Adrian Lee is a solicitor-advocate in London, specialising in criminal defence, and was twice a Conservative parliamentary candidate.

As the year 2025 has progressed, there has been increased focus upon issues relating to immigration and what used to be known as race relations. Whether it is the small boats crisis, grooming gangs in northern England, asylum-seekers living in market town hotels, Nigel Farage’s relentless campaigning, fears of overseas sexual predators or the wave British flags festooning suburban lampposts. It is no wonder that immigration has become one of the public’s main issues of concern.

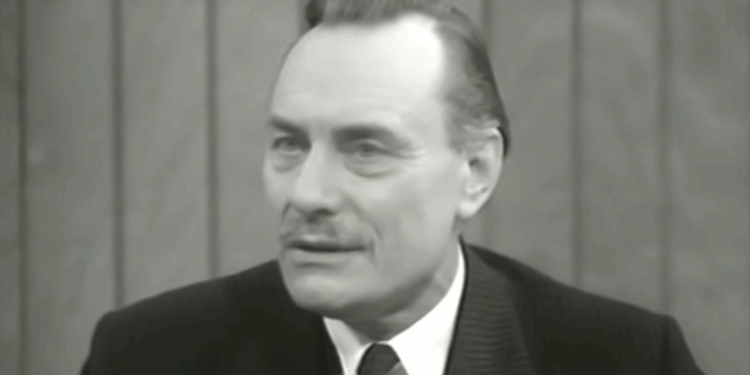

Perhaps inevitably, there has been an increased interest in Enoch Powell. Douglas Murray recently wrote in The Spectator about the accuracy and impact of Powell’s prophetic “Rivers of Blood” speech, delivered to a weekend meeting of the Birmingham Conservative Political Centre (C.P.C.) at the Midland Hotel on Saturday 20th April 1968.

Similarly, Dominic Sandbrook and Tom Holland devoted an episode of their history podcast, The Rest is History, to the life and legacy of Enoch Powell. However, it should be recognised more widely that there was far more to Powell than just his views on immigration. Most Conservatives acknowledge him as one of the founding fathers of British monetarism, but few realise that his second radical, and at the time equally controversial, speech of 1968 concerned the burden of taxation, another issue that is likely to grow in significance in times ahead.

Conservative Party Conferences of the 1960s bore little resemblance to those of today. For a start, they were held mid-week at the seaside, usually rotating between Blackpool and Brighton. The conference was organised by the National Union of Conservative and Unionist Associations, and, as such, was the voluntary party’s conference, although members of the parliamentary party were encouraged to attend. The Party Leader only appeared on the last day to address members. This emphasised that he was essentially a guest at the member’s event. Finally, in an age before the invention of think tanks, the conference fringe was virtually non-existent.

In 1968, the conference was staged in Blackpool but following the Birmingham speech earlier that year and his dismissal from Ted Heath’s Shadow Cabinet, there were few opportunities for Powell to make a speech during conference week. So, Powell accepted an invitation to address an evening function on the 11th of October, over thirty-nine miles to the north of Blackpool, in Morecambe.

Few today would make a speech so far away. What journalist in his right mind would venture so far from the conference to hear the speech of a political exile. Powell, however, was unique and transfixed Fleet Street’s imagination. Each speech comprised an element of his message to the country and radically departed from the Butskellite post-war consensus. Those who attended that evening were not disappointed.

Powell opened by stating:

“The trouble with this nation is that we have been brainwashed for years into believing that ‘it can’t be done’. Britain has become the ‘Mr. Can’t’ of the modern world. There are too many who are glad to sit around, like Job’s comforters, explaining why no great change is possible and that therefore she had better like it or lump it.”

He then addressed the nationalised industries, which at that time “…put nearly £1 billion a year on to the borrowing requirement of the Exchequer and lost another £180 million a year on top of that.” Powell said that whilst many were frustrated by the inefficiencies and cost of the public sector, majority opinion would not entertain the notion of “…calling in private enterprise and the capital market to do the job”. He continued:

“The same applies to taxation. We have got into a frame of mind in which we are resigned to carrying approximately the same load of taxation until Kingdom Come, and think ourselves mightily lucky if it gets no heavier.”

