Lord Ashcroft KCMG PC is an international businessman, philanthropist, author and pollster. For more information on his work, visit lordashcroft.com

My latest poll asked voters to assess Labour’s first year in office, whether they are happy with their 2024 vote, how long they are prepared to give Starmer the benefit of the doubt, what they think about Iran and defence spending, and Nigel Farage and Reform’s new non-dom policy. We also look at which voters have moved since the general election, and in which directions.

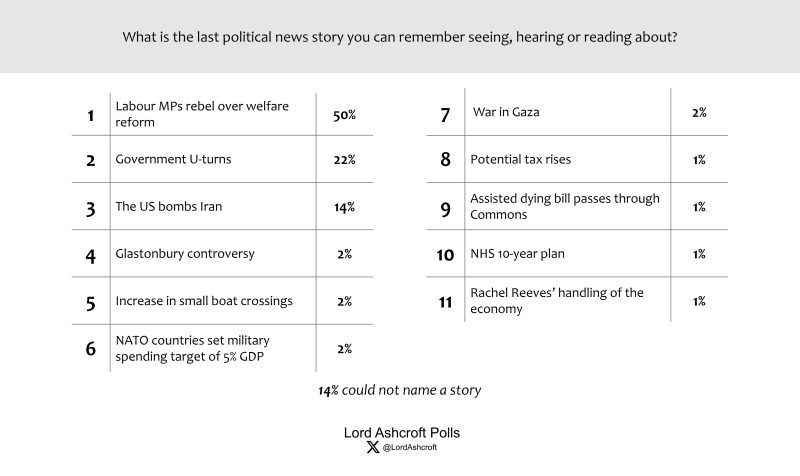

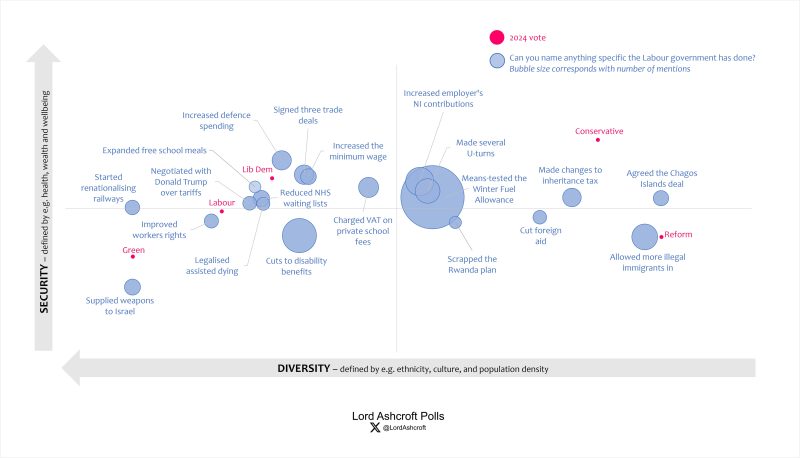

What have people noticed – and who has noticed what?

Labour’s welfare rebellion was by far the most noticed political story, mentioned by half of all our poll respondents. This was followed by a general impression of government U-turns, and the US strikes on Iran’s nuclear facilities.

Labour’s welfare rebellion was by far the most noticed political story, mentioned by half of all our poll respondents. This was followed by a general impression of government U-turns, and the US strikes on Iran’s nuclear facilities.

