Editor’s Note: This is the sixth of nine episodes of Scott McKay’s forthcoming novel Blockbusters, offered in serial form as an exclusive to The American Spectator readers in advance of its publication in October. Blockbusters is the third novel in the Mike Holman series; the first two, King of the Jungle and From Hellmarsh With Love, were also serialized at The American Spectator prior to book publication.

Mike Holman, the protagonist in the series, is an independent journalist who’s been called The World’s Greatest Newsman. But in Blockbusters, he’s literally going Hollywood — choosing to head up a campaign chiefly funded by Pierce Polk, Mike’s long-time friend and one of the richest men in the world, to reform and save American and Western culture.

Starting with attempting to fix the film and TV business.

In Episode 5, the effort to revamp American media culture has begun to bear fruit, with a film production company up and rolling with a couple of promising epic projects and the revitalization of an old American classic record label. But the possibilities of a tech-driven cultural renaissance are only beginning to present themself, and Mike and the team are beginning to explore how they can be leveraged to crush the failing status quo in the entertainment industry.

Jupiter, Florida — April 14, 2025

I called Hank back and told him we’d throw some more capital into CASTR like he wanted. But on Morris’ advice, we did it as another convertible debenture rather than a pure equity investment. I had just enough of an understanding of what that was to be dangerous, but I was able to fake it thanks to Morris and Gardocki handling the details.

But then Hank and I got to talking about family, because he mentioned that his dad was broken up over the fact PJ wasn’t answering his calls or messages.

“He wants to talk to her, because Chang Pan-Pacific is having some trouble,” said Hank.

“Are they? I hadn’t heard.”

“Yeah. He’s about to take a massive beating in Australia.”

“Australia? Who cares about Australia?”

Hank laughed, and then he filled me in.

Chang Pan-Pacific was a big player in the import-export and shipping business, and while most of their operations had to do with moving Chinese goods to the west coast of the US and to Mexico, they’d begun moving into the Chinese trade with the Middle East and Africa. And toward that end, The Great Peter Chang — that’s what PJ had taken to calling her dad with a not-small amount of sarcasm, especially after the way he acted since she dumped out of the Secret Service and burned it down after that near-assassination of Donny Trumbull in Indiana last year — had invested a fortune into a port facility in Darwin, on the northwest coast of Australia. It was a way station for goods going back and forth between China and ports along the Indian Ocean, not to mention Europe.

Hank didn’t come out and say it, but he did imply it was also a place where they’d do transshipments — meaning they’d empty the containers from China, relabel everything, reload it and put it on another ship headed for wherever. With Trumbull going in as president and rattling his tariff saber, particularly in China’s direction but also in Vietnam’s because Vietnam is the transshipment destination of choice, it seemed like a smart play to offer up another port where that repackaging could be done.

Knowing very, very little about that business, it sounded like it was a reasonable pivot for The Great Peter Chang to make once all his efforts came to grief to get his old side-piece Pamela Farris elected president after her former boss Joe Deadhorse had that, er, incident at the debate with Trumbull and then made the most dignified exit he could.

Nobody had ever crapped his pants at a televised presidential debate — at least not that we knew of — before Deadhorse did it. And yet, Farris made so many absurd mistakes that they were still debating on cable news whether the Pants Incident, as Scott Jennings was calling it, was even the worst of the disasters the Deadhorse-Farris cabal had blundered into last year.

Chang was one of the biggest backers and bundlers of Farris. PJ had told me why. He’d been banging her off and on since she was a 25-year-old state rep from San Francisco. And we couldn’t prove it, but the suspicion was that Chang was one of the people involved in influencing the Stormer government in the UK to charge me with conspiracy to terrorism for interviewing Robby Thomason last year, which landed me in Belmarsh until Pierce’s guys busted me out.

The Great Peter Chang hadn’t confessed to that. But he had reached out to me once or twice to make peace with me, since I was now his son-in-law and I wasn’t going anywhere. I’d done my best to be gracious; after all, whatever his role in that unpleasantness, he’d failed. It’s not like I’d trust the guy with anything, but you never want to make war with your in-laws.

Besides, Mary, PJ’s mom, was the best. And Hank and I got along really well. I was even friendly with Kevin, PJ’s older brother who was the number two guy at Chang Pan-Pacific.

Anyhow, the port facility in Darwin should have been a good move, and they’d put several billion dollars into fast-tracking it.

But the new Hard-Left parliament in Australia had just passed three new killer taxes — one on unrealized capital gains, another on transshipments and a third on newly-built large-cap infrastructure — and through the vagaries of the brand-new Australian tax laws, these developments threatened to utterly unravel Chang Pan-Pacific.

“He’s absolutely screwed,” said Hank. “I think one of the things he wants to talk to PJ about is he wants to dump a load of cash into her trust fund so that when he gets cleaned out the creditors won’t be able to get at him.”

“Jeez, Hank,” I said. “It’s that bad?”

“Ohhh, yeah,” he said. “He hit me with that, and it didn’t go well because I told him that whatever of his money comes my way I’m putting to work on my own projects. That’s not how he wants it.”

“PJ isn’t going to want to be his straw man, either,” I predicted. “But I’ll tell her to call him back. Or maybe I’ll have Morris do it.”

