There’s a man who stands just outside the playground where I take my daughters on Sundays.

He doesn’t speak. Doesn’t move much. Doesn’t have children. But he’s there — same spot, same hour — leaning quietly against the fence.

He isn’t doing anything wrong. But something’s off. Not overtly. Not enough to call out. Just enough to notice. He doesn’t fit — not in any way you can articulate, but in the way your instincts catch before your mind does. And so you watch him. And pretend you’re not.

Because nothing invites more discomfort in modern life than pointing out what everyone else is trying not to see.

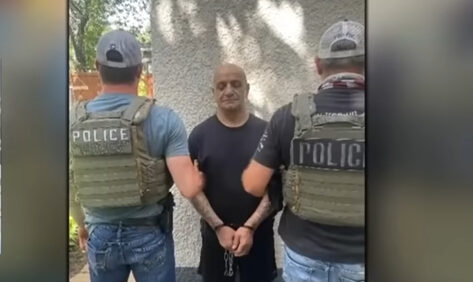

This week, the United States had its version of that man, not in a playground, but in cities across eight states. That’s where federal agents arrested 11 Iranian nationals in a coordinated ICE operation between June 22 and 24. These weren’t quiet workers or asylum seekers. They were men with suspected or known ties to Hezbollah and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), Iran’s military-intelligence arm. And they had already embedded themselves into American neighborhoods.

In Alabama, agents arrested Ribvar Karimi, a former IRGC sniper, found with Iranian military credentials. In Minnesota, Mehran Makari Saheli — a Hezbollah-linked facilitator with a prior weapons conviction and a standing deportation order — was picked up after years underground. In Mississippi, Yousef Mehridehno, flagged on federal terror watchlists after committing marriage fraud to obtain a green card, was quietly living outside Jackson. Others were apprehended in California, Colorado, New York, and Texas, on charges ranging from firearms possession to grand larceny. None were stopped at the border. All had been processed. Released. Forgotten. (RELATED: A Texas City’s Quiet Claim to Islamic Territory)

This wasn’t prevention. It was post-facto luck.

Between 2021 and 2024, over 1,500 Iranian nationals crossed illegally into the United States. At least 729 were released into the interior, the majority of them adult men, many without verifiable documents. These individuals came from a regime that funds terror groups, targets U.S. officials abroad, and carries out assassinations through proxies. Yet our system issued them court dates years into the future, handed out intake numbers, and hoped for the best.

They didn’t sneak in under the cover of darkness. They walked through — some with smiles, some with scripts, almost all with stories tailored to trigger release.

And yes, many of the Iranians showing up at the border are genuine refugees: dissidents, women escaping oppression, opposition voices fleeing the Ayatollah’s reach. But among them are also regime men —facilitators, functionaries, enforcers. And in a system allergic to scrutiny, we no longer know how to tell the difference. Can we afford to get it wrong? The obvious answer is no. (RELATED: Unseen, Unchecked, Unsafe — America’s Visa Overstay Problem)

Canada is confronting its own reckoning. The Canada Border Services Agency is now reviewing at least 66 cases of suspected Iranian regime officials who may have entered the country through standard immigration pathways. Twenty have already been ruled inadmissible. Some were deported. Most weren’t flagged by intelligence — they were uncovered by journalists. If Canada can miss high-level actors in a trickle, what might the U.S. be absorbing in a flood? (RELATED: Immigration, Islamism, and Antisemitism in Canada)

Europe offers an even darker warning. According to the International Centre for Counter-Terrorism, Iran’s security services now outsource targeted operations to criminal gangs across the continent. In January 2024, a grenade was discovered at the Israeli embassy in Stockholm, traced back to the Foxtrot gang, acting under Iranian instruction. A few months later, a 14-year-old tied to the Rumba network opened fire outside the same building. (RELATED: The Scandinavian Lesson: What Malmö Warns Us About America’s Sanctuary Cities)

In Brussels, another Foxtrot-linked operative hurled grenades at embassy personnel. In Germany, the IRGC recruited Ramin Yektaparast, a fugitive Hell’s Angels boss and dual German-Iranian national, to orchestrate planned synagogue attacks in Bochum and Essen. These weren’t isolated thugs. They were subcontracted proxies in a quiet transnational war. (RELATED: The Outbreak of Migrant-Related Crime and Rape in the EU)

The Trump administration has moved to reassert control, recently authorizing National Defense Areas along stretches of the Texas and Arizona borders. These zones allow military units to detain trespassers and offer emergency support where Border Patrol has been overwhelmed. It’s a necessary step. But it won’t fix what’s broken — a vetting system that’s lost its will to say no.

Because here is the hard truth: we do not know where the other 729 Iranian nationals are today. No biometric alerts. No central tracking. No unified intelligence protocol. Just a clipboard, a file number, and a hope that nothing happens.

Just like the man at the playground — not close enough to confront, not far enough to ignore. Present, still, and wrong in a way no one wants to name.

The question isn’t whether he belongs.

It’s whether we’ll ask — before we no longer can.

READ MORE from Kevin Cohen:

The Travel Ban Policy Overhaul

Unseen, Unchecked, Unsafe — America’s Visa Overstay Problem

How China Is Quietly Outsmarting the West

![Man Arrested After Screaming at Senators During Big Beautiful Bill Debate [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Man-Arrested-After-Screaming-at-Senators-During-Big-Beautiful-Bill-350x250.jpg)