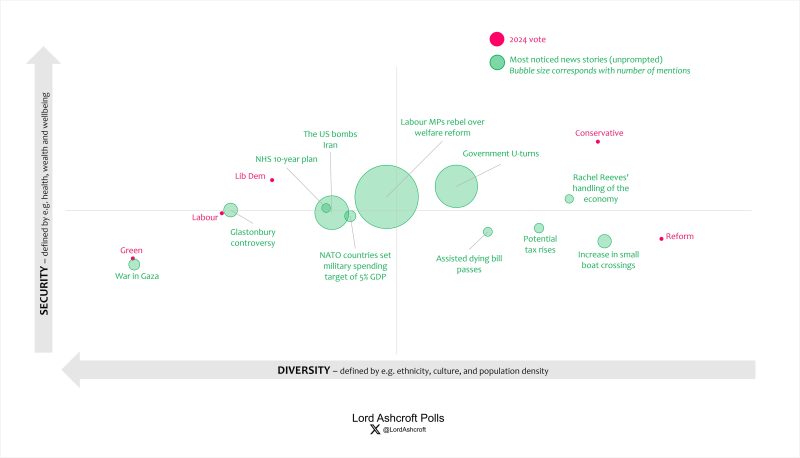

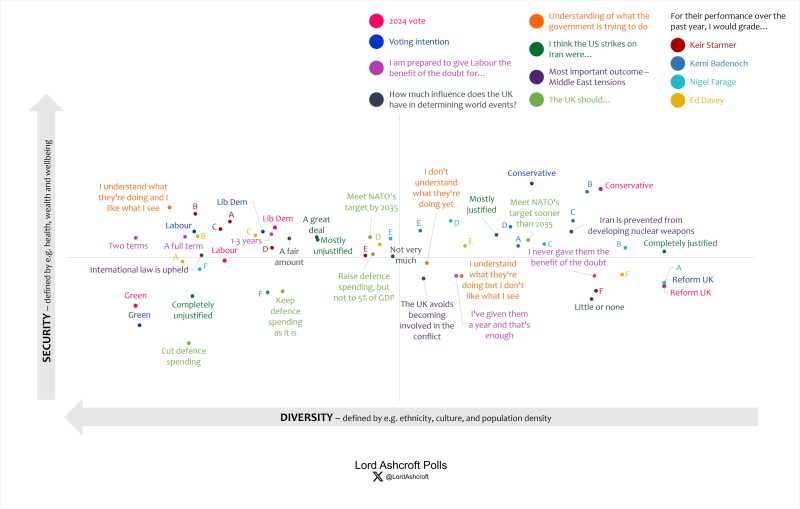

Our political map shows which stories were most likely to have been noticed by which kinds of voters. The Labour welfare rebellion appears in the middle of the map, showing it registered across the board rather than with any particular part of the electorate. Stories about the Rachel Reeves and the economy, tax rises and small boats were more likely to be recalled in Conservative or Reform-leaning territory, while stories about Glastonbury, Iran, Gaza and the NHS were most likely to be mentioned by those in left-leaning parts of the map.

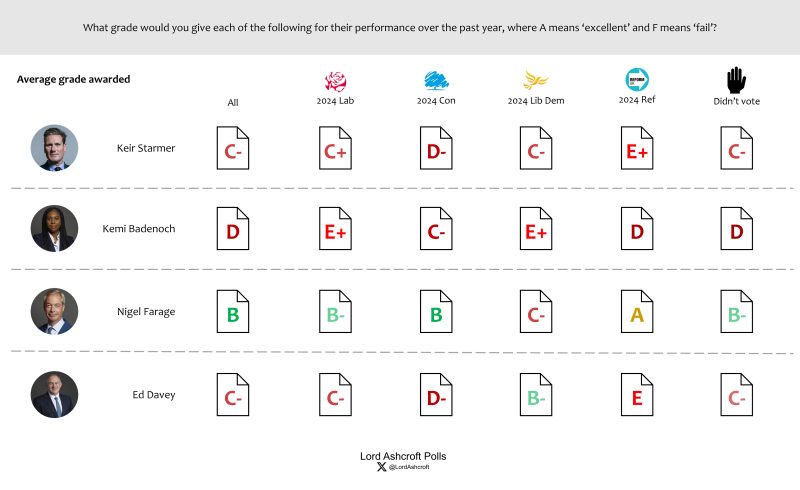

Grades for the year

When we asked respondents to give the party leaders a grade for their performance over the year since the general election, Keir Starmer received an ‘F’ from 39 per cent, Kemi Badenoch from 32 per cent, Nigel Farage from 40 per cent, and Ed Davey from 20 per cent.

Among those awarding passing grades, Nigel Farage scored highest – his average grade was a ‘B’ among voters as a whole and an ‘A’ from those who voted Reform UK in 2024 (making him the only leader to score an ‘A’ from his own supporters). Keir Starmer scored a ‘C–’ average among voters as a whole and a ‘C+’ from 2024 Labour voters. Ed Davey also scored a ‘C–’ average, and a ‘B–’ from 2024 Lib Dems. Kemi Badenoch’s average grade was a ‘D’ from voters as a wh0le, and a ‘C–’ from 2024 Tories (who awarded Nigel Farage a ‘B’).

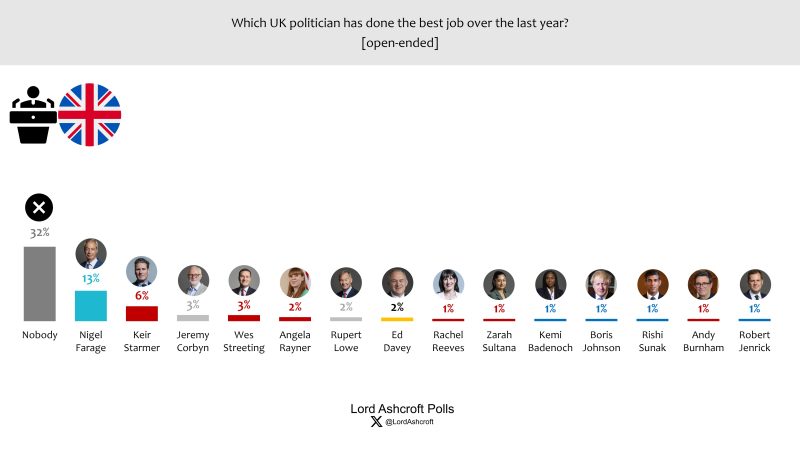

Politicians of the Year

When we asked which UK politician had done the best job over the last year, Nigel Farage was named by 13 per cent, putting him at the top of the table. Keir Starmer was in second place with 6 per cent, ahead of Jeremy Corbyn, Wes Streeting and Angela Rayner. Nearly one third (32 per cent) said no-one was deserving of the title.

We also asked which politician around the world had done the best job over the last year. Donald Trump topped the table with 12 per cent, narrowly ahead of Ukraine’s Volodymyr Zelensky and Canada’s Mark Carney.

