Lord Ashcroft KCMG PC is an international businessman, philanthropist, author and pollster. For more information on his work, visit lordashcroft.com

Th following is an edited version of Lord Ashcroft’s presentation to the International Democracy Union in Brussels

Since his inauguration in January, President Trump has wasted no time implementing what supporters and opponents agree is a radical agenda, both in the United States and internationally.

My latest research looks at how his second term looks so far to different parts of his voting coalition at home, and the implications for America’s relationships with her allies, especially here in Europe. It’s also worth thinking about the elements of Trump’s appeal that our parties around the world need to respond to – such as concerns about migration, the costs of pursuing net zero and the loss of cultural self-confidence – and the risk of some of these things being tainted by the way the 47th president goes about his business.

For the US perspective I have carried out a 10,000-sample poll and 12 focus groups in Georgia, Nevada and Pennsylvania, three of the decisive states last November. Further afield, I have conducted surveys in five countries across Europe – Britain, France, Germany, Poland and Estonia – to explore how both sides of the western alliance view the transatlantic relationship and the implications of the new world order.

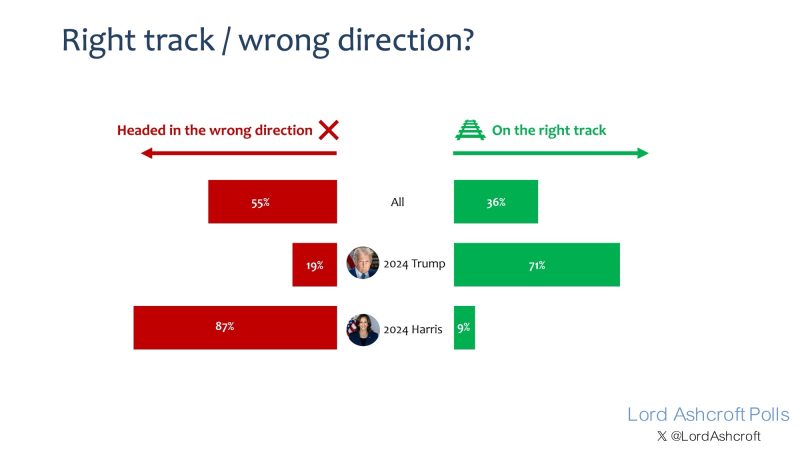

To start with the big picture, just over half of Americans now say the country is currently heading in the wrong direction. Among those who voted for Trump in November, just over 7 in 10 – or if you prefer, only just over 7 in 10 – say things are on the right track.

We found Americans overall disapproving of Trump’s performance so far by an 8-point margin. Just over half of his 2024 voters said they strongly approved, with just over a third approving somewhat. Just over 1 in 10 of them said they disapproved of his performance to date.

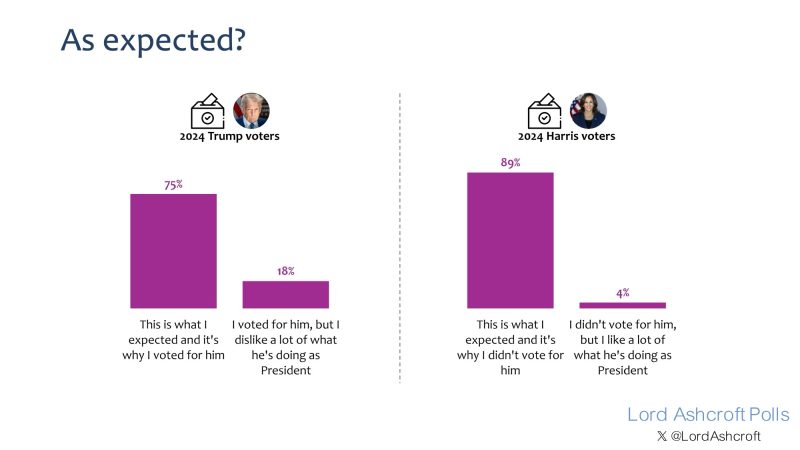

Looking back on the first 100 days leading up to our survey, three quarters of those who helped put Trump back in the White House said this was what they had expected, and it’s why they voted for him. Just under 1 in 5 Trump voters said they disliked a lot of what he was doing as president.