“That’s perfect,” Hank chuckled. “I hope you do exactly that.”

And after I checked with PJ, that’s precisely what we did.

“Yeah, no thank you,” she said when I told her why her dad kept trying to connect with her. “I’m out. Not involved in his schemes. Happily so.”

And Mary, who was an international trade lawyer, and in fact was Peter’s international trade lawyer, or at least one of them, and who had advised him not to make the investment in Darwin, concurred.

“You don’t want any part of this,” she said when we called her down in Liberty Point.

I asked Mary if she was ever leaving there.

“I kinda like it here,” she said. “And besides, the Guyanese government hired me as a consultant to help rewrite their trade and securities laws to facilitate the Exchange of the Americas, so I’m a little too busy to go back to San Francisco.

“And Peter doesn’t need me anyway. I hear he and Pamela are friendly again.”

“You’ve got to be kidding me,” said PJ.

PJ did not like Pamela Farris. At all. This development was certainly not going to aid in her rapprochement with her father.

The result being that Morris heard Peter out and promptly advised PJ not to get involved in anything her father was proposing, as it was almost definitely illegal both here and in Australia.

The next day, this subject came up when Pierce and I were talking about data centers. Pierce said he had more than enough server space to accommodate the CASTR app, and he asked why weren’t we just buying the damn thing already.

“You realize that with this deal people can download an ebook, then feed it in, cast it and turn it into a movie or a TV series on their own, right?” he said. “You and I have been talking about how the quickest way to reform the culture is to unseat the people who are in charge of it, right?”

“Yeah,” I said. “And what’s the point of a movie studio when any swinging dick with a laptop computer can make movies using AI?”

“If we own the app that allows for this, then we’re the sledgehammer that pulverizes all the gatekeepers,” Pierce was saying, and I could picture him swinging that putter of his around like he always did when he was thinking and talking. “We go and negotiate rights deals with all the actors and the writers, and before you know it you’ll have authors who write novels turning them around into screenplays — or maybe CASTR does that for you when you upload it — and producing them into movies without having to sign their IP over to some studio that’ll make their lead character a Native American non-binary Two-Spirit furry.”

“That’s a lot,” I said.

“Whatever. Go buy that app! If nothing else, Santiago can save a bunch of money in production with the William Eaton movie and this Roman thing.”

“Assuming he can fix Mirabellas’ script,” I said.

“I don’t think it’s that bad. I mean, Act Two is shit, but otherwise? There’s something there.”

Then I told him what Hank had told me. And he started laughing.

“Yeah,” Pierce said. “Chang probably should have bought some better politicians down there. Those are his guys who are flaying him alive. I can’t believe he didn’t get them to carve him out of those insane taxes.”

“I can’t imagine this will last long,” I said. “They’ll repeal it before he’s going to be too badly hurt.”

“Oh, no,” said Pierce. “He gets a torpedo up his butt practically Day One when that goes into effect. He’s got to liquidate half his business or go belly-up and reconstitute as something else, because as I understand it he’s got no wiggle room. We sold all our port facilities in Australia last year when we saw how that election was going. Smartest thing we could have done.”

Another call came in from Bradley Crain, the guy I’d met at LAX who had Redemption Run, that great script about the fake environmentalist pipeline scam.

“I’m emailing you something,” he said.

“OK. The amount of time I’ve got to read things right now is… meager. What is it?”

“It’s the rewrite of Dominus Rex. Chris and I put away almost a case of Shiner last night and finished it.”

“You’re in Corpus Christi?”

“I told you guys to put me on staff at Belmarsh. So Nachman called me and said you guys have office space and a production to work on, and that he wanted to take me up on it. I rounded up my people and hauled ass down here.”

“Your people? You told me you were divorced.”

“Dude, I’ve got 14 people. Writers, actors, production assistants, one’s a key grip. Broke-ass prisoners of the War of the Woke. Chris and Rod said they’d find jobs for us at Belmarsh, so we got a convoy going and made a pilgrimage here. Twenty-five hour drive.”

“Good grief,” I chuckled.

“The whole bunch of us are bedding down in one of the little warehouses,” he said. “It’s like movie camp. Anyway, Chris had made some notes on this Dominus Rex script, and I read through it and came up with my own ideas, and then he and I just pounded down those Shiners and knocked out the masterpiece that’s in your inbox.”

“Excuse me — masterpiece?”

“F**kin’ read it, dude.”

“Wow,” I said. “All right. OK — on your pipeline thing, switching gears. What if we expanded it some and made it a streamer rather than a movie?”

“You want to do it as a series?”

“Ryan Gosling’s people told Rod that’s what they want to do. You know, he’s Canadian. Those people are pretty pissed off about Keystone XL. They like this thing as a long-lasting middle finger in the face of the private jet enviros, and doing it with us is a big power move.”

“Gosling, huh? He’d be the oil company rep? Not bad.”

“This could go very much like Landman if we did it right.”

“Oh, absolutely. Sure. I’ll rewrite it to make it a series. Done.”

I hadn’t even put my phone down and then it rang again. Numakin’s name showed up on the caller ID screen.

“Hey, Bernie,” I said. “What’s shakin’? You see the total carnage over at Castcom?”