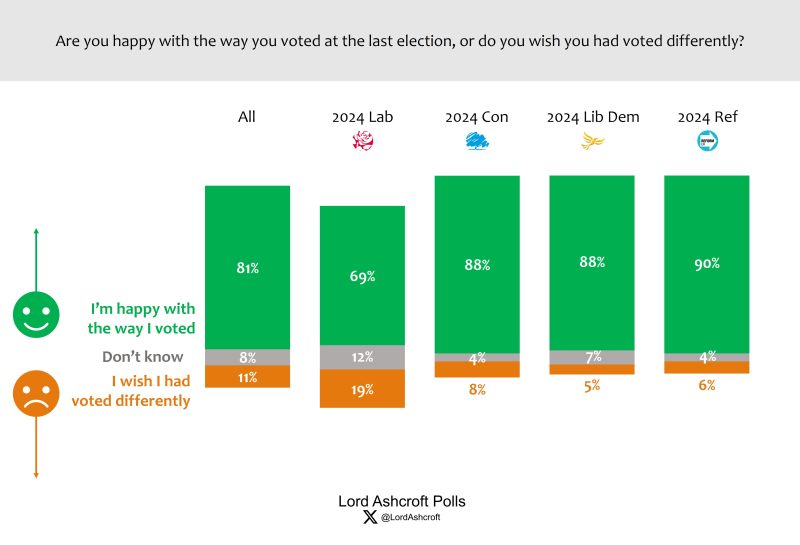

Vote regrets?

Around nine in ten of those who voted Conservative, Lib Dem or Reform said they were happy with how they voted at the 2024 general election. This fell to 69 per cent among those who voted Labour; nearly one in five said they wish they had voted differently, including a third of those who had switched from the Conservatives.

Around nine in ten of those who voted Conservative, Lib Dem or Reform said they were happy with how they voted at the 2024 general election. This fell to 69 per cent among those who voted Labour; nearly one in five said they wish they had voted differently, including a third of those who had switched from the Conservatives.

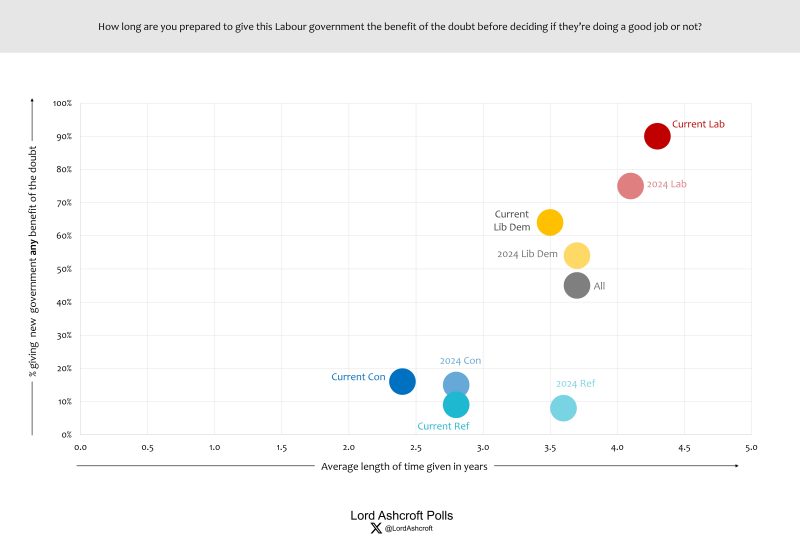

Benefit of the doubt?

When we asked people how long they were prepared to give the government the benefit of the doubt, more than half (55 per cent) said they did not do so at all – more than twice the number since we first asked in August 2024 (28 per cent). The average time of any benefit given has gone up from 3.4 to 3.7 years as others begin to fall away, but this varies widely between groups: from more than 4 years among current Labour leaners to less than 2.5 years among current Conservative leaners.

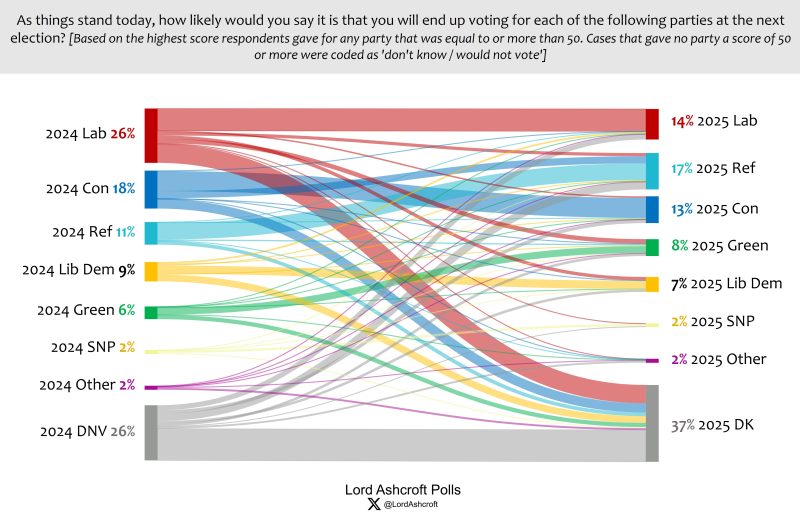

Who has gone where?

