Andrew Willshire is founder of the independent strategic analytics consultancy Diametrical Ltd.

Although sympathy for the Conservative Party is in short supply, most commentators recognise that the job that Kemi Badenoch is faced with is particularly tough. The conventional framing of the Tories’ current predicament is that they are being squeezed by Reform on one side and the Liberal Democrats on the other, and you can’t attract more of one without repelling some of the other.

But there is a significant other constituency to lavish some attention on that has been largely ignored over the last year – the number of voters who just stayed at home. Let’s look at the data.

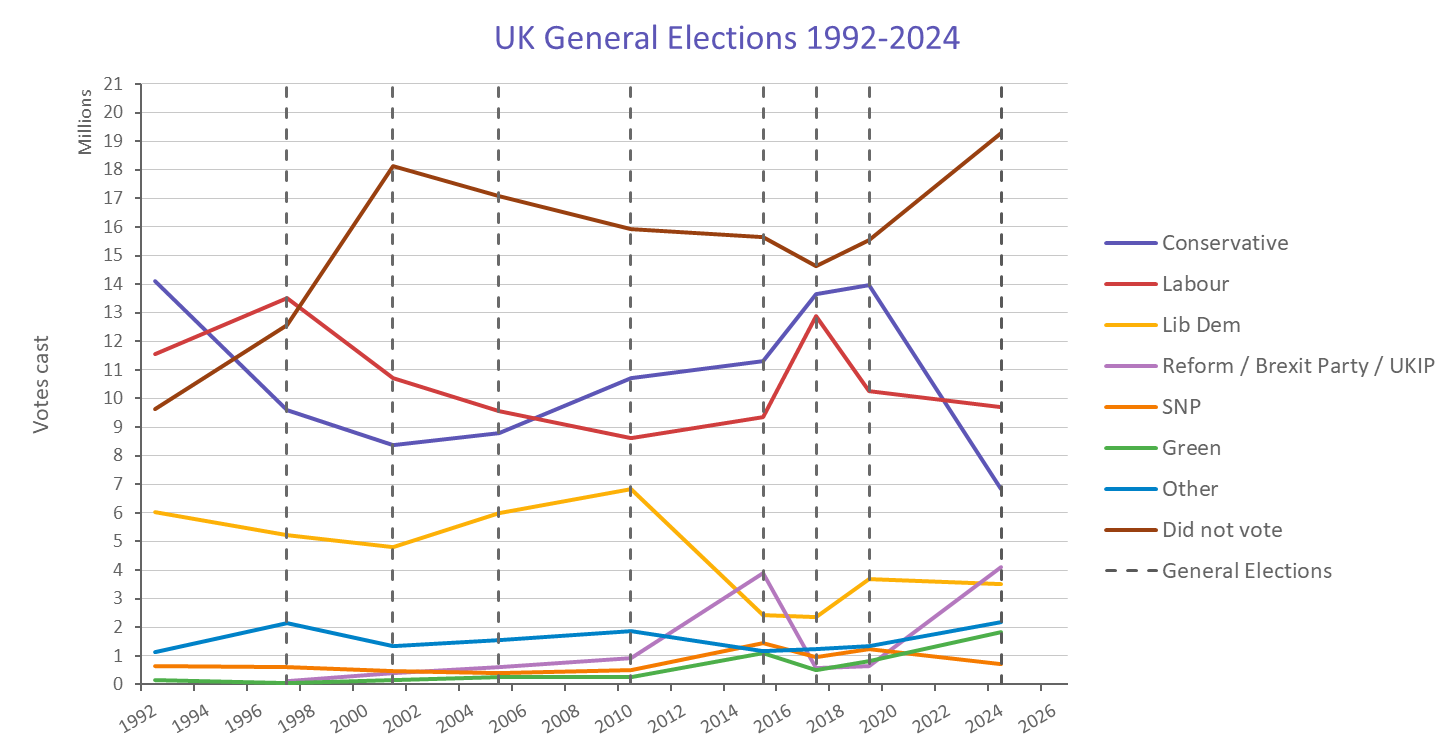

The first thing to note is that both Labour and the Liberal Democrats had fewer votes cast for them in aggregate than in 2019. Sir Keir Starmer’s “loveless landslide” is well-known, but the Lib Dems are similarly unloved, never having convincingly recovered support since the coalition years.

