Editor’s Note: This is the eighth of nine episodes of Scott McKay’s forthcoming novel Blockbusters, offered in serial form as an exclusive to The American Spectator readers in advance of its publication in October. Blockbusters is the third novel in the Mike Holman series; the first two, King of the Jungle and From Hellmarsh With Love, were also serialized at The American Spectator prior to book publication.

Mike Holman, the protagonist in the series, is an independent journalist who’s been called The World’s Greatest Newsman. But in Blockbusters, he’s literally going Hollywood — choosing to head up a campaign chiefly funded by Pierce Polk, Mike’s long-time friend and one of the richest men in the world, to reform and save American and Western culture.

Starting with an attempt to fix the film and TV business.

In Episode 7, Mike’s group has shaken off some initial trouble and is finding its way toward disrupting the corporate entertainment world, but trouble from across the Pacific has begun to rear its head…

Jupiter, Florida – June 19, 2025

XYZ Sidney released one of its two summer blockbusters on June 12. It was a kids’ movie — sort of. The Tigresses was about a junior high girls’ basketball team that wins the city championship, but with a twist: the whole team is a bunch of biological males. The movie was set up as though it were an underdog story, but strangely, it wasn’t all that believable.

It was as though the folks at Sidney watched Ladyballers and decided to remake it not as a satirical comedy but instead as a heartwarming summer blockbuster.

And despite its $100 million production budget and an additional $100 million marketing spend, including an absolute deluge of house ads Sidney dumped on their four sports networks promoting this thing, it bombed.

Really badly.

The Tigresses did only $3 million in the opening weekend. Then there was the resulting nationwide boycott of Sidney’s two theme parks which ended up being pretty successful; attendance fell off by fifty percent year-over-year in the 30 days following the film’s release. On our Zoom call, Numakin was joking that XYZ Sidney’s stock was shorting itself.

“These people don’t deserve to run a great company like that,” he said.

“I don’t think they’ll run it for much longer,” said Stan.

But Numakin had also sent, by private courier, a thumb drive. I opened the zip file that was on it, and I couldn’t make much of it. But Gardocki, who had just made partner at the PGFI Equity Fund — it was now Stan, Gardocki, and me — could. He said these were confidential reports leaked from Sidney’s accounting department, and they were “problematic.”

“It looks like they’ve been inflating revenues on their film properties and streaming platform,” he said. “By a lot.”

“And what is a lot?” I asked him.

“Like four billion bucks and change over the last three years.”

So I asked Bernie if he wanted Holman Media to break that scandal.

“Not yet,” he said. “But soon.”

Then I had to head home and pack, because PJ and I were off to Baton Rouge to see the folks at Surge Vision now that the paperwork was all signed and PGFI was assuming control of the place.

Except when I got back to the house, it was clear she wasn’t going anywhere.

“I have your bags all packed,” she said, her arms around me and a big kiss planted on my cheek. “But you’re on your own.”

“But PJ,” I said, “you’d really like this place. There’s a cool vibe there, and it’s a fun town… are you sure you just want to stay here?”

“I don’t have much of an appetite for traveling or meeting new people right now. I’m three and a half months pregnant, I’ve got this beautiful house, and this funny dog who’s finally learning not to pee inside or bite everything, and I’ve got my neighborhood friends, and that genealogy project I’m working on…”

PJ was a genealogy nerd. She’d traced her family, my family, Kaylee’s family, Melissa’s family, and now Trina Lynch had her doing their family. How she could root through all those records without collapsing from boredom, I have no idea, but it was a passion of hers.

“My wife, the former Secret Service badass, is now an old woman,” I said. “Who knew?”

“You’re funny. But I’m not coming with you. And you can’t shame me into it.”

“I just thought you’d want to come along for the ride,” I said. “Like this would be a project you’d want to fit into.”

“It’s your project,” she said. “Look, what I learned in the Secret Service is you protect your principal, but while you’ll want to be friendly to him, or her, you aren’t a participant in what they’re doing. That’s kind of like what this is. I don’t need to be involved in your stuff. I want to be a respite and a safe space away from it. That’s the role I want. OK? I’m keeping this house beautiful and clean and cozy, I’m a hug and a kiss whenever you want one, there’s a hot meal in the kitchen for the asking, and I’m gonna bear you as many children as you can handle. That’s it. You have Melissa to be your assistant. You don’t need me for that.”

“OK,” I said.

What else was I going to say? She’d just declared herself to be the perfect wife, and all I had to do was not drag her on a work trip.

Back in early May, PJ had diagnosed me perfectly. She said that getting stuck in Belmarsh Prison last year, for only a few weeks as it turned out, but at the time it looked like it could have been years, changed me in a significant way. It energized me. It made me want to do big things with the time I had left. Belmarsh was why I dumped out of Holman Media to do PGFI.

Of course, getting locked up over there simply for doing podcast interviews the government didn’t like also opened a window into what America’s future could be without a major cultural correction, so there was an intellectual reason for the change as well as the psychological one PJ had identified.

