters are Rightists whom we would expect back a Tory-Reform alliance, the same is true of just 53 per cent of current Conservatives. Only 5 per cent of Reform voters would switch to back a Labour-led coalition rather than vote for an alliance with the Conservatives, but 21 per cent of current Tories would do so.

Being ahead in the polls, Reform supporters might expect to be the senior partner in such an alliance, making them more amenable to the idea. But while 91 per cent of current Reform supporters prefer Badenoch to Starmer in a forced choice, only 62 per cent of current Tories prefer Farage to Starmer.

Conservatives are much more hesitant about a pact led by their rival on the right.

If we estimate that all the Rightists, half of the Waverers and none of the Defectors would vote for a united Reform-Conservative ticket, then this ticket would achieve 36.4 per cent of the vote: 10 points lower than the current aggregate of Reform and Conservative votes. (If we were more generous and assumed that three-quarters of the waverers backed the joint ticket, this would amount to 38.7 per cent of the vote). More than two thirds of the “lost” voters – who would vote for one of the parties alone but not in an alliance with the other – would come from the Conservative side.

Of course, elections have been won with a vote share in the mid-30s: it did the trick for Tony Blair in 2005, David Cameron in 2015, and of course Starmer in 2024. Could the Reform-Conservative alliance also be elected with a share in this range? To answer this, we need to look deeper into voting intention – making use of the fact that we ask people to rate on a 0-100 scale how likely they are to back a given party. In September 2025, we asked people how likely they were to vote for each party separately, and then how they would vote if Reform and the Conservatives formed an alliance.

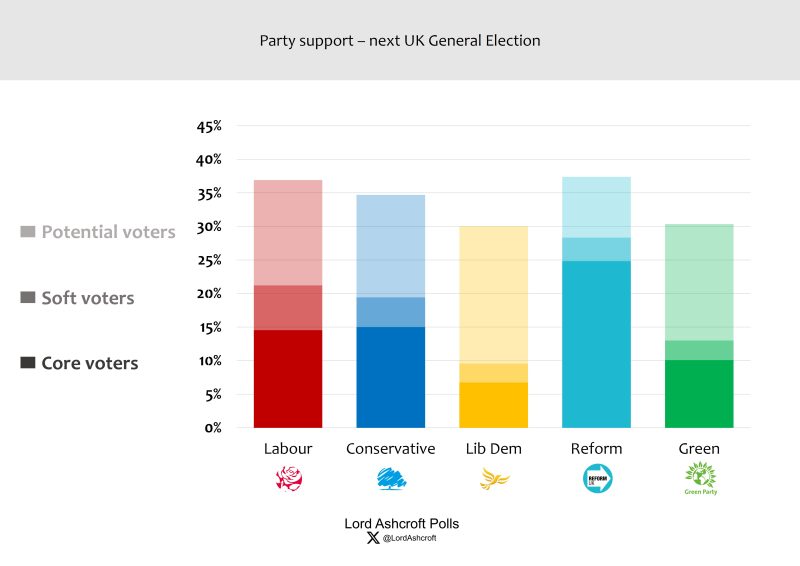

The chart below shows three categories of supporters and potential supporters for each party:

- ‘Core voters’ who intend to support this party at the next election and whose likelihood of doing so is very high (75+ out of 100)

- ‘Soft voters’ who expect to vote for this party at the next election, but whose likelihood of doing so is between 50 and 75

- ‘Potential voters’ who intend to support a different party, but are at least slightly open (25+ out of 100) to supporting this party

A party’s current voting intention is the sum of its core and soft vote. The sum of all three – Core, Soft and Potential voters – can be thought of as a party’s ceiling.

This reveals that Reform has a large and highly motivated Core vote, but on this measure currently has slightly less room for expansion than the Conservatives – even though the Tories have fewer committed supporters. But what happens if people are presented with a single combined Reform-Conservative option?