In fact, 2024 was the first election since 2001 that the three largest parties all lost voters. But at least in 2001, it was apathy born of broad contentment with politics, as opposed to general despair.

Reform obviously did well, and despite only gaining around ten per cent more votes than UKIP did in the 2015, it was enough to cost the Tories the election. The Greens are back on the rise after their members’ flirtation with the Magic Grandpa in 2017 and 2019, while the SNP slumped to a vote total of just half their 2015 post-Indyref zenith.

However, the difference between 2019 and 2024 is overwhelmingly a story of the Tory collapse, losing a clear 51 per cent of their previous voters, or 7.1m people. Taken in aggregate, while there will have been some switching in all directions, 3.4m voters switched to Reform but a colossal 3.7m just stayed at home.

Some may consider it a stretch to think that all of those are ex-Conservatives. But left-wingers unenthused by Starmer had the Green party as an option as well as the Lib Dems. It makes more sense to think that the lapsed voter is most likely to have voted Conservative in 2019 but couldn’t bring themselves to vote for any of the other parties; they just stayed at home in disgust or disappointment at how the Tories behaved in office.

Crucially, they chose not to back Reform, even as a protest vote. What might be the effect of attracting some of them back to the Conservative Party?

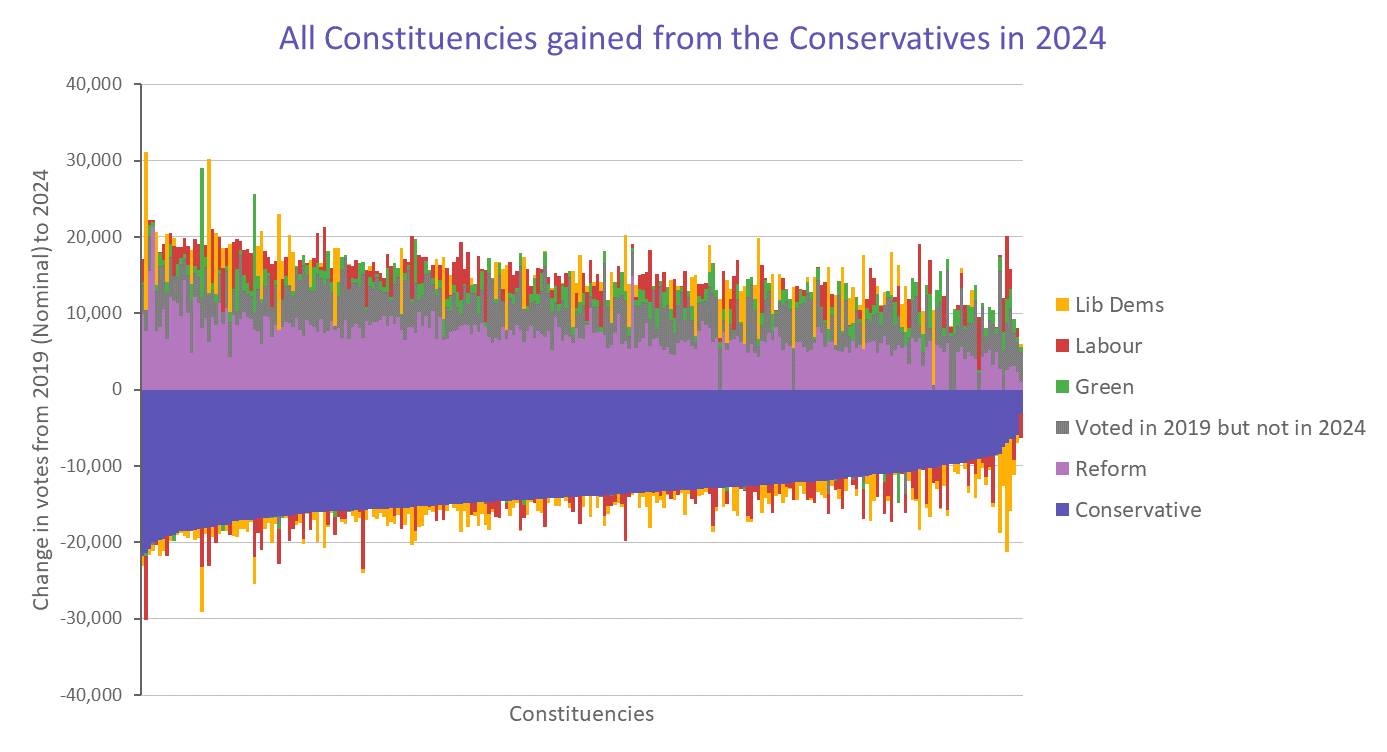

Using the data from the 2024 election and comparing it to a back-projected 2019 election on the same boundaries, we can investigate the changes in vote share that took place at a constituency level. The following chart shows these changes in the 252 seats that the Conservatives lost in 2024.

The most obvious change is the 3.5m votes that the Tories lost across these seats. Reform gained almost 1.8m votes (gifting about 145 seats to Labour in the process), but there were also around 1.1m voters who just stayed at home. On top of that, there was a good deal of tactical voting as Labour, the Greens and the Lib Dems swapped voters about, but gaining only around 590k votes in aggregate.

