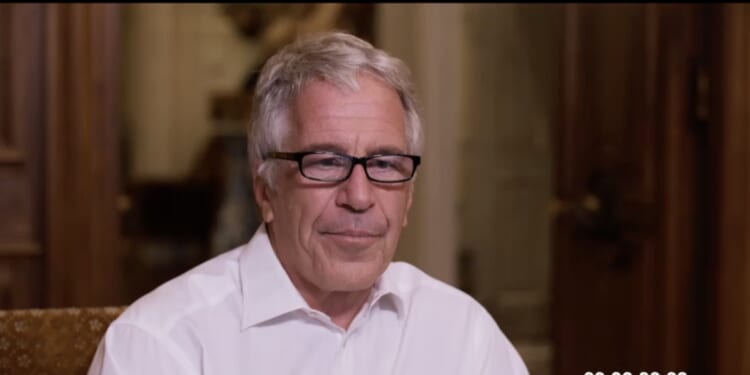

Jeffrey Epstein called himself a “hermit” in two hours of 2019 interview footage just released. This seemed strange but probably on one level accurate. Despite his name invading the news with increasing ferocity over the last two decades, Epstein’s Woody Allen-ish voice remained completely unknown to me, and perhaps to many who follow current events, until his conversation with Steve Bannon was uploaded to YouTube.

Stranger still, watching Epstein discourse on myriad topics for two hours resulted in no compulsion to immediately take a shower. Unlike with, say, Harvey Weinstein or Jimmy Savile, the mere look of Epstein did not provoke a visceral reaction of disgust. The disgust comes on an intellectual level after actively thinking about his deviance rather than on a physiognomic level while passively watching him speak.

In fact, the more Epstein talked to Bannon, the more I wanted him to talk — and for Bannon to let him. He mesmerized. A reason beyond the money and the dark pleasures of Epstein Island existed for so many people to voluntarily pursue his company. Epstein was, to use an albeit overused word, brilliant. (RELATED: A Royal Nightmare)

This superlative risks upsetting a coalition of simpletons and highbrains, who regard “smart,” “intelligent,” and “genius” as shorthand for every other positive attribute to include “righteous,” “wise,” “prudent,” “dependable,” and “good.” Tellingly, the U.S. Marine Corps includes “intelligence” nowhere in its 14 leadership traits. Other qualities matter; some more. Consider that both in literature and in life, villains often come equipped with an abundance of brains.

Professor Moriarty? Hannibal Lecter? Lex Luthor?

Theodore Kaczynski? Edmund Kemper? Heinrich Himmler?

Bannon seemed to grasp this point in asking an ostensibly silly question: Are you the devil? He pointed out that, after all, Lucifer exhibits cunning and intelligence.

This man, who invited comparisons to Mephistopheles, however, exuded the qualities stereotypically found in a more benign archetype: the high school’s star mathlete, a kid who knows pi to the hundredth decimal but cannot ask a girl to dance or befriend anyone who already has a friend. One wonders if that social awkwardness, coupled with multiple double-promotions in school, contributed to a suspended adolescence of sorts that led to that compulsion for underage girls.

Did Jeffrey Epstein think the rules did not apply to geniuses or that he was too smart to get caught?

“You’re the smartest guy in the room,” Bannon told Epstein during the interview. “You know that.” Epstein neither blushed nor corrected him. His non-expression communicated agreement. But even the smartest guy in the world, if he has any humility or even sense, begs off such praise. Epstein felt comfortable with it. This, like the mathlete awkwardness, raises questions about the origins of his dangerous predilection.

Did Jeffrey Epstein think the rules did not apply to geniuses or that he was too smart to get caught?

From the jump, Bannon asked Epstein about his initial attendance at a Trilateral Commission meeting. Epstein described it as “boring.” Really? Bannon wondered if he felt bowled over by all of the powerful people. “No, I am not wowed by people of position,” he explained. “I am wowed by people of great ideas.”

Epstein understood the men he influenced and who sought his counsel. “Many of these world leaders become world leaders,” he explained, “because they are popular.”

Surely a populist such as Bannon understands the value of popularity better than Epstein, the elitist?

Bannon, a former investment banker with Goldman Sachs, queried Epstein, a former Bear Stearns trader and limited partner, about the financial collapse of 2008. Epstein bucked conventional wisdom and laughed off derivatives as the cause.

“The real enemy of the finance system was Bill Clinton,” he explained. “If you ask me what and who caused the financial crisis, I would tell you it’s Bill Clinton.” (RELATED: Epstein Files Law Passed During Week of JFK Assassination Anniversary Seems Like a Sign)

Why? Because Clinton sold a delusion that everyone, including people habituated to angrily confronting repossession men and relying on the Visa to pay off the American Express, should own a home.