The stock had dumped all the way down to $25 after Trumbull’s lawsuit dropped, and though management had done everything they could to deny the Holman Media reports about their Q1 numbers, people weren’t believing them. But for the quiet little buying spree Mainsail was conducting, with help from Pierce’s offshore traders gobbling up Castcom through the exchange in Liberty Point, the stock would be worth a lot less.

“It’s ugly, for sure,” Bernie said, “but I’m calling about something else. Hold on, I’m patching in Stan and Todd, and we’re getting Pierce and the White House.”

“The White House?” I said.

“Yeah. Big things happening.”

A couple of moments later I got to hear those amazing words: “Please hold for the President.”

“Bernie, Mike, Pierce, fellas,” said Trumbull, “I have something I know you’re gonna like and I need you to help me with it. We got Flying Saucer Network and they’re going bust. I want you to buy it.”

Flying Saucer had been around for three decades. It was a satellite TV provider and it was shedding subscribers left and right. I’d forgotten it was still around; what was left of satellite was mostly DirecTV, and even that wasn’t the healthiest company around.

There had been talk, off and on, about a merger between the two.

But something else was going on, and Trumbull was getting around to it.

“It’s a Chinese company. The Zhou Group. They’re big in international trade, shipbuilding, defense contractor for the People’s Liberation Army. And they’ve got a telecom division.”

“Oh, I’m familiar,” said Pierce, in a voice that told you, if you didn’t already know, that the Zhou Group was well-known to him — and not in a good way.

“Well, Zhou has a bid in for Flying Saucer,” Trumbull said. “They want it for $1.5 billion plus assumption of debt, which is $9 billion or so. Deadhorse was gonna let it through, we stopped it when I went in. I’m not selling American birds to the ChiComs, and especially not to the PLA. That’s nuts.”

“But you can’t find a buyer,” said Numakin, “because it’s a dying industry.”

“Mr. President,” said Stan, “we’re putting a lot of money on the line for another move we’re making…”

“Oh, yeah, I know,” said Trumbull. “I heard all about it. Castcom, huh? You’re welcome on that.”

“The lawsuit does not hurt our bid,” said Numakin.

“Anyway, look,” said Trumbull. “You take the debt, throw a billion cash on top, keep it American and I’ll run interference for you.”

“Oh, I dunno,” said Pierce. “Satellites…”

“Hang on,” I said, the hair on the back of my neck standing up. “Bernie, do I remember correctly that Flying Saucer bought Blockbusters Video all those years ago? Do they still have the rights?”

“That’s correct,” said Numakin.

“There’s even still a Blockbusters Video store left,” said Stan. “It’s in some little town in Oregon out in the middle of nowhere.”

“I did a campaign stop at that place last year,” said Trumbull. “Like three days before Terre Haute.”

Terre Haute was where Trumbull got shot, but you know that story.

“We’ll take it,” I said. “Sold.”

“Hey, that’s outstanding,” said Trumbull. “My guy Greg Nessent — you know him, Bernie, he’s got your old job — will get in touch with you. Thanks, fellas.”

And he was gone.

“We want a satellite TV provider?” said Stan. “What’s up with this?”

“I can take the satellites or leave them,” said Pierce. “I imagine we can integrate them with Skynet, but…”

Skynet was the brand name Pierce was giving to his satellite network. I was pretty sure we were going to have to convince him to go a different direction, but that was for another day.

“Look, Pierce” I said, “you were about to spill the beans to Trumbull that you were going to make that network go commercial. If you’d told him that and then we went forward with buying Flying Saucer, I can’t tell you how bad the politics would look for him.”

“Ahhh,” said Pierce.

“Yes,” said Numakin. “Good thinking.”

“Yeah, but why say yes and not no?” said Stan. “Flying Saucer is a dog with fleas.”

“Blockbusters,” I said, “is the name of our streaming platform we’re going to build. And now we’ll own the rights to it. As well as the undying loyalty of the Trumbull administration for giving them a win here, which is something we’re going to want at some point.”

“Oh, hell yes,” said Gardocki.

“Dude, you’re getting the hang of this,” Pierce laughed.

Jupiter, Florida — April 27, 2025

As you might imagine, given all the things we’d put in motion, there were lots of developments which came in pretty quick succession.

The best of them, and this was the highlight of my whole life to that point, was the onset of PJ’s rather intense campaign of projectile vomiting.

OK, let me rephrase that so I don’t come off like a psychopath. The projectile vomiting turned out to be morning sickness, and we realized that on the third day of it when she came home from Walgreen’s with a pregnancy test and it dropped positive.

So now we knew that Robby The Furry, Biting, Peeing Terrorist wouldn’t be the only sub-adult at Chez Holman. PJ was so thrilled, she even took a congratulatory call from Peter.

And he didn’t bring up the idea of using her as a straw man to hide his assets from whatever creditors he was presumably going to try to fleece.

I was happier about the pregnancy than PJ was, but not for any serious reason. Stan had turned us on to this little winery in the Sonoma Valley that made an incredible cabernet, and literally the night before PJ’s first over-eventful morning the case of it we’d ordered came in. We drank the first bottle that night.