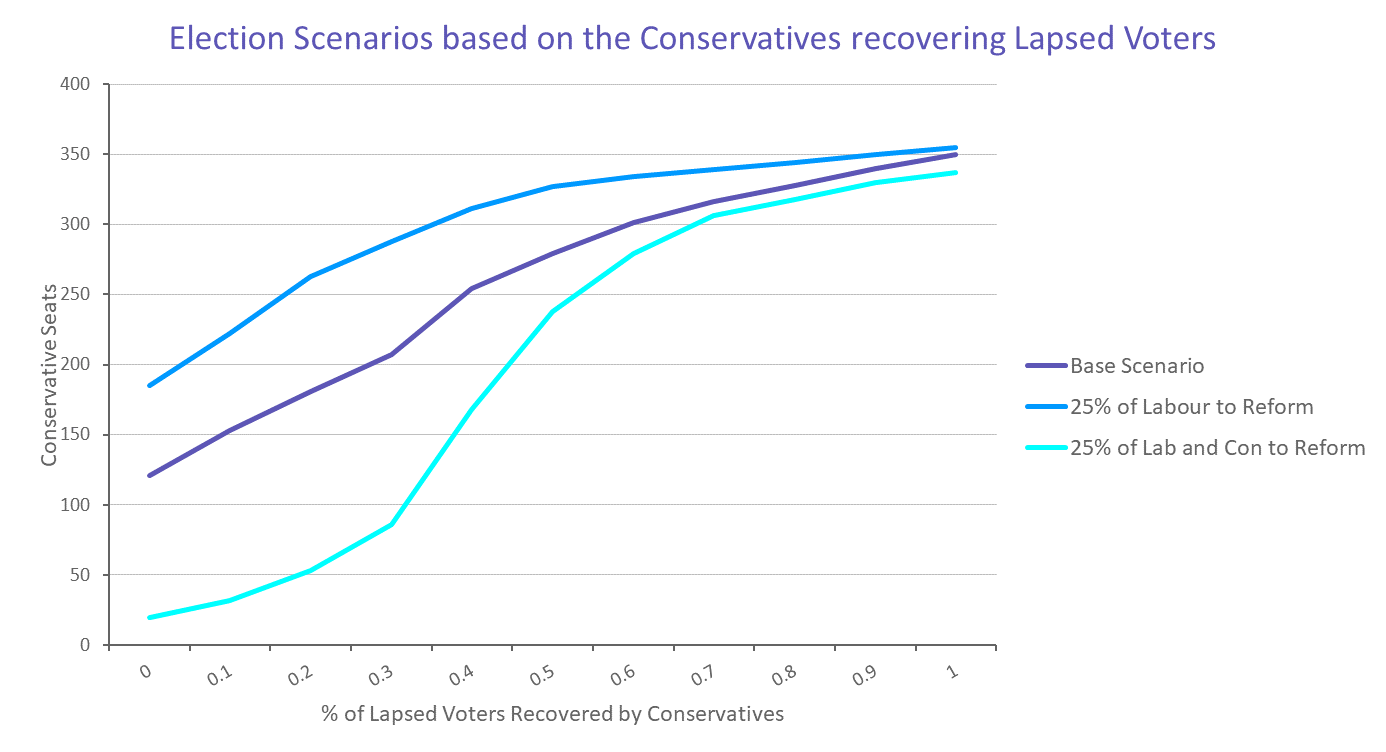

Although it might be simple to conclude that the only way to win power again is to target Reform voters, there is an alternative. Let’s look at three scenarios:

- A base scenario of the Conservatives recovering a proportion of lapsed voters in only the seats that they previously held but with no other changes to the 2024 votes cast;

- The same as the base scenario but with 25 per cent of Labour’s 2024 vote going to Reform;

- The same as the base scenario but with 25 per cent of both Labour and Conservative 2024 votes going to Reform.

In the base scenario, winning back only 50 per cent of lapsed voters would result in Labour and the Conservatives tying in the Commons with 279 seats each with the Lib Dems reduced to 54, and Reform with a single seat. Clearly a Lib-Lab pact would be the outcome.

However, that scenario supposes that Labour keeps their entire 2024 voter base, something that seems quite unlikely at this moment given the public mood. In the scenario where 25 per cent of Labour’s 2024 voters move to Reform, then the Tories could be the largest party in the Commons by regaining as few as 20 per cent of lapsed voters. Regaining 50 per cent would give them an outright majority, with 327 seats against 180 Labour, 54 Lib Dem and 42 Reform.

The final scenario is that, as well as Labour losing votes to Reform, the Conservatives also lose 25 per cent of their 2024 support to Reform but do succeed in winning back some of the lapsed voters.

If they were unable to win any back, then they could be reduced to a rump of just 20 seats. But again, the magic number is 50 per cent: winning back half of lapsed voters in this scenario would make the Conservatives the largest party with 238 MPs, with Labour on 177, the Lib Dems on 72, and Reform on 114. In this case, a post-election Conservative-Reform pact would be inevitable.