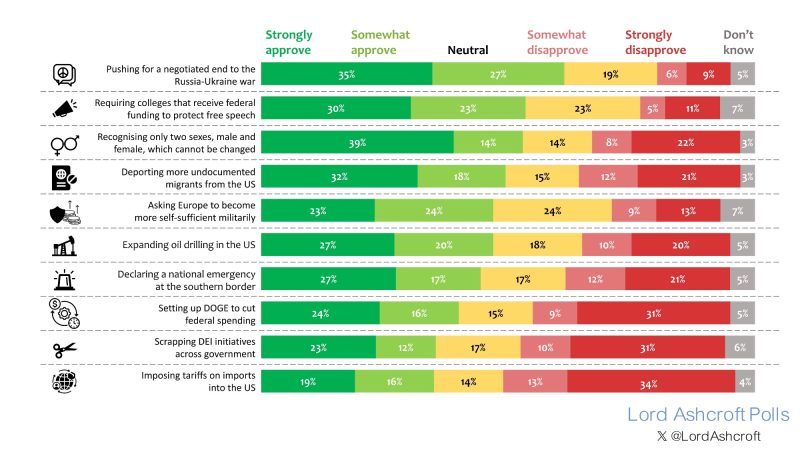

Digging deeper, we asked how strongly people approved or disapproved of some of his early actions.

Four things gained majority support across the board: pushing for a negotiated end to the Ukraine war, requiring colleges receiving federal funding to protect free speech on campus, recognising only two sexes which cannot be changed, and asking Europe to become more self-sufficient militarily. Expanding oil drilling and declaring an emergency at the southern border also had more backers than opponents. Opinion was divided on DOGE, and there was more scepticism about scrapping DEI initiatives and imposing tariffs – about which, more later.

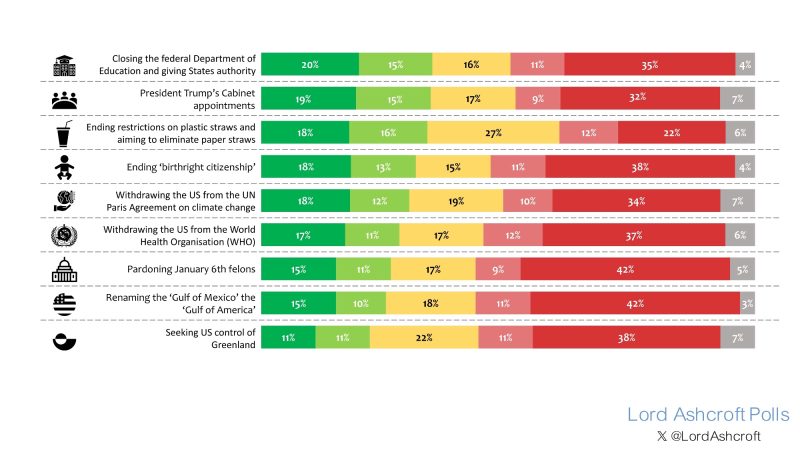

At the other end of the scale, only around 3 in 10 approved of the push to end birthright citizenship, and fewer still supported withdrawing from the Paris Agreement on climate change, leaving the World Health Organisation, pardoning the January 6th felons and trying to take control of Greenland.

Looking in more detail at the tariffs, it’s fair to say we found considerable scepticism.

Fewer than 1 in 10 voters overall – including only around 1 in 7 Trump voters – thought the tariffs had no downsides for the US. Overall, most Americans felt the downsides would outweigh the upsides, or that there were no upsides at all.

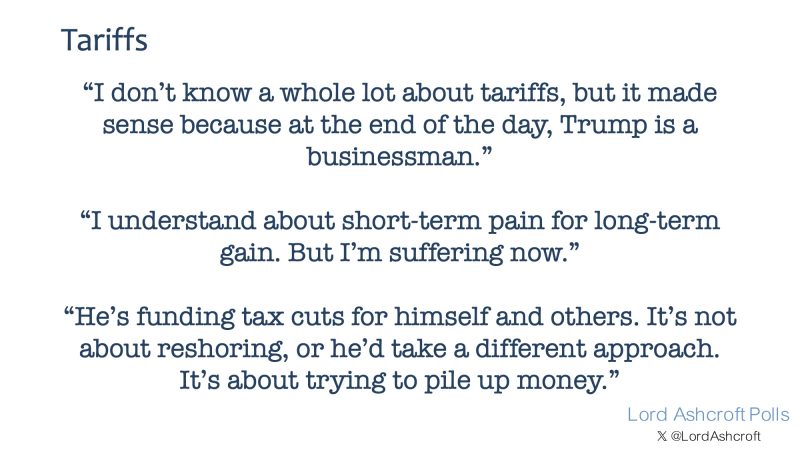

Our focus groups had various explanations of what Trump was trying to achieve with the tariffs, whether they thought they would be effective or not: a more level playing field for international trade; bringing jobs back to the US; cutting the trade deficit; making America more self-sufficient; raising revenue to cut taxes or the deficit; and tackling drug trafficking from China, Canada and Mexico.