She just thought she was hung over. She was a little less convinced of that when she still felt sick on the second day, after having no booze. Then on the third puketastic day, she found out she was pregnant, and shortly after that, it hit her that she’d be out of the wine-tasting game for the rest of the year.

“This is so unfair,” she said. “You’re gonna drink all of that amazing wine, aren’t you?”

“I’ll do you a favor,” I said. “I’ll drink it quickly.”

Strangely, that didn’t go over as well as I expected. But we did agree that I’d save her at least one bottle for after the bun came out of her oven.

And then I humored her, because she insisted we spend that day, which was a Saturday, turning the third bedroom into a nursery. For almost every second of my life prior to that moment I would have regarded shopping for baby furniture as utter and complete torture, but I’ve got to say that it wasn’t that bad.

Other than the colossal fight over what color to paint the walls. PJ said they needed to be blue, because obviously our first kid would be a boy.

“How on earth would you know that?” I asked.

“Because I just do,” she said. “Are you really going to doubt me about that? I always know these things.”

She wasn’t, strictly speaking, wrong in that regard.

I managed to win something of a compromise, in that we picked out a shade of blue and one of pink. And then I won a massive victory, in that I was able to stall the painting of the walls until we knew what sex that kid would be.

And I was for damned sure going to hire somebody to paint the walls of that nursery.

Besides, I assembled that crib, that Swedish torture device PJ insisted on, with no help, I’ll have you know. I’d say I was a good eight months early in putting it together, and I wasn’t really persuaded by PJ’s argument that it was best to get everything done and that would help to get both of us excited about the pregnancy, but again — it was fine.

The pregnancy discovery was the top highlight, but that week saw others.

For example, we went ahead and bought CASTR. I’d say we got it amazingly cheap. Of course, stroking a check for $25 million to buy anything is an act which by definition feels like the antithesis of cheap.

But as Gardocki reminded me, and so did Hank, this was a multi-billion dollar idea. And the 35 percent rev-share that Hank, Vinesh Patel, Billy Slaton, Sri Balakrishnan, and Aidan Gromsky split up was where the real money was going to be made.

Plus we put them to work right away, because part of the deal was they’d build out a CGI farm for Belmarsh Entertainment. We’d get first crack at making the AI movies the app was built for making, and then roll it out to the consumer market later.

And before we bought CASTR, we asked them for a demonstration of the 2.0 version, which was the one in which you could make a movie or TV show from a screenplay you loaded in.

That’s when Derrick Washington, who was one of Bradley Crain’s pals who made the trek from L.A. to Corpus Christi, asked if he could guinea-pig that 2.0 version for a script he’d written. We had a huge debate over which one we’d go with, because there was a lot of sentiment in favor of running Crain’s revised script for Dominus Rex. That thing was unanimously regarded in our building in Corpus Christi as a film classic in the making — Gladiator meets The Godfather meets Passion of the Christ, was what Nachman said after he read the new draft of the screenplay.

But we ultimately went with Derrick’s project, just because it fit the AI model a little better.

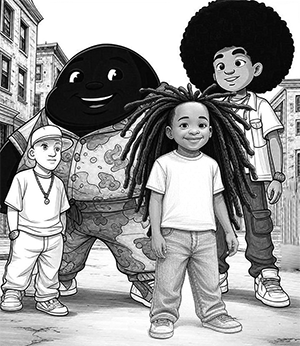

It was an animated kids’ TV series; a takeoff on the old Bill Cosby Fat Albert cartoons that he called The Hoodrats. These were hilarious caricatures of the kinds of kids you get in the ghetto — one was a giant, Kool-Aid man-looking jet-black kid who didn’t say much but was always doing crazy stuff, another one was a Puerto Rican mixed-race kid with a massive afro, then there was the Vanilla Ice/Eminem white kid from an atrocious background but who never would give up on life, and the fourth kid was the Jamaican immigrant with the accent and the nonstop get-rich-quick schemes.

Everything about the show was politically incorrect as hell. But not in a way that was really offensive, if that makes sense. The characters were all lovable as can be, just like the Fat Albert characters were. In other words, they were intentionally, overtly stereotypical — and you were supposed to love them anyway, which you couldn’t help but do.

And he had like three seasons’ worth of episodes scripted out. They were funny to read. But when Derrick insisted we let him read the first two episodes dramatically to us, he had a whole warehouse full of people, plus the bunch of us who were Zooming in from PGFI’s offices, utterly in stitches.

I’m a child of the 1980s. As I noted, funny to me is Animal House, Porky’s, Caddyshack, Blazing Saddles. Gross-out humor bores me, and so does Seth Rogen stuff.

Derrick’s series was my speed. And Stan, who’s about my age, agreed.

But what really impressed me was that Melissa was literally crying, she was laughing so hard. So were the CASTR guys.

The episodes we read had lots of the crappy stuff which goes on in the ghetto — this show was set in South Philly, where Derrick was from — but the message of all of them was wholesome almost to the point of hokey. They were deeply Christian but in a really artful way, like Derrick never wrote scripture into the screenplays but yet the philosophy and moral lessons were obvious the minute you saw them play out. It was all golden-rule, do your best, delayed gratification, respect your elders. The Hoodrats were zany, hard-bitten and streetwise, but they were good kids.