Epstein explained the semantics that transformed applicants with “good credit” to “prime” borrowers and applicants with “bad credit” to “subprime” borrowers. Our nonjudgmental society pressured a profession that required judgment for survival to cast it off. Governments indemnified these horrible loans, which in effect allowed risky cases to borrow enormous sums of money. Epstein concluded, “Politics doesn’t belong in the markets.”

The Epstein of the Bannon interview rejected magic but not miracles. He believed in souls despite their invisibility. “The soul,” he posited, “is the dark matter of the brain.”

Perhaps this sounds like fortune-cookie wisdom, and his take on world leaders and the financial collapse strikes as interesting if not wholly original. His rejection of the monomania to transform every problem into a mathematical equation to solve relied on not mere brilliance but wisdom.

Bannon, who directed the Biosphere 2 experiment during the 1990s, questioned Epstein about his involvement in the Santa Fe Institute.

Epstein exhibited less enthusiasm for his project than Bannon did for his. He described the institute’s research into complex systems as “a total failure.” Big Ideas, he seemed to say, often amount to Dumb Ideas. Bannon, who at times seemed to want to ventriloquist Epstein’s answers, refused to accept Epstein’s characterization of the fixation to quantify everything as a delusion of the intelligent.

“Men want to measure everything,” Epstein reasoned, but not everything lends itself to measurement. Mathematicians and other men of science engage in a massive category mistake in imagining their field as the Rosetta Stone of everything.

“Science doesn’t describe romance,” he noted. “I don’t know why I’m attracted to somebody.”

Epstein’s interlocutor appeared flummoxed. He called Epstein’s manner of rejecting the pleasing idea of predictability in markets if only geniuses devised the right formula, and much else, as “bull$#!+” and “happy talk.”

Here, Bannon said something about himself in attempting to say something about Epstein.

Full disclosure: I worked for Bannon — Steve to me — as an editor for a number of years at Breitbart, a publication that by the rules of truth in advertising should go by the name Bannon. In a popularity contest, Andrew Breitbart surely defeats Bannon among Breitbart employees past and present by a margin considerably wider than the outcome of a gridiron contest between Oklahoma and McNeese State. But the transformation of that successful website from a collection of bloggers and activists to a professional journalistic outfit owes more to Dark Steve than St. Andrew.

Still, his obsession with the quantity rather than the quality of articles puzzled me greatly. So, too, did his unnecessary prodding for output as though he were a corporate manager and we, the writers, the “grundoons” — a Pogo-ism he embraced from his time on Wall Street. Writers, real writers, feel a compulsion to read and write. Steve, who simultaneously texted while watching a television as he hosted his satellite radio program and likely imagined that others could multitask as he did, did not understand what drives writers (or that writing requires concentration and not chaos). While working for him, it seemed clear that Bannon, even as he oversaw the successful transformation of an upstart website into a digital juggernaut, neither understood writers nor fit as the boss of an enterprise based on writing.

This puzzled me until now. Why was a guy, who made a success of a journalistic outfit during a time when so many similar new and longstanding projects failed, ill-suited for his position? The answer remained mysterious (a quality that apparently torments Steve but remains a reality to coexist beside for those not captured by the clutches of the ideology of scientism). More importantly, the question itself seemed wrong given that Steve led Breitbart at one point, if my memory serves me right, to the 29th most visited website in the United States. Then his conversation with Epstein hit the internet, and the answer hit me. Steve is a numbers guy who simply does not grasp letters people.

Bannon could transcend his years hobnobbing among the elites to put his finger on what the people wanted as Trump’s 2016 campaign guru. Mired in a numerical swamp, he could not navigate Word World (just as so many of us inhabitants of Word World would feel lost among the digits that confuse us but comfort fellows like Steve).

Epstein, a math nerd of the first degree, nevertheless realized through the painful loss of time and treasure that this idea of attainable certainty, seductive to highly intelligent people like Steve, amounted to a fool’s errand. Equations and the scientific method and a careful study can tell us much. They cannot tell us everything.

And they cannot tell us why Jeffrey Epstein, a multimillionaire with a brain and beautiful women vying for his attention, fetishized underage girls. That, like why Steve Bannon inquired about the Trilateral Commission, the 2008 financial collapse, and Isaac Newton but not Virginia Giuffre in this conversation, remains one of those mysteries that keep life interesting.

READ MORE from Daniel J. Flynn:

Springsteen’s ‘Streets of Minneapolis’ an Ode to Fascists Obstructing the Law

![Florida Man Arrested, Said He Had a 'Dirty Bomb' in His Truck [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Florida-Man-Arrested-Said-He-Had-a-Dirty-Bomb-in-350x250.jpg)

![Keith Ellison Caught Promising to Fight State Agencies for Somali Fraudsters [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Keith-Ellison-Caught-Promising-to-Fight-State-Agencies-for-Somali-350x250.jpg)