As you can see from these verbatim quotes, some were not sure what the tariffs were for or how they were supposed to work, but felt there were things about trade and the economy that needed correcting and trusted that Trump had a plan and knew what he was doing. They tended to take it as read that the tariffs were “reciprocal” and matched what other countries charged on imports from the US.

The 90-day pause soon after the initial announcement was either considered part of Trump’s negotiating genius, or proof that he was making things up as he went along – depending on the voter’s pre-existing view of the president. Other worries, expressed by a number of Trump voters as well as opponents, were the prospect of price rises, job losses, shortages, and damage to America’s international relationships. Some noted that even if they worked on their own terms – bringing back manufacturing jobs to the US, for example – the results would take years to be felt, while they needed help now.

Another concern, mentioned in a couple of groups, was that Trump was trying to raise revenue in order to cut taxes for the highest earners. If this idea gained currency, it would obviously be politically toxic if ordinary voters end up facing higher prices or empty shelves.

We’ve seen so far that a fair chunk of the Trump vote is already doubtful at best about what they have seen of his second term so far. Scouring the data, we find the most striking differences within the Trump coalition are between those who voted for him positively, and the more reluctant “lesser of two evils” voters who were mainly trying to stop another candidate.

This latter group, who are much more likely to identify as moderate or independent, are the ones who had to overcome doubts about Trump’s character and conduct. They backed Trump, often with strong reservations, because he promised a stronger economy and higher living standards, and they were even less convinced by the alternative. They amount to around 14 per cent of Trump’s 2024 support. Without them he would not have won the Electoral College, let alone the popular vote.

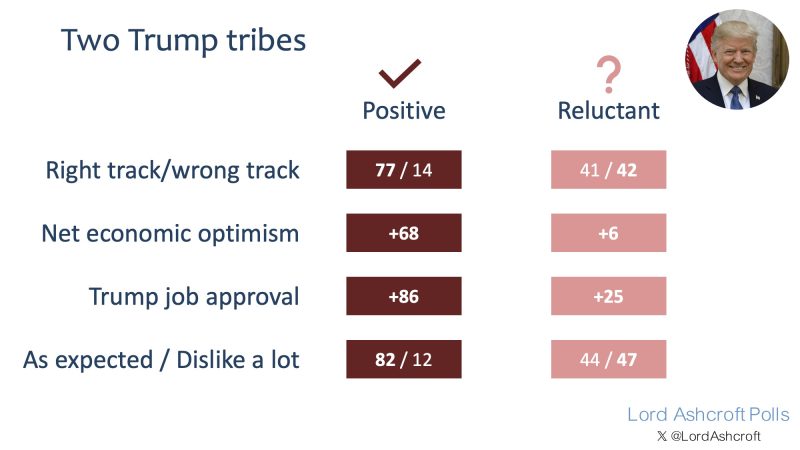

While Trump enthusiasts say America is heading in the right direction by 77 to 14 per cent, these more reluctant voters are divided. The same is true when we ask how optimistic they are for the US economy. While the enthusiasts overwhelmingly approve of Trump’s job performance, the reluctant voters are much more muted. And while the enthusiasts say the second term to date is exactly what they voted for, more reluctant Trump voters are more likely than not to say they dislike a lot of what they’ve seen so far.

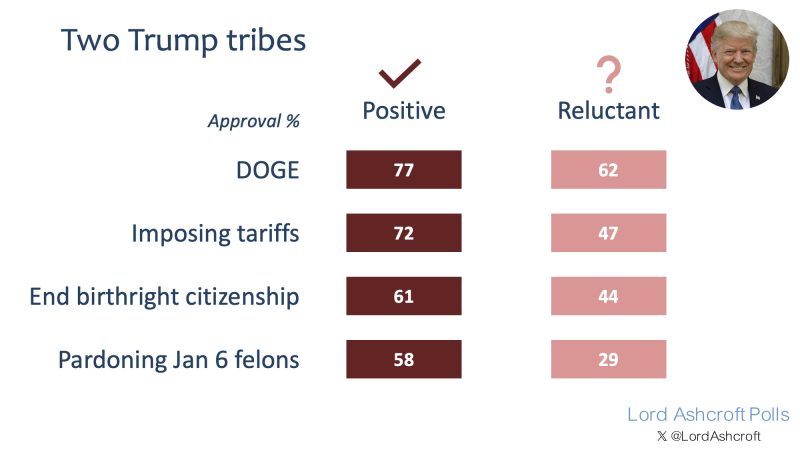

This is clear when we look at some of the specific actions listed earlier. There are areas of strong agreement, especially on border security, gender, drilling, and protecting free speech. However, just over 6 in 10 of the reluctant group back the DOGE project, compared to more than three quarters of enthusiasts. Fewer than half approve of tariffs or the push to end birthright citizenship.