Gardocki, who’s in his mid 30s, said it was a damned tragedy he never had a TV show like that to watch when he was a kid.

And Stan and I were looking at each other thinking this was a billion-dollar piece of IP if it was a dime.

“Boss, you gotta let me put this in the app,” said Derrick. “If these dudes ain’t bullshittin’ you, it’s gonna be the bomb.”

“Absolutely,” I said, after agonizing over it a little. And I could hear Nachman agreeing. So I told Hank and Vinesh we were going to use the first episode of The Hoodrats as a pilot for the CASTR app.

They were really, really excited to do it.

It took about 20 hours for the app to generate the first hour-long episode after Derrick finished storyboarding it — he had already done a lot of that using Photoshop and Stable Diffusion to generate still images for the scenes as he was pitching the scripts in Hollywood (and getting nowhere because they said his concept was outdated).

But the product that came out was utterly revolutionary.

These were caricaturish comic-book characters. Derrick had drawn the show to look like the old Fat Albert cartoons. But when the app animated them, they moved like live-action figures — Vinesh and his guys had calibrated the AI to process everything along the lines of the films they’d loaded in, which were of a wide range of film eras and film tech, but everything they’d used was live action, and because of that it presented cartoons as real life photography.

It was striking. Almost creepy, but more than that it was impressive.

Derrick was a really good voice guy who had a great deal of acting talent, so he didn’t have to do a ton with the voices to get them to sound like completely different characters. But when he was finished, the voiceovers, all of which were AI derivatives of Derrick’s voice, sounded 100 percent distinct. The Jamaican kid, whose name was Desmond, reminded me of a younger version of Denzel’s character in The Mighty Quinn. And Luis, the Puerto Rican kid, came off a little like Leguizamo. The Vanilla Ice kid, Jordan, was sort of Seth Green. And the fat black kid, whose name was Latrell, sounded like Charles Barkley as a kid.

It was the most entertaining thing I’d seen in decades.

And when PJ and I watched it at the house, she was absolutely blown away.

“This is real, right?” she said. “You’re buying this? They didn’t spend months and millions of dollars doing animation to make it?”

“It didn’t exist a day ago,” I said. “It was a script, Derrick’s voice and a bunch of still images he’d made on his computer. The app turned it into a TV show in 20 hours.”

“Oh my God.”

“I’d say we have a winner,” I said.

“The show, or the app?”

“Yes.”

“I agree.”

We also bought Flying Saucer, or at least we went to their management team and nailed down a deal. Things turned out to be a little complicated, at least beyond the sale. While what I wanted was the Blockbusters name and I didn’t care all that much about everything else that was in their package, and most notably Jump Mobile and Fling TV, others in our group were a lot like kids on Christmas morning.

For example, Mark Green was already an utter geek about satellites, which was probably a qualification as the CEO of Sentinel Telecommunications, but when we bought this thing and essentially dumped it in his lap his first reaction was to spout an absolutely unintelligible monologue about how the multi-layer integration of Flying Saucer’s satellite and 5G cell-tower network with Skynet would boost durability and enable content caching and…

Mark went on and said all kinds of things which I could tell were very exciting somehow. What I took from it was that the merged system would be carrying a gargantuan bandwidth and that it would solve one of the vulnerabilities of Skynet — sluggish internet when it was cloudy or if you were in a city with lots of tall buildings or somewhere there was a lot of tree cover. Jump Mobile’s cell towers covered something like 80 percent of the country with 5G, and they were a backup for the satellite network to insure customers would get pretty close to 300 Mbps download speeds anywhere, in any kind of weather.

It sounded like this was a nice win. Pierce was saying that for a billion up front and nine billion in debt assumption it was a bargain.

“Yeah, but you’ve got to get this thing to spit out some revenue soon, right?” I said.

“We have seven million cell phone customers paying every month now,” he said. “Plus another eight million between Fling TV and Flying Saucer’s satellite TV service. Put that together with Skynet and now you’ve got bundled connectivity on all of your devices.”

“And we’ll rebrand Jump Mobile,” said Stan. “Something patriotic. After all, we bought this thing to keep it away from China, right?”

“Like Mobile 1776,” said Gardocki. “Or Yankee Mobile.”

“They’ll hate that in the South,” said Pierce.

“Guys,” I said. “What are you doing? We’ve already got the name.”

“Oh, right!” said Green. “You mean Blockbusters.”

“Exactly,” I said. “We leverage this thing across the board. Your cell service, your wifi, your streaming TV. And it’s all a blockbuster; that’s the point.”

“So Fling TV is Blockbusters TV, and Jump Mobile is Blockbusters Mobile,” said Stan, “and Skynet and Flying Saucer is Blockbusters Internet.”

“One big brand,” I said, “and it works for three reasons. First, it’s so awesome it’s a blockbuster. Second, because what we’re going to build is going to be basically an aggregator of an entire ecosystem of cultural and technological content…”

“You mean we’ll end up as a common carrier,” said Pierce.

“I haven’t gotten that far,” I said, “but yeah. Maybe. If we end up as something like a utility company for connectivity, and what comes from that is we open the skies to a panoply of content of every kind.”

“He said panoply,” said Stan.

“He always was a wordsmith,” said Pierce.