Tracing how 2024 voters have shifted allegiance over the year since the election, several things are notable. The biggest single shift is 2024 Labour voters moving to ‘don’t know’. Labour are losing around twice as many voters to the Lib Dems and the Greens combined as they are to Reform UK. Meanwhile, Reform are picking up almost as many votes from those who say they did not vote in 2024 as they are from Labour and the Conservatives – while the Conservatives are losing at least as many to ‘don’t know’ as they are to Reform.

Tracing how 2024 voters have shifted allegiance over the year since the election, several things are notable. The biggest single shift is 2024 Labour voters moving to ‘don’t know’. Labour are losing around twice as many voters to the Lib Dems and the Greens combined as they are to Reform UK. Meanwhile, Reform are picking up almost as many votes from those who say they did not vote in 2024 as they are from Labour and the Conservatives – while the Conservatives are losing at least as many to ‘don’t know’ as they are to Reform.

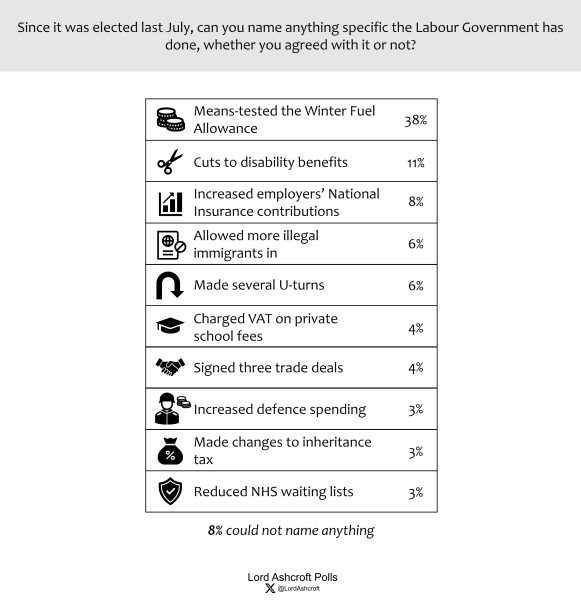

What has Labour done?

Means testing the winter fuel allowance continues to top the table when we ask people to name something specific the Labour government has done since the election. Benefit cuts, the National Insurance increase, illegal migrants and U-turns complete the top five.

Means testing the winter fuel allowance continues to top the table when we ask people to name something specific the Labour government has done since the election. Benefit cuts, the National Insurance increase, illegal migrants and U-turns complete the top five.

Our map shows that means-testing the winter fuel allowance, increasing employers’ National Insurance and making U-turns all appear close to the centre, meaning recall of these things was not confined to any particular part of the electorate. Inheritance tax, illegal migrants and the Chagos Islands were more likely to be mentioned in the Conservative- or Reform-leaning right-hand quadrants, while proposed disability benefit cuts, trade deals, defence spending and workers’ rights were most likely to be recalled in left-leaning territory.

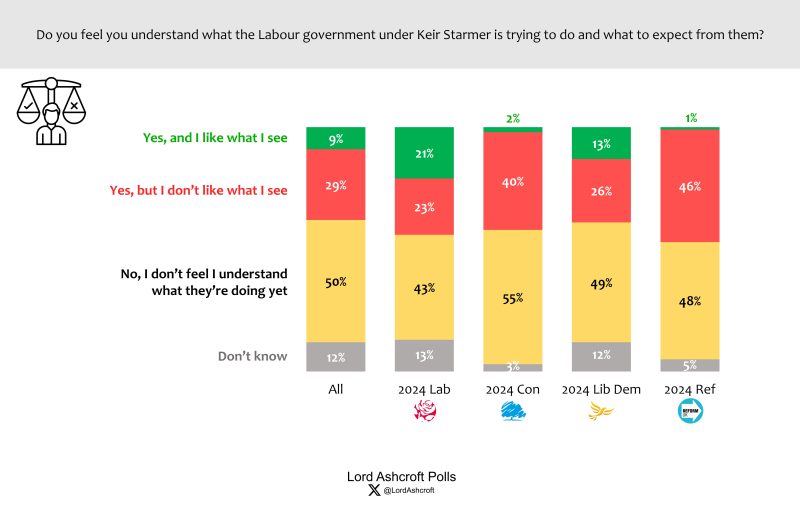

What is Labour trying to do?

Fewer than 1 in 10 of all voters said they thought they understood what the Labour government was trying to do and they liked what they saw. A further 29 per cent said they felt they understood but didn’t like what they saw. Half of all voters said they didn’t feel they understood what the government was trying to do. 2024 Labour voters were nearly as likely to say they didn’t like what they saw (21 per cent) as to say that they did (23 per cent). 43 per cent of them said they didn’t feel they understood what the government was trying to do.

Fewer than 1 in 10 of all voters said they thought they understood what the Labour government was trying to do and they liked what they saw. A further 29 per cent said they felt they understood but didn’t like what they saw. Half of all voters said they didn’t feel they understood what the government was trying to do. 2024 Labour voters were nearly as likely to say they didn’t like what they saw (21 per cent) as to say that they did (23 per cent). 43 per cent of them said they didn’t feel they understood what the government was trying to do.