The biggest gulf in opinion is on pardoning the January 6th rioters, which reluctant Trump voters oppose by a clear margin.

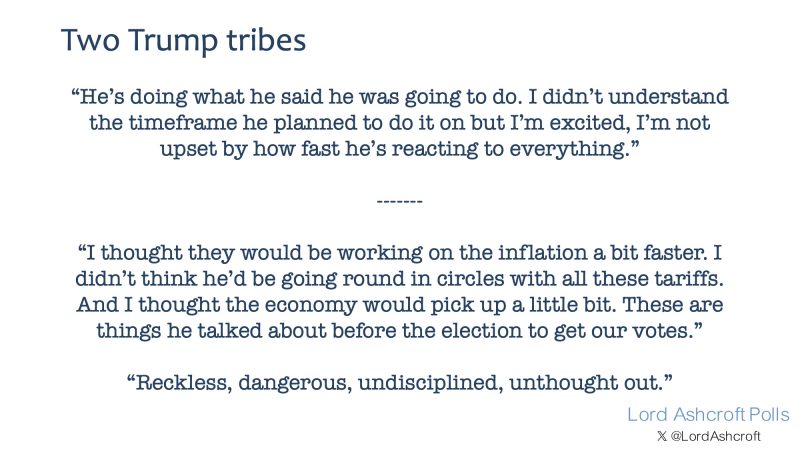

This division was also reflected in our focus groups. Enthusiasts were excited by the pace of events, enjoyed the combative approach, approved of the actions, and felt the second term to be more focused than the first and with a more loyal and cohesive team.

More reluctant Trump voters liked some of what they had seen but felt there had been a lot of chaos but little to show for it, especially on the economy and the cost of living, which were their main concerns. These people have less faith in Trump personally, less patience and – like the president himself – a transactional approach to politics. They will also determine the result of the midterm elections in 18 months. They struck a deal with Trump, and he has a limited time to deliver on it.

If reluctant Trump voters are worried about some of what they’re seeing, that goes double for many outside the United States who worry about America’s attitude to its traditional allies. We explored how voters on both sides of the Atlantic view that relationship as it evolves.

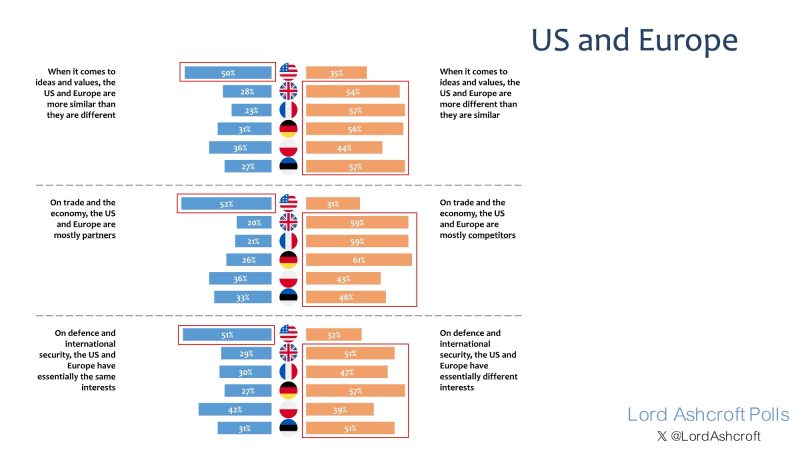

In some respects, we found European audiences more sceptical about the transatlantic alliance than Americans themselves. Americans were more likely to agree than disagree that when it comes to ideas and values, the US and Europe are more similar than they are different; in all five European countries I polled, the reverse was true. On trade and the economy, Americans are more likely than not to see Europe as partners, while most in our European countries saw the United States as a competitor. And while most Americans thought the US and Europe had essentially the same interests on defence and international security, our Europeans were more likely to disagree.