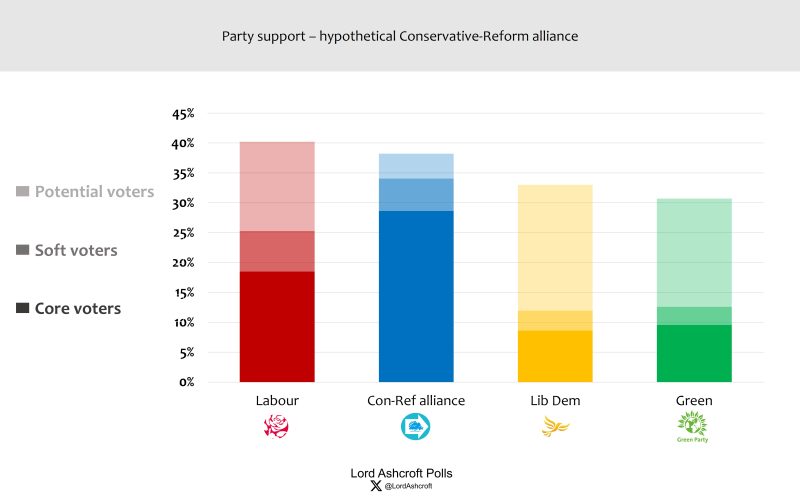

The results of this exercise reinforce the finding that a Tory-Reform alliance would shed about 10 points (in September 2025, the combined Reform and Conservative vote share was 47.6 per cent; the vote share of the hypothetical Reform-Conservative alliance was 34 per cent with a ceiling of 38.2 per cent). Crucially, it also pushes up the ceiling for Labour and the Lib Dems, suggesting that uniting the right in this way would boost tactical voting among left-of-centre voters. (Any analysis of a united right-wing vote must account for the psephological equivalent of Newton’s Third Law).

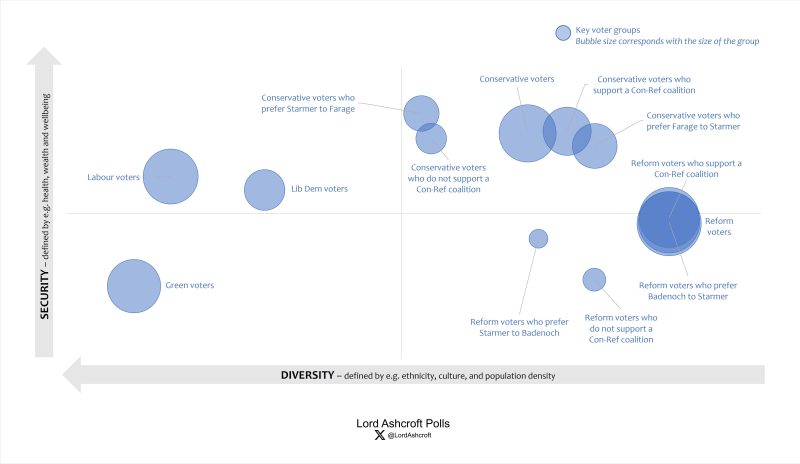

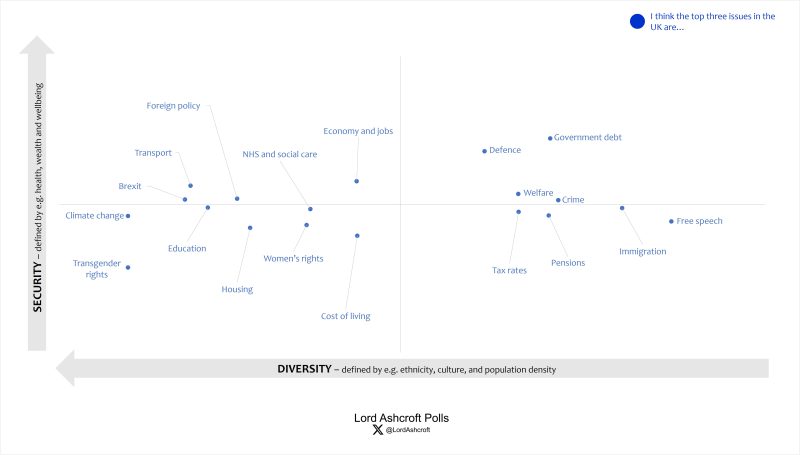

What is behind this? We can see where some of these key groups sit on our political map, which charts how views and voting behaviour varies between different parts of the electorate. The size of the group is proportional to the size of the bubble.

For a Conservative-Reform alliance to equal the sum of its parts, or come close to doing so, it would have to retain current Tories at the top and centre of the map who are closer to the Labour and Lib Dem voter bases than they are to Reform’s. At the same time, it would have to hold on to current Reform supporters around the “3 o’clock” position. In other words, it would have to bring together voters who have almost diametrically opposed views on many economic and social issues.

This is not impossible, as Boris Johnson proved in 2019. But he was helped by the unique confluence of Jeremy Corbyn and the Brexit deadlock, not to mention the Brexit Party standing down in hundreds of seats to clear the way for the Conservatives. While uniting the left has its own challenges, Labour and Lib Dem supporters occupy essentially the same space on the political map, making it much more likely that they will be willing to switch between the two. (Persuading Greens to vote Labour to stop Farage may be difficult, but if a Reform-Conservative alliance polls below 40 per cent, there is less imperative for Labour to squeeze the Greens).

Clearly, then, “uniting the right” isn’t as simple as taking the Conservative and Reform columns in current polls and adding them together. An alliance or pact between the two parties would, on current evidence, perform much worse than the sum of its parts. This would be to the disproportionate detriment of the Tories, who could potentially be destroyed as a party in the process.