So what does this tell us? First, it shows that the Conservative Party has options beside running to the right. While Reform have taken a large chunk out of the Tory vote, they are now proceeding to eat Labour alive in their socially-conservative heartlands, while the Greens and the Corbyn-Sultana project will likely pull in a significant number of progressives.

In a situation where Labour starts to haemorrhage voters, the Tories could start winning significant numbers of seats even at their current vote tally. If they can prove themselves again to be a convincing party of government, and attract back a decent proportion of their lapsed voters, the road to at least being the largest party in the Commons opens up.

Second, for all their troubles, the Conservatives may actually have better medium-term prospects than Labour. If that sounds strange in light of the polls then consider that opinion polling routinely underestimates the Conservative vote share and overestimates Labour, and has done for years. In every election, this seems to take pollsters by surprise, yet they never fix it.

Fundamentally, there are at least one million more people in the country who have voted Conservative at some point than have ever voted Labour, and people are remarkably consistent in voting behaviour. There appears to be a deep reserve of Conservative-inclined voters who turn up when they feel it’s necessary (e.g., 1992, 2017, 2019); when faced with Starmer and Nigel Farage as alternatives in 2029, they may well show up again.

It is vital, however, that they look like a potential party of government, which means ending the constant appearance of division. If Tory MPs are able to put aside their regicidal tendencies, their chances of forming the next government are much higher than many observers suppose.

![Gavin Newsom Threatens to 'Punch These Sons of B*thces in the Mouth' [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Gavin-Newsom-Threatens-to-Punch-These-Sons-of-Bthces-in-350x250.jpg)

![ICE Arrests Illegal Alien Influencer During Her Livestream in Los Angeles: ‘You Bet We Did’ [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/ICE-Arrests-Illegal-Alien-Influencer-During-Her-Livestream-in-Los-350x250.jpg)