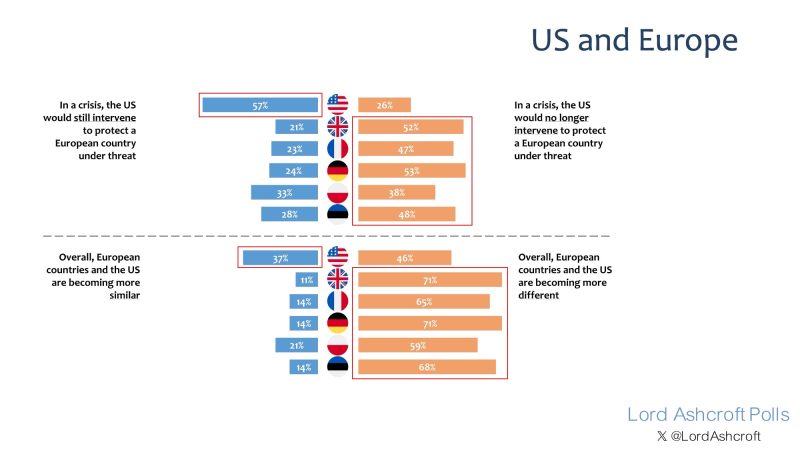

Most Americans say that in a crisis, the US would still intervene to protect a European country under threat. But Europeans are not convinced – only one third of Poles and 1 in 5 Brits think it’s true. And while Americans are more likely than not to think the US and European countries are becoming more different, Europeans themselves think so in much greater proportions.

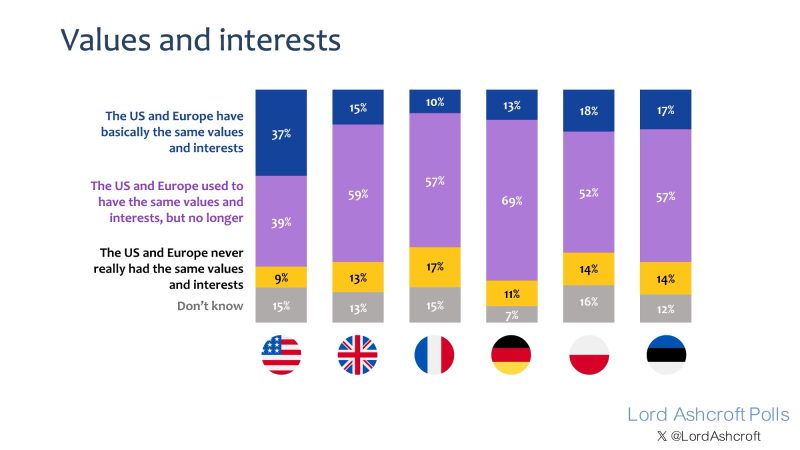

To sum it up, Americans are 3 or 4 times more likely than those in our European surveys to say that the US and Europe have basically the same values and interests. In Europe, the prevailing view was that this was once the case, but no longer.

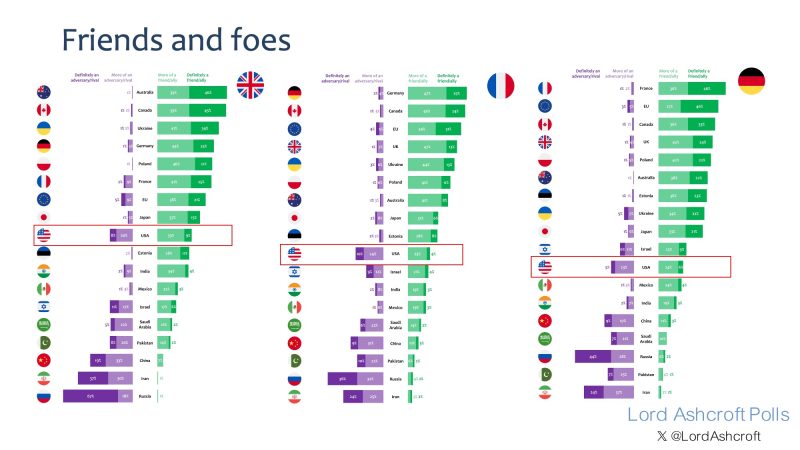

Americans saw all five of the European countries we surveyed as firm allies, and our respondents in Poland and Estonia returned the favour. But in the other three countries, the US occupied a distinctly mid-table position in their lists of friends and foes. Voters in Britain and Germany were nearly as likely – and in France, more likely – to say they saw the United States as an adversary or rival rather than a friend or ally.