But her reaction, she said, to having me in Belmarsh while she was keeping vigil in London and pleading with the Stormer government to let me out was the opposite. She couldn’t wait to get me down here in Jupiter so we could live the most comfortable, upbeat life possible. That was her mechanism.

And she kept telling me it was OK for us to respond differently.

“Look,” she said, when she was initially explaining her position, “I’ll explain this to you in terms you’ll understand. You and I are like Michael Douglas and Kathleen Turner in Romancing the Stone. Our relationship was actually built on adventure and danger. Right? Getting shot at in Guyana? Belmarsh? It’s a lot like that movie.”

“You dredged up an old movie reference for me,” I said. “I don’t think I could love you one bit more than I do right now.”

“OK, but as good as Romancing the Stone was, Jewel of the Nile was… less so. Why? Because shared suffering is good for building relationships, but maybe not so good for sustaining them. I’m not interested in sharing adventures with you. I want to share a life with you. That means giving you freedom to have the adventures you need to have.”

So when she bailed out of the Baton Rouge trip, I wasn’t about to fight her on that. I just kissed her and made her drive me to the airport, and then kissed her again when she dropped me off.

“I’ll see you next week,” she said. “Call me whenever.”

“So this is going to be a bit different model than you guys are used to,” I said, “but what I can say is that it’s something we’re trying at Belmarsh Entertainment, and so far it’s really taking off.”

The room was quiet, and I could tell that the Surge Vision folks were nervous. The word had gotten around that we were going to lay off a whole host of the employees there, though Grant couldn’t tell me how that rumor had started. It wasn’t my intention to do that at all.

“Here’s the model we’ve set up in Corpus Christi: everybody there is a filmmaker, and we’re treating them as such. Our folks over there are crewing one project, editing another, writing something else, and even serving as an extra on a fourth thing. It’s a collaboration, and we’ve set up a system whereby there’s a salary up front and a back end behind it based on level of involvement within those projects. Sure, we’re picking people up on a per-project basis, but there’s a core group of associates, and within that group, everybody works on everybody’s projects. And that’s what we want to do here.”

“You mean I’d get to direct?” said Jeff, the camera guy.

“If that’s what you want, yeah,” said Grant. “Y’all know about CASTR, which is PGFI’s filmmaking app…”

“It’s gonna put us all out of our jobs!” said an old guy whose name, I later found out, was George Gurdy; he was a film editor.

“Actually, no,” I said. “It won’t. But it will change how you do your job.”

“Yeah, but if you just get AI to make movies, you don’t need people to do it.”

“You’ll always need people,” said Hank, who’d flown in from Austin for this meeting. “Believe me, I’ve played around with CASTR as much as anybody, and let me tell you — without human direction, what AI will create is not going to outpace old-school filmmaking.”

That seemed to quiet old George down.

“The thing is,” I said, “we’re going to be using CASTR to simplify film production. But that doesn’t mean a smaller operation. It means more and better production from the same operation. What we want to do is flood the zone with great film and TV, which isn’t shackled with stupid Hollywood rules or run through the big-studio bottleneck. What we’re building will be a distribution system that makes it really easy for people to find great art, and with CASTR, we’ll have a greater ability to translate the great ideas in our heads into something concrete. The execution of those ideas has always been the bottleneck, right? You have a beautiful painting in your head, but your fingers can’t deliver it to the canvas.

“Well, with this, those ideas can be brought to a movie or TV screen like it hasn’t been possible up until now. The beauty of this app is its ability to interface with the AI on a level that hasn’t been done before.”

“So what are you telling us?” George demanded.

“Let me ask you this,” I said. “Why did you get into the film business?”

“I wanted to be the next Frank Capra.”

“Right. I figured you’d say that. Rod Nachman, who’s the CEO over at Belmarsh, has this quote he says all the time. ‘Nobody grew up wanting to be a best boy or a key grip.’”

There was laughter in the room.

“You all want to make movies! That’s why you’re here. But hey, not everybody can act, and it’s hard to get a gig as a director. Writers often starve to death. But if you love movies or TV and you want to be in the business, then get a job on the set, right?”

I saw a bunch of nods.

“So the beauty of CASTR is that everybody here gets access to it and you’re encouraged to make your own movies with it.”

“You mean Surge will release something I make that’s all AI?” said a twenty-something woman with a neck tattoo.

“I mean, there are going to be some guidelines we’ll operate within, like we don’t want to do hard-core porn or senseless violence or satanic stuff, things like that, but otherwise yes,” I said. “In fact, one guy at Belmarsh has a concept for a kids’ cartoon show, kinda like the old Fat Albert cartoons Bill Cosby did back in the day, and we did the whole thing in CASTR. We have the whole first season done. Derrick did all the voiceovers himself, and we washed them through the app and you’d never know they’re all him.”

“I’ve watched the pilot episode,” said Grant. “It’s just about the greatest thing you’ve ever seen.”

“But he didn’t do it alone,” I said. “There were a half-dozen people who pitched in with editing, redesign, some script rewrites, and other things. But from soup to nuts, that first season of his show, all 12 of the 45-minute episodes, went from a screenplay to in the can in about a month.”

There were murmurs in the room.

