Anthony Breach is an associate director at Centre for Cities, where he leads on housing, planning and devolution.

The British public is not happy about the economy, and they’ve got a point. Sluggish growth since the General Election and a slow recovery from the 2008 financial crisis means it has been over two decades since voters saw big improvements to their living standards. The average urban resident saw their disposable income after inflation increase just 2 per cent from 2013 to 2023, compared to 27 per cent from 1998 to 2008.

The Government has pledged that economic growth is its number one mission, but the public’s focus on ‘cost of living’ has pushed Number 10 to promise action on prices, bills, and household costs.

The politics is understandable, but carries risks. Action on the cost of living can only ever be temporary and zero-sum – without growing the economic pie, cutting it up differently just means we all get small slices.

Economic growth is the only way to improve the public’s disposable incomes, as we cannot consume more than what we produce. No party can credibly claim to have an answer to the public’s dissatisfaction with British politics without a plan to increase incomes through growth.

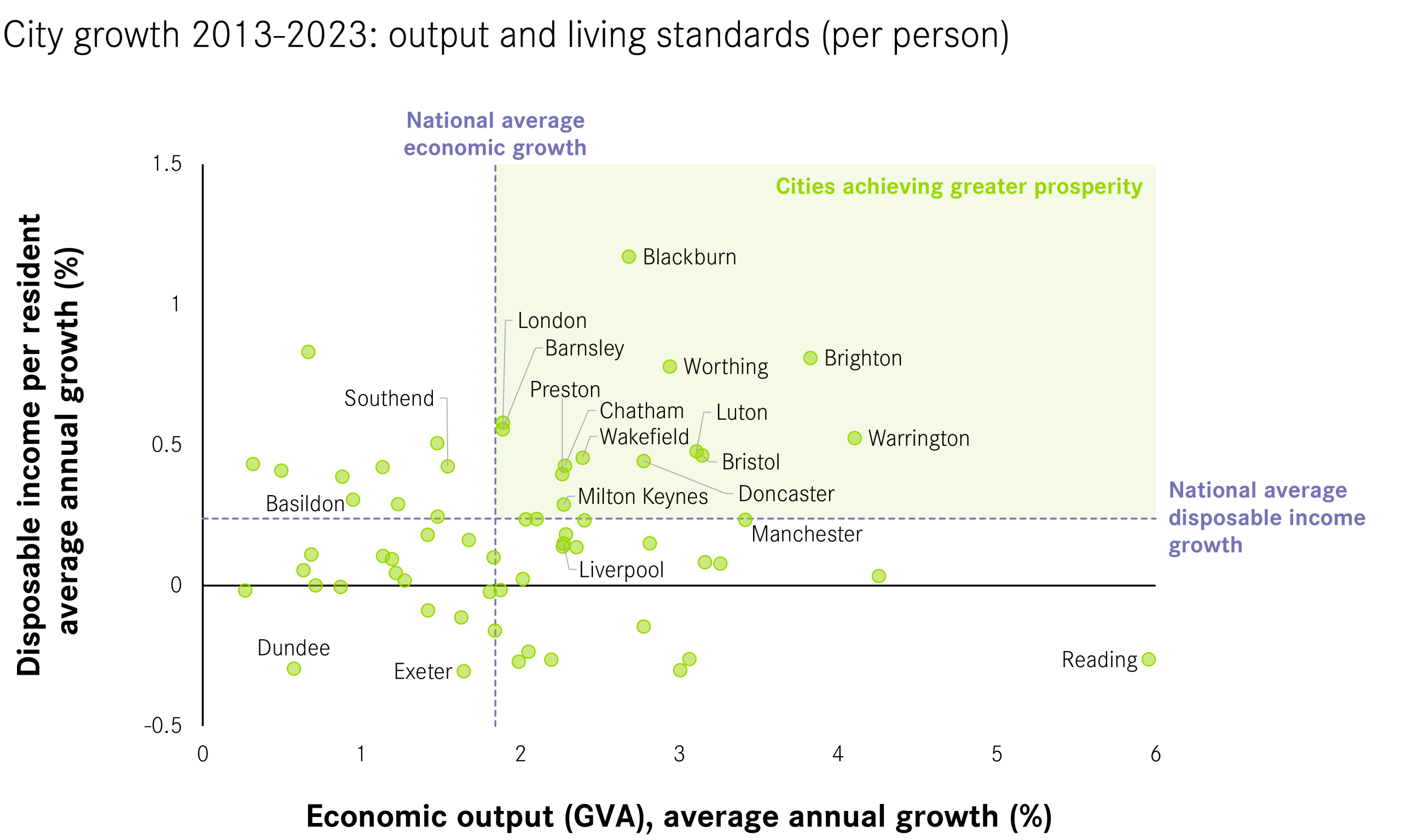

Some of the answers to this problem can be found in the previous period of Conservative government. As Cities Outlook 2026 shows, from 1998 to 2008, average economic and disposable incomes each grew by around 3 per cent each year. From 2013 to 2023, the economy grew by around 2 per cent a year – but disposable incomes only grew by 0.1 per cent per year.

In other words, economic growth and income growth have been disconnected. Reconnecting the economy to living standards and then securing higher economic growth is how to translate Britain’s strengths into better living standards for everyone.

Urban Britain has to be the heart of this strategy, for two reasons.

First, cities are where 54 per cent of the population and 63 per cent of the economy are located. Without a more prosperous urban Britain, there’s no path to either a stronger national economy, or a majority in Parliament.

Second, as Figure 1 from Cities Outlook 2026 shows, some urban areas bucked the national trend and secured significant economic and income growth.

Crucially, these cities were not just the already affluent – places as varied as Warrington, Bristol, and Doncaster offer three lessons to national leaders on what needs to be done to reconnect the economy to living standards.

The first lesson is a strong and diverse private sector.

So-called ‘tradable’ businesses that sell to wider markets – such as software, marketing and manufacturing – bring money into the local economy and support incomes. Barnsley has seen incomes grow twice as fast as the rest of the country, as the council has both satisfied growing demand for the logistics industries and successfully pushed for more jobs in highly skilled professional services on the cutting-edge of technology.

The second lesson is improving access to the labour market.

Low local incomes are often driven by low employment, and in cities like Liverpool, interventions to get people into work and skills training have led to rapid reductions in income deprivation.

But transport matters too, especially in the big cities.

Residents of Manchester neighbourhoods well-connected by bus and rail were twice as likely to see reduced deprivation as those who are not. This is because of their access to Manchester’s booming city centre, which has seen the share of jobs in highly skilled professional services catch up to London city centre over the past decade.

The third lesson is reducing growth constraints, especially housing.

As the biggest component of household budgets and an essential spend, high housing costs have a big effect on disposable incomes. In cities like Brighton, rapid economic growth has been blunted by high housing costs, with low supply the result of England’s restrictive planning system and overly-tight council boundaries.

Achieving more of these success stories across the country align with the politics too. Cameron with the Northern Powerhouse and Johnson with Levelling Up secured the only Conservative majorities since 1992. Successive Conservative governments’ support for devolution to the metro mayors has been crucial and is a record to both be proud of and build upon.

If we want the country to feel growth and beat the cost of living crisis, urban Britain shows the way to do it – by adding more high-wage, cutting-edge jobs in urban centres, improving access to them, and reducing housing costs for people who live near them.

![Keith Ellison Caught Promising to Fight State Agencies for Somali Fraudsters [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Keith-Ellison-Caught-Promising-to-Fight-State-Agencies-for-Somali-350x250.jpg)