It was also instructive that in a separate question, we found Americans were twice as likely as Brits, and more than four times as likely as the French and Germans, to see China as a serious threat to their security. Indeed, people in France and Germany were almost as likely to say they saw the US as a threat to their security as they were to say the same of China.

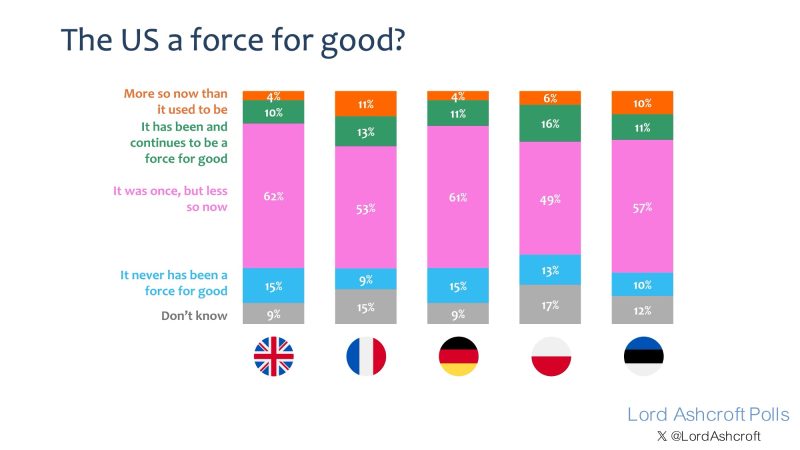

Worryingly, and I think rather sadly, populations in our European countries were doubtful as to whether the US is a force for good in the world. Again, the prevailing view in most countries – and the majority in four of them – was that the US was once a force for good, but is less so now.

Despite all this, our Europeans seem to have quite a nuanced view of where things might be heading. From their point of view, the trajectory towards a more distant relationship does not seem to be irreversible – partly because of Donald Trump’s transactional nature, partly because they separate Trump from mainstream America, and partly because of term limits.

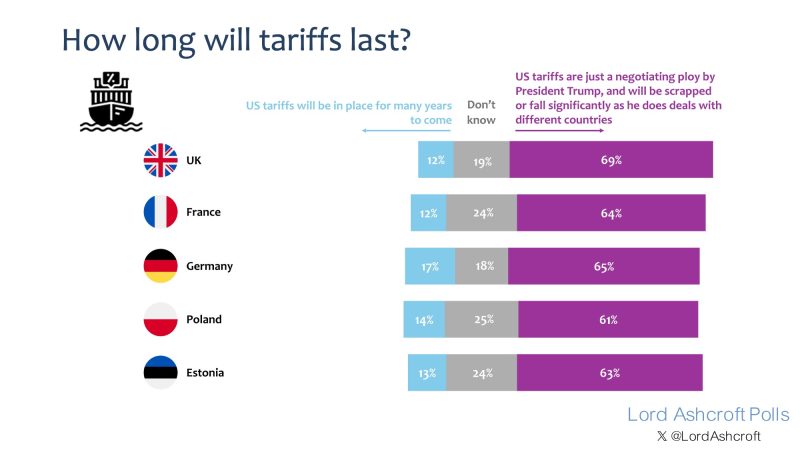

For example, large majorities in all five European countries we surveyed said they thought the tariffs were simply a negotiating ploy, and would be scrapped or fall significantly as Trump does deals with different countries around the world. The agreement with the UK struck last week would seem to encourage this view.

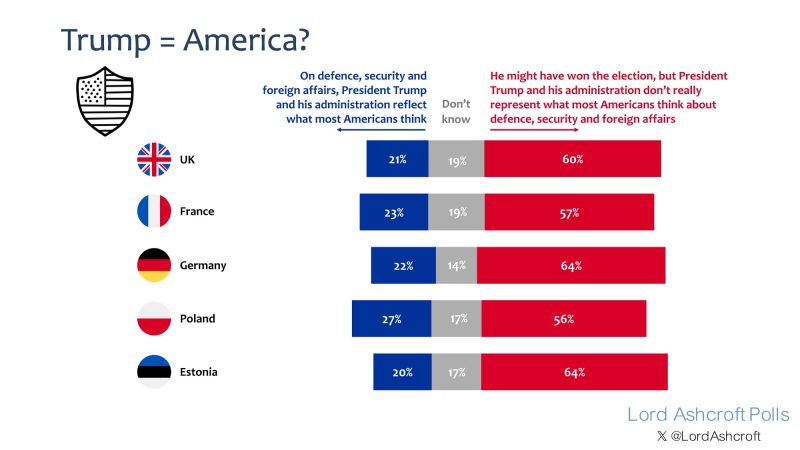

Most in our European surveys also thought that he might have won the election, but Trump and his administration did not really represent what most Americans think about defence, security and foreign affairs. Fewer than a quarter in most countries thought he really spoke for the American people on these things. I think this is rather wishful thinking, for reasons I will come on to.