“Oh, shut up,” I said, as the rest of these clowns snickered over the Zoom. “The point is that the Big Five oligopoly that the media sector is right now would get blasted to pieces, and that’s a literal blockbuster.”

“Oligopoly,” said Pierce, his voice dripping with insincere admiration.

“The third reason,” I said, ignoring him, “is that we are going to produce so much blockbuster content that it’ll kick off a cultural renaissance that revives not just America but the West.”

“It’s awesome. I’m on board,” said Stan.

I let them kick around my ideas, and a few days later Gardocki put together a memo which outlined how we’d put all of this stuff together, and it was really, really good work. So much so that Pierce called it the Bible. It was a plan whereby we’d all but eliminate the barriers between your phone, your tablet computer, your laptop or desktop and your TV — they’d simply be devices from which you’d connect.

The next generation of smart TVs would allow you to make video calls, for example. You could do Zoom calls through them, and their remotes would have full keyboard interfaces. I sunk my teeth into that, because the thing I was concerned about was that this technology would have the effect of further isolating people rather than connecting them, and so some of the ideas we came up with were things like video fan discussion groups that you could join after you’d watched a given show right there on the same app where you’d watched it, and apply that concept to sports, or music, or church.

And we brought Harnett in on that discussion and he said he’d incorporate that in the Movie King redesigns. There was literally no end to what he could do with that, he said; hosting discussion groups after shows was literally the best market research anybody could get and people would have fun participating in it.

The second draft of the Bible incorporated a bunch of Pierce’s ideas for the CASTR app which would allow the consumer to program their own custom movies and TV shows from drop-down menus that would be built off Fling TV’s interface — which was going to get a major facelift in its own right. And Harnett threw in an idea there, which was that you could be a film student or a content creator or anybody with enough time or energy to get into that app and make something, and you could set up your own premiere at the local Movie King of the film you made.

Or, Gardocki noted, you could enter your CASTR-created AI film in a contest, with a movie deal as the prize. And your friends would show up to support you and vote it up, all the while having dinner, drinks, and whatever else at the Movie King.

It was like an American Idol for content creators. You didn’t have to look like Beyonce or sing like Jennifer Hudson, and the public could still enjoy judging your creations. Harnett did a little focus-grouping at the Movie Kings that he had open and the scores that idea was generating were exceedingly high.

There was a whole lot more. Pierce suggested we bring in some consultants to help us brainstorm, and Gardocki said he’d spearhead that.

This part was the most fun I had with the whole PGFI effort. We were, in a not insignificant way, redesigning American life. And what we were doing needed to be done, because it struck us that we’d been deluged with all this technology that had made massive changes to our lives and lifestyles in ways that were certainly positive in theory — but in practice they were making us more anonymous, more disconnected, and more alone.

This project, which had started as an effort to find the next Chuck Norris and then a crusade to break up the media cartels, was quickly becoming a real stab at the heart of our cultural malaise. Reconnecting people through a revitalized, tech-aided artistic and social flowering that somebody was thinking through and designing in a way that added to our humanity rather than detracted from it? The attempt to do that was like a jolt of energy.

And PJ, who had been impressed with the scale of the project initially as a theoretical thing and then not very impressed at all when she thought this was just me playing Mr. Hollywood, was beginning to see it for what it was becoming.

She was glowing, and not just because she was with child.

“I literally don’t think I could be any prouder of you,” she said.

“Really?”

“Really. This is absolutely amazing. You might end up being for this generation what Steve Jobs was for the one before.”

“Damn!” I said.

“I’m not kidding.”

And then she said something I’ll never forget.

“And I think you might end up being more consequential than Pierce.”

That one stunned me. I never, ever thought I’d hear anybody say anything like it. And I just looked at her, dumbfounded, until she smiled at me and put her hand on my cheek.

“You ready to take the pregnant girl to bed?” she said.

“Uh huh,” I said, after a gulp.

Harnett’s Movie Kings were beginning to come online. The one in Fort Lauderdale, which had a capacity of 2,100 people between its seven units, was already booked with a five-week waiting list, and they’d set up a standby lounge in the parking lot with food trucks and portable big screen TVs showing Marlins games and something Harnett and Frank Taylor had come up with — namely, a bunch of remastered video of Sunshine Records’ greatest hits.

Using the CASTR app, naturally.

It turned out that Billy Slaton, who was from some dinky little town in southeastern Ohio, was a massive fan of old, OLD country music, the stuff Sunshine was born on. And when he found out we now had the rights to all of Sunshine’s stuff, he started cranking out music videos from those great old songs using the AI.

They were terrific. Santiago, who was one of the best music video directors out there, said he’d been wasting his time doing it the old-fashioned way.

“But you shouldn’t do any of this where the artist is still around,” he said. “It’s a question of ethics.”

“Agreed,” I said. “I think this is a way to resurrect classic American music and make it relevant again, like classical music has been resurrected again and again.”

“My rule for the life of the deal we’ve done with Belmarsh,” he said, “and you know this, obviously, but for the purpose of this conversation I’m gonna restate it, is that I’m always going to use human actors in my cast. For everything the camera focuses on, including extras. Beyond that I’ll employ AI. And that includes off-camera stuff that I can do with AI.”

“I think that’s a good rule,” I said.

