Alexander Bowen is a trainee economist based in Belgium, specialising in public policy assessment, and a policy fellow at a British think tank.

“Boris well he’s the life and soul of the party, but he’s not the man you want driving you home at the end of the evening”

It was, if you can remember 2016 still, the stand out line from June 9th’s Brexit debate. A, by that point expected, blue-on-blue attack in the form of a semi-questionable drink driving reference, made surprising only by the fact that said zinger was delivered by Amber Rudd who was shall we say perhaps not known for her vast charisma.

Sandwiched between plausibly substantive policy debate, that line, along with her focussed group schtick that “the only number Boris is interested in is Number 10” dominated every headline and highlight real.

That remains (did you see what I did there?) regrettable, for in that debate – at least in the section on immigration – something genuinely worth remembering now, nearly 10 years on, can still be found. It’s the bit that comes from Boris himself – that “there’s gotta be democratic consent for the scale of the flows that we’re seeing and at the moment it’s corrosive of trust in democracy”.

At the time Boris came out with that, net migration in the twelve-months prior had been some 321,000 and was about 80 per cent European. 48 per cent, yes that number, thought immigration was amongst the top two most important issues, its second highest peak ever, making it the key issue, ahead and easily so of both the NHS and the economy and somewhere between 65 and 70 per cent of the public wanted a sharp reduction in numbers.

UKIP was polling at 20 per cent. He was right then that there was no democratic consent neither actively as expressed in polling nor historic – the Conservatives had after all won the election the year prior on a promise to return migration numbers to the tens of thousands.

The Boris that said that appeared to understand something quite fundamental – that people were unhappy and that said unhappiness was not good for democracy. When later in that debate, the same Boris said that “a city the size of Newcastle arriving every year” needed to be sorted out, one could be forgiven for thinking ‘sort it out’ meant reducing numbers to a Carlisle quantity and not replacing Newcastle with Birmingham and yet Birmingham is what he brought.

The details should largely be familiar to readers – immigration of 1.27 million people in 2023, only 10 per cent of which was European, combined with obvious exploitation of a hideously designed system with the average Zimbabwean care home worker bringing over ten dependents amidst the creation of a defacto deliveroo visa.

Doing all that would be one thing – had the people voted for it – yet to do it after a referendum where the core issue ultimately was border control was as Boris-ancien might term it “utterly corrosive”.

What is most remarkable though, and what demonstrates better than anything else the schtick about ‘none so blind as those who refuse to see’, was Johnson’s interview last week with Harry Cole. No acceptance of reality or his role in it, outright denying the data behind the graph presented to him, before insisting that any increase was just students returning from Covid and Ukrainians to whom none could object.

On the same day as said interview, YouGov released two polls. The first one an opinion poll fed into an MRP – the multilevel regression and post stratification model that has become the gold standard for predicting election results – that yielded 311 Reform MPs and the Tories just 45. The second a poll on the public’s views of Indefinite Leave to Remain – the policy that grants anyone resident in the UK for five years permanent residence – with a plurality for abolition.

They are polls that ten years ago – or on say June 9th 2016 – nobody would have imagined possible, and they are polls whose outcomes were brought about by Boris Johnson and yet he has no framework for that.

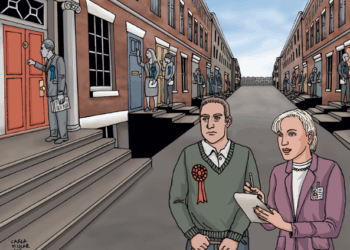

It was the latest example of what the FT profiled earlier in the week – the representation gap captured in a simple chart.

“Immigrants should be required to adapt to the customs of the country” asked to both the public and politicians in six European countries – in Portugal 18 per cent of politicians agree, 72 per cent of the public. In Germany 33 per cent and 75 per cent respectively, and in the UK 47 per cent and 87 per cent.

In each country a huge double digit gap with the sole exception of Denmark where 64 per cent of politicians agreed v 61 per cent of the public. The country of the ‘consensual closing’ has seen the full integration of migration control into mainstream politicians’ talking points, and more importantly policy practice, with an according minimisation of the right-populist Danish People’s Party from 2nd in 2015 to 7th or 8th on current polling.

That representation gap is I think all you need to explain Reform UK. It was a party made by the Leave campaign and it was made in the disconnect inside of that campaign between its leadership – campaigning and then implementing the so-called vindaloo visa – and its voters pleading for restriction.

That same article though touched upon something that ought not be neglected. A new political science paper experimenting with party positioning on migration and how voters respond.

In that paper they do something relatively simple – ask voters their position (0 to 10) on immigration and vaguely where they believe the political parties are before exposing them to a differing position of where the mainstream conservative CDU/CSU is (anywhere from 4 to 7 with 0 being pro-active facilitation of migration).

From it they find what might be the most important result of any political science paper published this year – that for every one point the CDU’s policy was perceived as more right-wing on the issue, and thus the representation gap smaller, the AfD’s vote share fell by 6-7 percentage points.Taken to its maximum it would send the AfD from 21 per cent to the electoral threshold of 5.

It’s a result that should give the Tories some comfort but that comes with one precondition – that you cannot have Boris nor his shadow driving you home.

![Donald Trump Slams Chicago Leaders After Train Attack Leaves Woman Critically Burned [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Trump-Torches-Powell-at-Investment-Forum-Presses-Scott-Bessent-to-350x250.jpg)