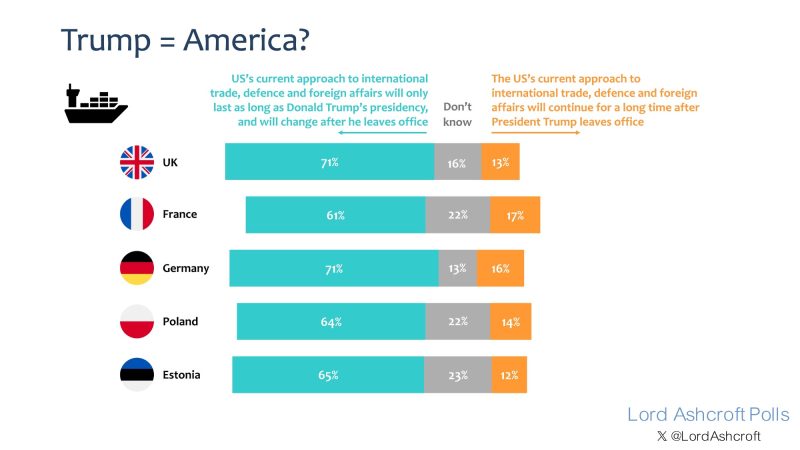

Accordingly, and also I think wishfully, only small minorities in each of our European countries believe America’s current approach to trade, defence and foreign affairs will continue for a long time after the end of Trump’s second term. Upwards of two thirds say they expect things to change once he leaves office.

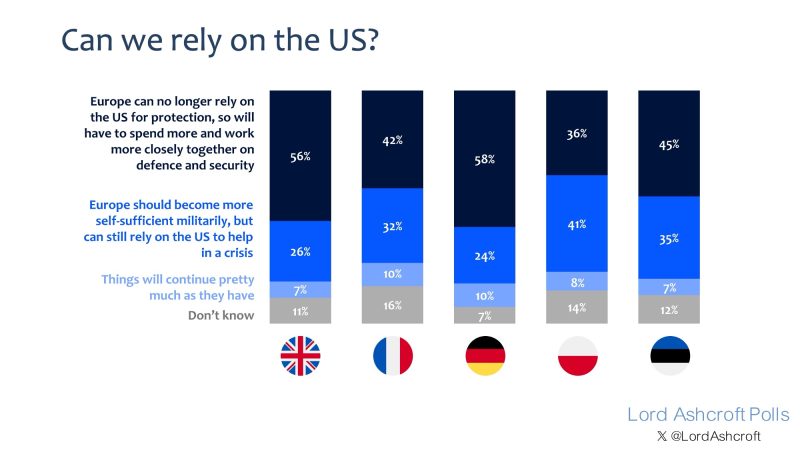

Even so, very few think things will continue as they have in recent decades. Majorities in Britain and Germany, and just under half in France and Estonia, agreed that Europe could no longer rely on the US for protection and would have to spend more and work more closely together on defence and security. Even in Poland, where people were more likely to believe the US would help in a crisis, there was agreement that Europe would have to become more militarily self-sufficient.

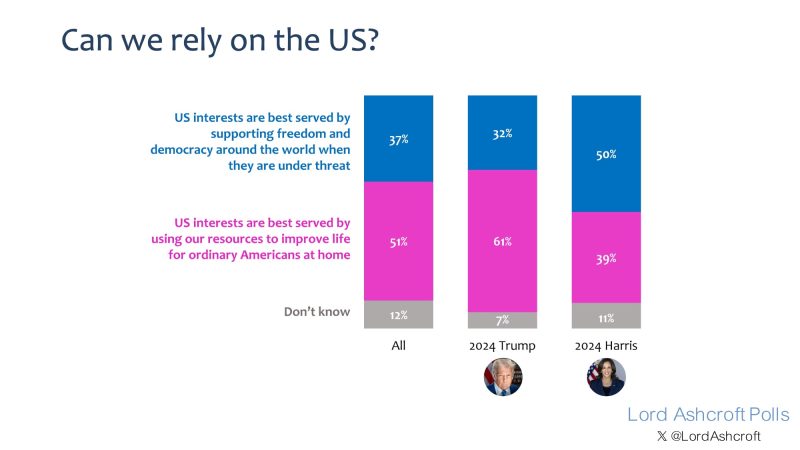

Why do I think it’s wishful thinking to believe the Trump approach to international relations will last only as long as his presidency? One reason is that Americans are significantly more likely to think their interests are best served by using their resources to improve life at home than by supporting freedom and democracy around the world. It is not so much that they are opposed to these things – rather that they feel they have carried too much of the burden for too long.