“I did an interview with Variety the other day and they asked me about that, because I guess the word is out that I’m revamping production with Desert Odyssey. I’m using probably a third of the crew a regular production of this size would use because we’re going to do so much AI post-photography. What I said was that because we’re going to streamline so much of this and get by with so few moving parts, we’ll be able to finish a project in a third the time with less than half the budget.”

“It’s amazing what you’re doing with that film,” I said.

Santiago had started with principal photography of Desert Odyssey on a deserted beach on North Padre Island and in a desolate plot of land on the King Ranch where they’d let him bring in Sentinel Construction to slap up a 3D-printed Arab fortress. What was crazy, though, was that he’d bring in a dozen still photographers to shoot the scene from all the angles that would conceivably appear in the final product, and then he’d shoot it with the movie cameras. But what he wouldn’t do was to go through take after take to try to make it perfect.

“We don’t have to do that anymore,” he said.

Instead, and he showed me his new version of dailies, he’d shoot maybe two or three takes of a scene that would essentially be intentionally different versions of it. And once he had them on film, along with the still shots, some from the same angles and some from different ones, the whole thing was getting fed into the CASTR app and he would be adjusting everything from there.

So, for example, Parker Stone — who from the raw film I’d seen was pretty good in the lead role — was being digitally enhanced into a perfect William Eaton.

Santiago reiterated, forcefully, that he wasn’t doing anything that couldn’t be done with old-fashioned movie direction and enough time and repetition. It’s not like he was making Parker different. It was Parker. He wasn’t applying filters or any of that.

But he was enhancing facial expressions. Changing voice inflections subtly. Making minor adjustments to hand gestures.

The point being Santiago could get exactly what he wanted digitally in a few seconds or minutes that he might have to take an hour to shoot a half-dozen takes, with direction in between, the old-fashioned way. And he argued that because he was still using actors and cameras, what he was doing was very much still within the confines of ethics.

Interestingly, the public reaction to that piece in Variety was fairly positive. Within the industry it was histrionic.

Mark Ruffalo called me a “f**king vulgarian.” Jimmy Kimmel gave a monologue on his show saying we were a bunch of “troglodytes.” Bette Midler went on X and posted a long diatribe saying that we had killed her beloved show business.

I’m not even going to waste your time with the stuff George Takei and Rob Reiner said about Santiago and me.

What they didn’t bother to understand was the flip side of how Santiago was using the CASTR app.

Namely, he would use its AI to pre-generate what he wanted from Stone and the other actors on the set. So it wasn’t just Santiago telling them what he wanted; he was showing them as though they were looking in a mirror. And what he found was that when he did that, and they knew exactly what they were supposed to imitate, the delta between the raw film and what he wanted shrunk very noticeably.

So it was also a training aid for acting and direction.

Chris was able to turn some of the scenes over to Mary McLaughlin, who was the assistant director on the picture, without hitting a seam, because he’d agreed to take on Dominus Rex as a producer/director and he was splitting his time with the two.

These were two epic projects and he was now going to work on them simultaneously, at least to an extent. I was adamant that it was a bad idea.

Nachman talked me down. He said it would be fine. And the more I saw of what Chris was doing, the more I backed off.

I didn’t know anything about how an AI-enhanced principal photography process worked, though obviously I was learning. But Nachman, in town for some meetings with Stan, Gardocki and me at PGFI’s offices in Jupiter, told us Santiago was getting eight weeks’ worth of principal photography done in less than 20 days because of his process.

“This is how it’s going to be done going forward,” he said. “You couldn’t do this before the current tech he’s using. But it’s a revolution.”

“The question is how many people it’ll turn off,” Stan worried.

“Nobody,” he said. “Why would it turn them off? We’ve been using CGI since the 1980’s. What we’re using it for now is to replace a lot of the old grunt work of making a movie.”

“I’m on board,” Stan said. “I’m just nervous that the old-school crowd will use the narrative that all of this is fake filmmaking and people will believe it.”

“So what’s the argument?”

“Well, I know they’ll say your cast and crew will get short-changed and not make as much money,” said Trent.

“But we’ll be making multiple times more IP,” Nachman said. “What do you care if you work six months on six projects instead of one?”

“Well, that’s the sea change,” I said. “and if we establish that, then we’ve won.”

Nachman just smiled.

“Time, fellas. Time is very much on our side.”

“I believe it,” Gardocki said. “It’s why we’re here.”

Something else happened that third week of April. Namely that Shri Bundarahman got the axe at Summit after their first-quarter earnings report came out. They were badly in the hole, and Bundarahman came under a huge firestorm because he’d replaced the entire accounting department at Summit with H-1B visa guys from India. He said it was a cost-cutting measure, which obviously it was, but it was also a goodwill-cutting measure that Summit really couldn’t afford after the dumb statements he’d already made. And then a video surfaced of a speech Bundarahman had given when he’d addressed a group of students at Cambridge back in 2010, and it was the last straw.

He’d said that the West was going to have to reconcile with the fact that its time was over, and so were the philosophies which underlay its politics and economics. He launched into a discussion of how this was obviously true on the streets of Great Britain, but that in American media culture, which he’d just been hired to join as a VP of corporate communications at Stine-Warmer at the time, it was unquestionably also true.