What, then, should Badenoch and the Conservatives do instead? There has been no shortage of advice. Following the defections, many inside and outside the party have argued that it should not try to emulate Reform. The case has been forcefully put by Street and Davidson, who say that millions of potential Tory voters currently feel politically homeless – something I can certainly echo from my research as we listen to people up and down the country each month.

This problem would be exacerbated if the Tories were to become a watered-down version of Reform (and it would inevitably be watered down, since the insurgent party can always take the rhetoric one stage further). Voters attracted by Farage would not be tempted back, and we have seen above how embracing Reform and its agenda would hurt the Conservative party rather than consolidate overall support for the right. Many Tories are instinctively suspicious of Farage and his motives or doubt that his party could form a serious government. The fact that in 2024 the Tories lost 60 seats to the Lib Dems should also warn against a Reform-lite strategy.

But nor is the solution for the Conservatives simply to tack towards the centre ground. Some long to recreate the party of the early Cameron era – the heady (as they remember them) pre-Brexit, huskie-hugging days of the Big Society. But while the Tories cannot win without votes from centrist, liberal-minded voters, nor can it win with these votes alone. In terms of our political map, the Conservative coalition needs to begin at around the “12 o’clock” position (where we find current Tories who would rather see Starmer than Farage in No.10). But if the party moved further towards that point, it would lose ground to Reform at around “2 and 3 o’clock”, while being very unlikely to gain many compensating votes in Labour and Lib Dem territory on the left-hand side of the map. This would be especially damaging as it would leave Reform as the only party occupying the right of the political map which was once the Tories’ centre of gravity. In the battle for the right, this would amount to a Conservative retreat.

In fact, as the nostalgists should remember, this is something that Cameron himself well understood. His modernisation programme was a response to the politics of the time: the deficit and its roots in Brown-era profligacy, welfare dependency and other social problems resulting from state overreach, and an understanding of how the Conservatives were seen after their long years in office. His majority-winning electoral coalition of 2015, built on the “long-term economic plan” to restore the public finances, embraced wavering centrist voters sceptical of Labour, traditional Tories, and right-leaning Eurosceptics who were kept on board with the promise of an EU referendum.

What does this mean in practice today? Our evidence points to two pillars upon which a Conservative recovery can be built: leadership and the economy. In my January poll, in head-to-head contests where people are forced to choose without a “don’t know” option, Badenoch beat Starmer by four points, and Farage trailed Starmer by 16 points. Reform voters overwhelmingly prefer Badenoch to Starmer, but a sizeable minority of Conservatives would choose Starmer over Farage. At the same time, the Tories enjoyed a six-point lead over Labour on being trusted to manage the economy – a lead which has ticked up steadily from month to month. Taken together, these things suggest the Conservatives should pursue their focus on the economy, controlling public spending, and offering strength and stable leadership in contrast to a weak government with no sense of direction and no ability to get anything done.

There are further clues in the chart below, which shows which kinds of voters are most likely to prioritise which issues. Along with the economy, whose position close to the centre of the map shows it to be important across the board, the Conservatives have already started gaining permission to talk about the things their target voters are most concerned about.

How the Conservatives talk about these issues also matters. Britain is too expensive, taxes are too high, living standards are stuck, we are unproductive and uncompetitive, the state spends and borrows too much, the welfare bill is ballooning, our borders are not properly controlled, public services are not good enough, our defence has been hollowed out, the authorities take a selective approach to crime and ambitious young people increasingly want to leave. People are frustrated, even angry, and that needs to be articulated. But anyone can list these problems, and they do every day. It is not enough for an aspiring party of government simply to describe them and rail against them.

The Conservatives need a proper analysis and understanding of how – over successive governments – Britain got into this state. Then they need a plan, including a willingness to take robust positions that some will find uncomfortable. And they need to show that they are prepared to do the necessary work and, crucially, to be honest that there will be winners and losers from the tough decisions that will follow. Here will be the contrast not just with Labour, who after more than a dozen policy U-turns have given up any attempt at welfare reform or spending control, but with Reform, who would not even defend the two-child benefit cap.

To begin with, the Tories must stabilise, unify and continue to focus their attention primarily on the economy.

Over time, voters’ patience with the Labour government will become increasingly strained, and Reform will also come under closer scrutiny. Uncommitted voters might contrast a rigorous Conservative offering with that of an untested party with more complaints than solutions – a properly conservative way to win trust and unite the right.

You can read more at LordAshcroftPolls.com

![Florida Officer Shot Twice in the Face During Service Call; Suspect Killed [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Inmate-Escapes-Atlanta-Hospital-After-Suicide-Attempt-Steals-SUV-Handgun-350x250.jpg)