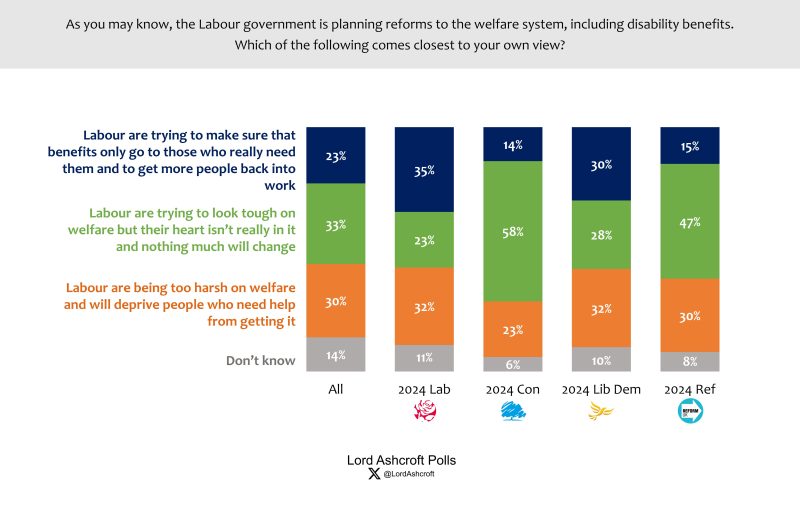

Labour and welfare

Though the question was asked and answered before the full extent of the government’s U-turn had become clear, most voters were doubtful about their plans for welfare reform.

Fewer than a quarter of voters, including just 35 per cent of 2024 Labour voters, thought Labour were trying to get people back into work and make sure benefits only go to those who really need them. Nearly one third of Labour voters, as well as more than half of Green and SNP voters, thought Labour were being too harsh and would deprive people who really need help from getting it. One third of voters overall, including a majority of Conservatives and just under half of Reform UK voters, thought the government were trying to look tough on welfare but Labour’s heart wasn’t really in it and nothing much would change.

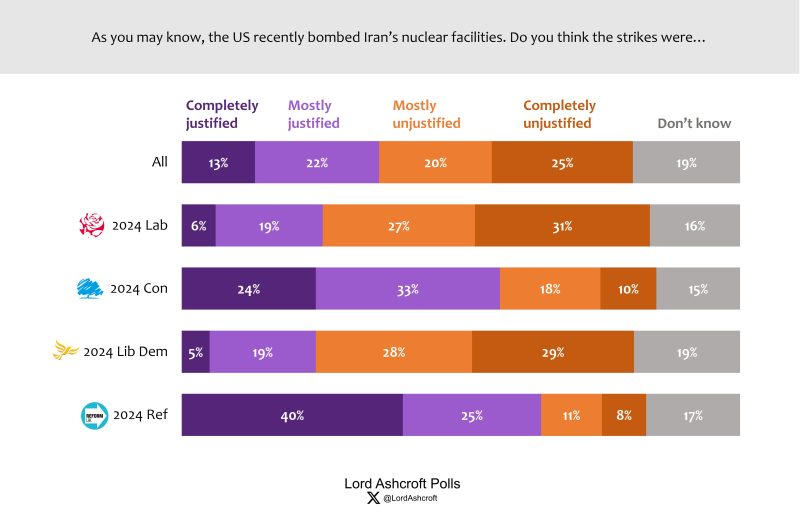

Iran, defence and Britain’s influence

While majorities of 2024 Conservative and Reform UK voters said the strikes on Iran’s nuclear facilities were justified, Labour, Lib Dem and (especially) Green voters were opposed, and voters overall felt they were unjustified by 45 per cent to 35 per cent.

While majorities of 2024 Conservative and Reform UK voters said the strikes on Iran’s nuclear facilities were justified, Labour, Lib Dem and (especially) Green voters were opposed, and voters overall felt they were unjustified by 45 per cent to 35 per cent.

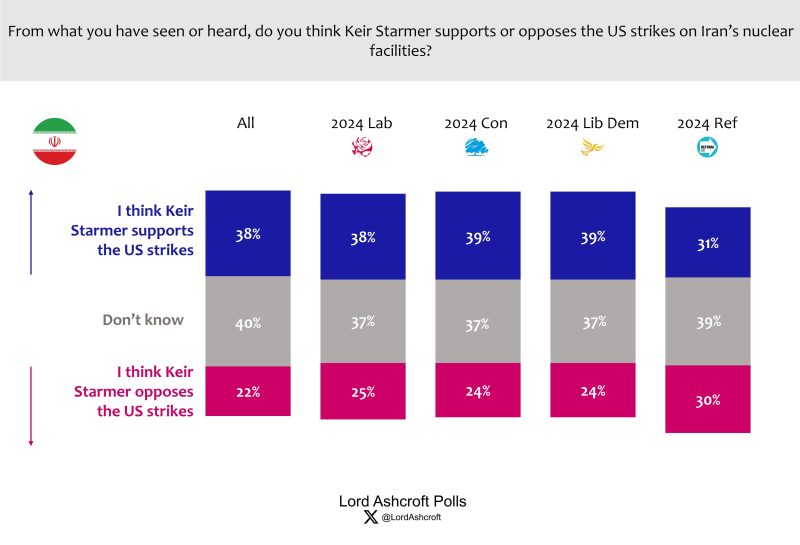

Four in ten said they didn’t know whether Keir Starmer supported or opposed the strikes on Iran’s nuclear facilities. Of the remainder, voters were more likely to think he supported them (38 per cent) than opposed them (22 per cent), with little variation between different parties’ supporters.