The internet rose up and ate him after that video leaked, and Bundarahman hit the eject button.

We brought that up in our Zoom call that afternoon, with the question on the table whether we should make another takeover bid on Summit.

Stan suggested we hold off and see if the stock would drop under $10.

“I’m guessing it will,” he said, “and with the work we’ve already done we’re really just buying production and IP archives at this point. That says ‘discount’ to me.”

Nobody argued with him, mostly because we still had the Castcom bid on the table.

But then Numakin piped up because he had another call from Trumbull.

“He wants us to buy Surge Vision,” he said.

“What’s that?” I asked him. “It sounds sort of familiar.”

Surge Vision was one of the mini-major film studios. Perhaps “mini-mini-major” would be the best way to describe it. Surge was making a lot of low-budget streaming shows that would get on the lesser streaming platforms, and a smattering of straight-to-streaming B movies. None of it was pulling a lot of revenue.

Trumbull wanted us to buy it because Surge Vision was another target of the Zhou Group.

“China already has one movie studio in the U.S.,” Numakin was saying, meaning Legendary Pictures. “He thinks that if they get two of them, together with some of their ownership interests in the Big Five, this starts to look like a cultural takeover.”

I knew nothing about these guys. But Gardocki said he’d do some research and get back to us.

That was April 20. On April 21, Castcom’s Q1 report was due out. The stock opened at $23.25, and the report was every bit as terrible as Harrison said it would be.

But that didn’t crash Castcom’s shares. They went up.

Gardocki told me this was a very bad sign. And all through the morning Castcom was rallying, inexplicably.

Stan knew why.

“That stock is in play,” he said, “and the word is Fleet is going after it.”

The Fleet Fund was a big institutional capital outfit run by a guy named, I kid you not, Don O’Henley. They’d suffered a lot of bad press in recent years for embracing all the DEI stuff and helping to pioneer that ESG investing crap. O’Henley was a big proponent of it, and he’d fly his Gulfstream to all the climate conferences to give speeches about how Wall Street was going to save the planet by making the oil companies capture carbon dioxide and pipe it into the ground.

O’Henley had been the best man at Alberto Goroz’ wedding to Uma Ramadan, the infamous Democrat staffer who’d been implicated in a number of Omobba’s scandals. Goroz, the son of Serge Goroz, the big currency speculator and leftist moneybagger, had been very quiet in the aftermath of the release of that tape from the hookers-and-blow party Fisher Deadhorse had thrown, the one in which it came out that they were pressuring the Stormer government to keep me in jail through the election last year. Everybody expected Goroz was going to get charged with something; that hadn’t happened yet.

And I wasn’t making a big deal about it. Yet.

Anyway, the word was out on Castcom, the stock was skyrocketing and by the market’s close Fleet had gained control. O’Henley called a press conference to celebrate, and of course Alberto was there.

They’d tendered the stock at $34, which was utterly insane. Under no circumstances was Castcom, with its dreadful earnings report and shrinking audience, worth anything close to such a price. And O’Henley was warbling about some sort of gold mine Castcom offered in the way of carbon credits in the EU through its innovative use of fiber optic cables.

None of us had the first clue what the hell he was talking about.

Stan and Pierce weren’t upset at all. Pierce was actually texting me laugh emojis while that press conference was on. I guess I wasn’t too angry, either, or maybe I was used to the disappointment of trying to buy one of the Big Five only to fail.

But this time, we agreed that we’d go public on the subject rather than to clam up.

So I started saying yes to interviews. And for the next two days I gleefully shat all over not just Castcom, and not just the Big Five, but the entire outdated, underperforming model of major media in this country.

“As we’ve embarked on this quest to reform our culture,” I said when CNBC interviewed me, “what I’ve noticed more and more is this system of gatekeepers and channels can’t really survive a lot of scrutiny. So we’re really in the acquisition game more because we want to get our hands on the great intellectual property archives these companies hold, that frankly not many of them are great stewards of. We don’t care how many cable channels we control. We’re not sure cable channels will survive the next decade anyway.”

That generated a lot of buzz. Most of it was negative.

And somebody from one of the papers — I can’t remember if it was the Post or the Times — asked Trumbull about it. He gave a really interesting answer.

“Nobody should be trashing Mike Holman,” he said. “Holman is an American hero. Got that? An American hero. And he and his group have had a lot of success. Those Movie Kings? They’ve never seen anything like it, the do-overs they’re doing. And Mike went and saved our beautiful satellites, because if it wasn’t for Mike, and also for me, frankly, those satellites would have gone to Chy-na.”

It was in the middle of that frenzy in the days after the Castcom fiasco when the phone rang at PGFI and a guy by the name of Grant Paxton called, and that was a whole lot more interesting than any of the Castcom stuff ever was.

![ICE Arrests Illegal Alien Influencer During Her Livestream in Los Angeles: ‘You Bet We Did’ [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/ICE-Arrests-Illegal-Alien-Influencer-During-Her-Livestream-in-Los-350x250.jpg)

![Gavin Newsom Threatens to 'Punch These Sons of B*thces in the Mouth' [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Gavin-Newsom-Threatens-to-Punch-These-Sons-of-Bthces-in-350x250.jpg)