The other is that this view is by no means confined to Trump enthusiasts.

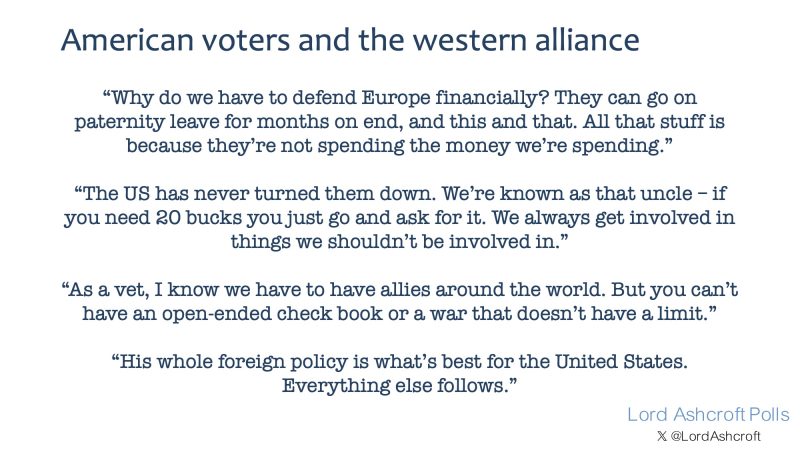

Few others are impressed with renaming the Gulf of Mexico or the pursuit of Greenland, and reluctant Trump voters are less keen on withdrawing from international organisations and treaties. However, there is majority support for pursuing a negotiated end to the Ukraine war, general agreement that American resources are needed at home, and widespread agreement across the board that Europe should take more responsibility for its own defence – as illustrated by these focus group quotes from around the US.

I think the idea that Europe is able to enjoy lavish social welfare not available in the US because the Americans pay for their defence is particularly striking.

The upshot is that no Republican candidate is going to run successfully on turning back the clock and repudiating ‘America First,’ even if those are not the words they use. And given that the section of Trump voters who will be in play at the next election tend to agree with him on these things, I would not expect to see a successful Democrat talking about ‘global America’ either.

To conclude, as well as policy challenges in defence and international trade, as I hinted at the beginning, all of this sets a political test for the parties represented in this room.

For most of my political lifetime, patriotism and national interest have largely been the preserve of the centre-right. This is no longer the case.

The Trumpian view of American nationalism has prompted a response in which the centre-left can see the possibilities in what we might call “progressive patriotism”. As well as the European attitudes I’ve described, we saw it in action last month in Canada and this month in Australia, and there are elements emerging on the left in the UK. The left will try to define themselves as a bulwark against the Trumpian menace. The challenge for us will be to define our robust view of the enlightened national interest in a way that keeps us distinct from the less popular parts of the Trump approach.

Voters will no longer be choosing between globalism and national interest, but which kind of nationalism – or which kind of patriotism – they prefer.

![Trump Posts Hilarious Pope Meme, Leftists Immediately Melt Down [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Trump-Posts-Hilarious-Pope-Meme-Leftists-Immediately-Melt-Down-WATCH-350x250.jpg)

![Bessent Exposes Media Lies About April’s Stock Market Performance [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Bessent-Exposes-Media-Lies-About-Aprils-Stock-Market-Performance-WATCH-350x250.jpg)

![Taylor Swift Slams Subpoena in Blake Lively’s Explosive Legal Battle [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/1746936931_Taylor-Swift-Slams-Subpoena-in-Blake-Livelys-Explosive-Legal-Battle-350x250.jpg)

![Wild Road Rage Brawl Erupts in Milwaukee [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Road-Rage-Turns-Violent-in-Oregon-Minivan-Mows-Down-Motorcyclist-350x250.jpg)

![Eric Adams Pushes Back on Schumer’s Coast Guard Cutback Claims After Brooklyn Bridge Tragedy [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Eric-Adams-Pushes-Back-on-Schumers-Coast-Guard-Cutback-Claims-350x250.jpg)