Powell then turned to the economics of Harold Macmillan’s government, from which he had resigned in January 1958 as Financial Secretary to the Treasury, along with the Chancellor, Peter Thorneycroft, and Nigel Birch, Economic Secretary to the Treasury, in protest at the Government increasing public expenditure. This will have a ring of familiarity to modern readers and remind us of the fact that when Sunak’s government fell in July 2024, taxation was at its highest level since Clement Attlee’s time.

“Why only yesterday the Conservative Party conference chose to debate not reduction of taxation – oh dear, no; nothing so wild and irresponsible as that – but taking a bit of taxation off some people and putting it on other people. Mind, you can hardly blame the public if they regard the tax burden as a whole as being something no more to be altered than the English weather or the other dispensations of Providence. After all, during the thirteen years of Conservative administration, they watched the proportion of public expenditure to national income move downwards until 1958 and then move back up again till it was at the same level when Labour came back in 1964 as when Labour went out in 1951.”

Powell then revealed to his audience that he intended to prove that both income tax and surtax could be halved by a Conservative government. He did not think that all the measures could be achieved in one budget but could happen over the course of a Parliamentary term. Powell did not underestimate the scale of the task:

“All government expenditure is popular with somebody, and large government expenditure is popular with large numbers of people. There will be few items in my package which will not make somebody wince. Please remember all the time that the choice is yours; but if you are going to get big results, you must take big decisions. Painless it cannot be, nor can it be done in a hole or a corner without anybody noticing.”

He then detailed his proposals. All industrial investment grants would be abolished, saving £360 million, as would assistance to development areas, saving £250 million. Wilsonian quangos, such as the Industrial Re-organisation Corporation, the Prices and Incomes Board, the Shipping Industry Board and the “Neddies” would be scrapped, saving £54 million.

Next to go would be the Land Commission and Labour’s beloved Ministry of Technology, which had failed to generate the “white heat” that Wilson promised. This would save £20 million.

Agricultural expenditure would be reformed, in line with current Heathite policy, accruing £250 million in savings. Overseas aid would be abolished, producing £200 million. Housing subsidies would be gradually phased out and housing provision returned to the private sector.

The list was long and detailed, and the savings were precisely calculated. There was no relying on the generalised “cutting government waste argument”, that is frequently trotted out by politicians to this day.

Powell then turned to the nationalised industries. Government subsidies currently included £170 million for transport, £800 million for power generation, £100 million for steel production, and £49 million for British Airways. Enoch Powell proposed, for the first time in the public expenditure debate, that the old commercial companies previously nationalised by Labour now be privatised. Only coal mines and railways “just for the moment” would remain in the public sector.

As the speech drew to its close, Powell condemned the practice of the times “…to manufacture the extra money, thus sending prices up and pushing the pound further down.” He favoured strict monetary control, paving the way for monetarism eleven years later. The Morecambe budget speech concluded thus:

“By all means, if you prefer it, go staggering along with your present growing load of taxation, with your present diminishing voice in the disposal of the national income which you create. The process slowed down a little at first when the Conservatives were in, and it has speeded up again since the Socialists came in: but the caravan still moves unmistakenly onward and upward. If that is your pleasure and your decision, by all means go along with it. But let it never be said that you took no decision at all because you thought that there was none to take. Only that it was impossible which you have not the will to do.”

The speech, whilst attracting great media coverage, was widely condemned. However, along with an earlier Powell proposal of council house sales, the Morecambe speech laid the foundations for the Thatcherism of the 1980s.

![Keith Ellison Caught Promising to Fight State Agencies for Somali Fraudsters [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Keith-Ellison-Caught-Promising-to-Fight-State-Agencies-for-Somali-350x250.jpg)