Four in ten said they didn’t know whether Keir Starmer supported or opposed the strikes on Iran’s nuclear facilities. Of the remainder, voters were more likely to think he supported them (38 per cent) than opposed them (22 per cent), with little variation between different parties’ supporters.

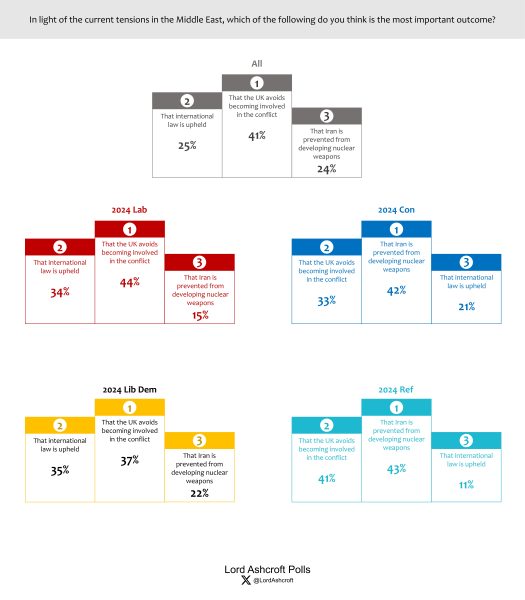

A plurality of Conservative and Reform voters said the most important outcome was that Iran was prevented from developing nuclear weapons. For Labour and Lib Dem voters, the priority was for the UK to avoid becoming involved in the conflict (though for Lib Dems it was nearly as important that international law be upheld).

A plurality of Conservative and Reform voters said the most important outcome was that Iran was prevented from developing nuclear weapons. For Labour and Lib Dem voters, the priority was for the UK to avoid becoming involved in the conflict (though for Lib Dems it was nearly as important that international law be upheld).

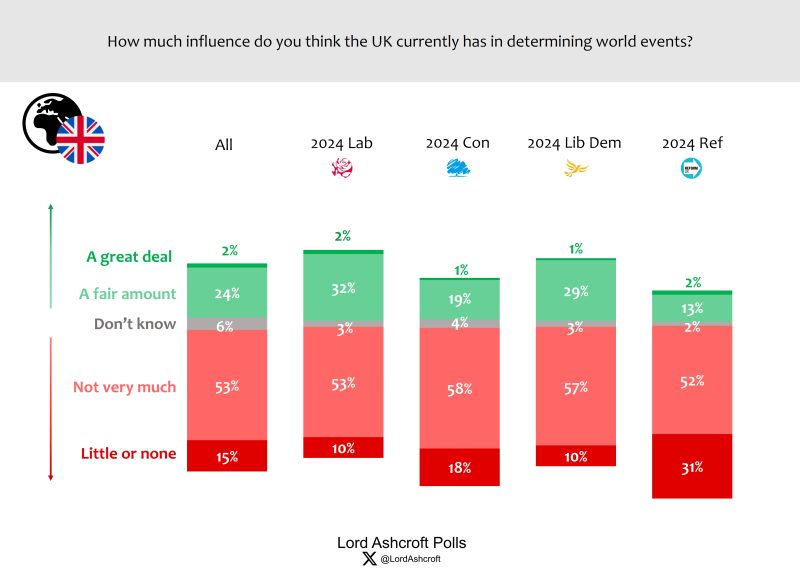

Only one in fifty voters said they thought the UK currently has a great deal of influence in determining world events, while just under a quarter thought we had a fair amount of influence. 2024 Labour voters were the most likely to think the UK had a great deal or a fair amount of influence, with 2024 Reform UK voters the least likely to think so.

Only one in fifty voters said they thought the UK currently has a great deal of influence in determining world events, while just under a quarter thought we had a fair amount of influence. 2024 Labour voters were the most likely to think the UK had a great deal or a fair amount of influence, with 2024 Reform UK voters the least likely to think so.

Majorities of all parties’ voters – and nearly seven in ten overall thought the UK currently had either not very much, or little or no influence on world events.

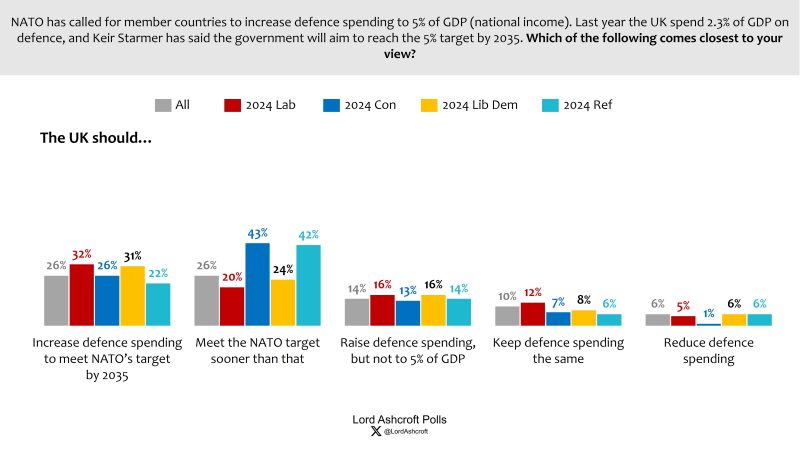

A majority of voters wanted the UK to meet the new NATO target of spending 5 per cent of GDP on defence either by 2035 as promised by Keir Starmer (26 per cent) or sooner than that (also 26 per cent). Conservative and Reform UK voters were more likely to support the target and more eager to meet it sooner than 2035. Only a minority of Green and SNP voters supported raising defence spending to the NATO target, with 36 per cent and 28 per cent respectively thinking the UK should cut defence spending or keep it at its current level.

Farage and the non-doms

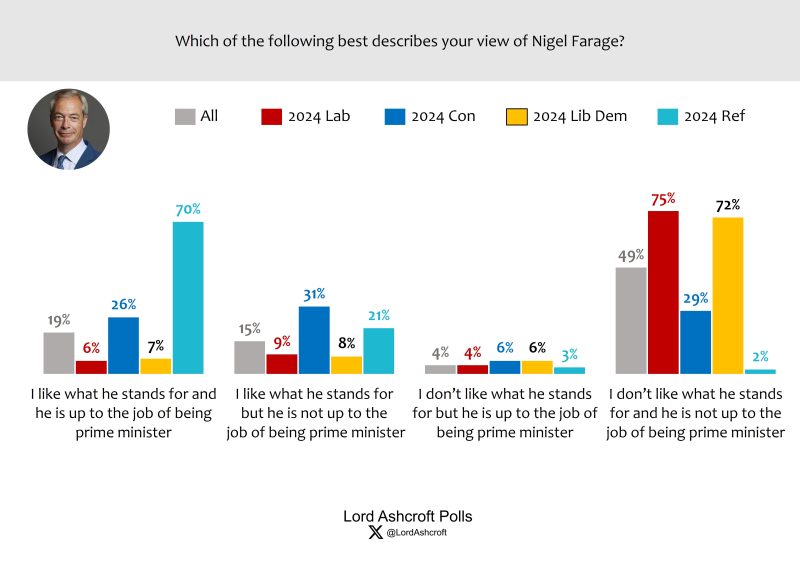

While 34 per cent of voters said they like what Nigel Farage stands for, only 23 per cent said they thought he was up to the job of being prime minister. Of those currently leaning towards voting for Reform UK, just under 1 in 5 (19 per cent) say he is not up to being PM.

While 34 per cent of voters said they like what Nigel Farage stands for, only 23 per cent said they thought he was up to the job of being prime minister. Of those currently leaning towards voting for Reform UK, just under 1 in 5 (19 per cent) say he is not up to being PM.

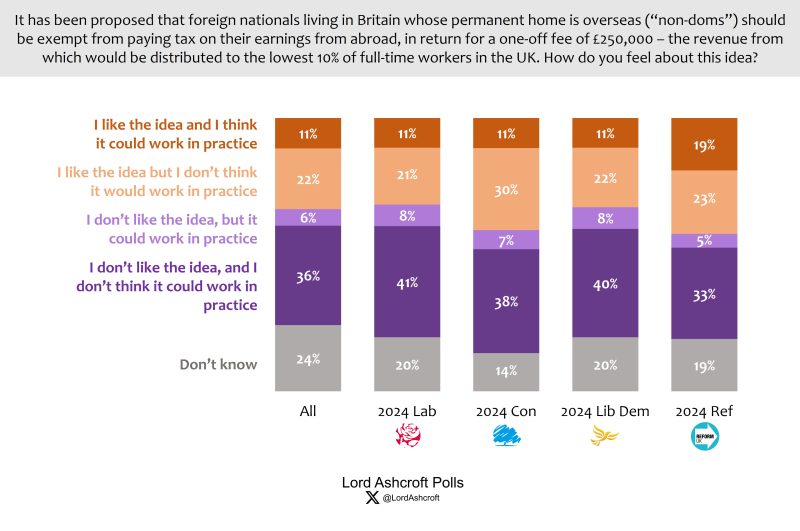

One third of voters said they liked the idea, but most of these said they didn’t think it would work in practice. Reform UK voters were slightly more likely than not to support the idea, but were also more likely than not to think the policy be impractical.

One third of voters said they liked the idea, but most of these said they didn’t think it would work in practice. Reform UK voters were slightly more likely than not to support the idea, but were also more likely than not to think the policy be impractical.

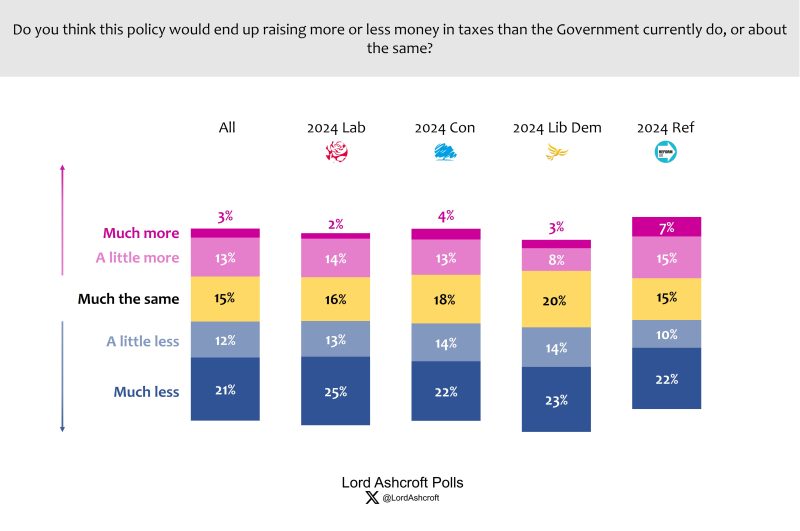

Overall, voters were more than twice as likely to think the £250,000 non-dom fee would end up raising less money than that it would raise more. All voter groups were sceptical, including 2024 Reform UK voters, who thought it would raise less money rather than more money by 32 per cent to 22 per cent.

The political map

As above, our political map shows how different issues, attributes, personalities and opinions interact with one another. Each point shows where we are most likely to find people with that characteristic or opinion; the closer the plot points are to each other the more closely related they are. Here we see that those who are not sure what the government is trying to do appear close to the centre of the map, showing it is a widely held view not confined to any one type of voter. Those who want to raise defence spending to meet the NATO target before 2035 are most likely to be found in the Conservative-leaning top right quadrant of the map – as are those who think the priority in the Middle East is to ensure Iran does not develop nuclear weapons. Those who want to cut defence spending are most likely to appear in the more diverse, less prosperous bottom left – as are those who consider the US strikes on Iran’s nuclear facilities to be completely unjustified. Those who are still giving the government the benefit of the doubt after a year in office are largely confined to the left-hand side of map.

What is driving people?

As in previous surveys, we have asked a series of “mini referendum” questions on issues including immigration, tax and public spending, climate change and economic growth, the parties and leaders, and optimism for Britain. These help us understand more about particular types of voters and what is driving them to support one party or another.

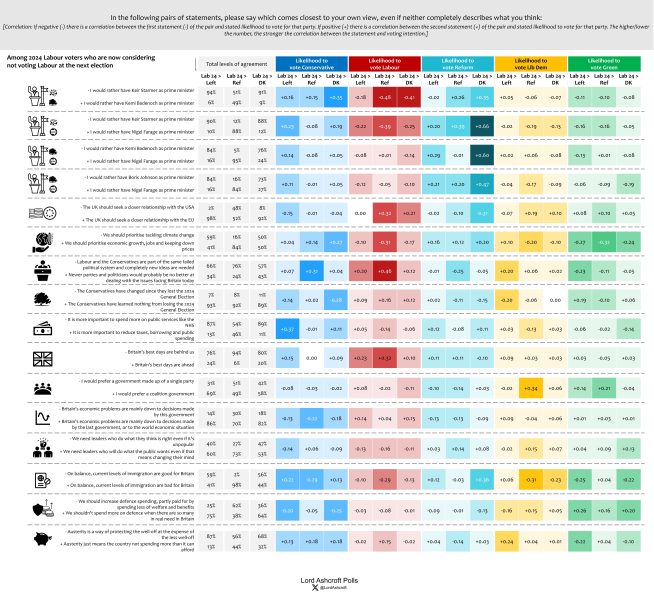

This time we have looked at 2024 Labour voters who are moving away from the party – now saying either that they don’t know what they will do at the next election, that they are most likely to vote for Reform, or that they are more likely to vote for parties of the left (like the Lib Dems, Greens or Nationalists).

Given that all of these voters are disappointed with the Labour government to date and voted to get rid of the Conservatives a year ago, the things these “Labour defectors” have in common are not surprising: they all think the Tories have learned nothing from losing power, they are generally favour of higher public spending rather than tax cuts, they tend to believe that established political parties have failed and they think that Britain’s best days are behind us.

Those who now don’t know what they’ll do at the next election or who favour parties to the left are both pro-immigration, though not overwhelmingly so, whereas those now leaning towards Reform think the current level of immigration is bad for Britain. Labour defectors to “don’t know” and to parties of the left are also overwhelmingly in favour of a closer relationship with the European Union rather than with the US, while defectors to Reform are more evenly divided between the two options.

Defectors to other left-wing parties prioritise climate action over economic growth while defectors to Reform do the opposite, and defectors to “don’t know” are evenly divided between the two. Where defectors to the left and to Reform are currently united is on a preference for coalition over single party government. Defectors to “don’t know” prefer a single party in power and, interestingly are also more likely than other defectors to prefer a leader who does what they think is right rather than one who follows what the public wants.

Full data tables at LordAshcroftPolls.com

![Steak ’n Shake Mocks Cracker Barrel Over Identity-Erasing Rebrand [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Steak-n-Shake-Mocks-Cracker-Barrel-Over-Identity-Erasing-Rebrand-WATCH-350x250.jpg)

![Mount Rushmore Could Get Trump Upgrade Under GOP Push [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Mount-Rushmore-Could-Get-Trump-Upgrade-Under-GOP-Push-WATCH-350x250.jpg)

![Soros Network, Others Behind LA Riots [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Soros-Network-Others-Behind-LA-Riots-WATCH-350x250.jpg)