“So as you can see,” said Grant, “there’s a whole different way of doing things that can be an awesome creative opportunity. Everybody here, if you’re willing to fly your freak flag and come up with ideas and be great, can fulfill all the dreams you’ve ever had about show business.”

“I’m too old for all that,” said George. “You’re saying you’re gonna leave me behind, and lots of us here, too.”

“Nobody is going to be out of a job,” said Grant. “George, we’ll still need a film editor.”

After the presentation, which was received positively by probably three-quarters of the Surge Vision folks, I noticed that this guy George pigeonholed Grant, and he was giving him eleven tons of shit about the new vision. I was going to go over there and step in, but I couldn’t; Hank and I were too busy getting mobbed by the rest of the Surge Vision folks. They all had cool ideas for movies they wanted to try out, and they were asking for permission.

“We’re going to bring the CASTR folks in next week and do training for everybody,” Hank assured them.

“And when you’ve learned it,” I said, “it’ll be on you guys to develop it. It’s a tool, and that means we don’t really know all the ways it can be used yet. Eventually, it’ll be publicly available. For now, it’s ours. Let’s maximize it.”

They all seemed to love that.

But when Grant and I were at lunch a little later, he said he saw some bumpy traveling ahead.

“Why?” I asked.

“Because when IATSE, SAG-AFTRA, and WGA get hold of what we’re doing, they’re going to blacklist everything PGFI does.”

He was talking about the three unions that controlled everything in Hollywood, or at least everything Blondheim didn’t.

“We’re here in Louisiana,” I shrugged. “Belmarsh is in Texas. They’re right-to-work states. Who gives a shit about the unions?”

“Writers, directors, and actors do,” he said. “Gonna be hard to get big-name talent for these productions.”

“So we’ll create our own big-name talent. Nobody knew who Johnathan Roumie was until he played Jesus in The Chosen. Now look at him.”

“Yeah, but that takes longer and it’s expensive. Get somebody who’s proven at the box office, and it’s easier to make a winner.”

“Grant, come on. When is the last time Surge Vision had proven box office people starring in your productions?”

“I thought the point was that we’d break out of the B-movie mold.”

“Here’s my thing: I want to work with people who aren’t part of that celebrity asshole culture. I met some while I was out there earlier this year, and I got a lot of back-channel communications from folks who told me they’d love to work with us, but they needed to see that we were serious. I think getting blacklisted might smoke some of those guys out and move them to our side.”

“What, like these mythical Hollywood conservatives?”

“They’re not mythical. They’re just hiding. I want to make it so they can be who they are and still work in showbiz.”

“So you mean to build an entirely different institution,” Grant said. “Like a complete alt-Hollywood altogether.”

“Stop thinking in the box you’ve been thinking in,” I said. “We’re going to blow open this process and rebuild it for the 21st century. That’s what your job is going forward. If the unions don’t like it, then let them get run over when we’re out there making more and better IP, and our people are making more money doing it. Especially when everything we’re working on comes to fruition.”

“OK, fine,” Grant said. “I’ll trust you. And I’ll rally the troops.”

And then he insisted that I join him because a friend of his was throwing a giant watch party for the College World Series finals that LSU was playing in.

“I thought you went to Ole Miss,” I said. “Don’t you people hate LSU?”

“You can’t hate LSU when you live in Baton Rouge,” he said. “It’s not safe.”

While I was in Baton Rouge, consequential things were happening in Washington. The same day Grant and I were pitching the Surge people on the idea they’d all be able to turn into little Kubricks and Spielbergs, Bernard Numakin was at the White House announcing the creation of the Bald Eagle U.S. Sovereign Wealth Fund.

This thing was a joint venture of the Treasury, Commerce, and Interior Departments, along with a coalition of private investors. Congress had inserted language in a big budget reconciliation bill they’d passed authorizing creation of the fund and providing tax breaks to private investors who would throw money into it.

It was a bit of a strange animal, this species of the Bald Eagle. Nominally, it was charged with an orderly selloff of U.S. government land assets — a lot of government property in urban and suburban areas, a good bit of land in the West which wasn’t designated as part of the National Park system, and a whole bunch of mineral rights.

But it was also authorized to participate in market investments. And the Bald Eagle was charged with investing tariff revenues for the government, which made for a really interesting plan that Numakin outlined — the fund was going to finance infrastructure projects around the country where those could be seen to generate revenue.

Bridges and tunnels. Airports. River and harbor dredging. The real infrastructure stuff that state and local governments, begging for funding from the feds, had gotten so miserably slow in producing. Numakin outlined that the Bald Eagle was going to be a one-stop shop for those projects so that they could be financed not by the politics of the appropriations process but as investments for the public good, vetted through their potential for generating a return.

They were moving a whole bunch of stuff out of the federal budget. Now, there was revenue coming out as well, but the point was that the sovereign wealth fund would be paying down the national debt with a portion of its profits to match the level of federal ownership of the fund. And that portion, initially, was 75 percent, as the Bald Eagle’s initial capitalization of $400 billion was $100 billion in private capital and $300 billion in property and dedicated tariff and mineral royalty revenue.

This threw a lot of the free market libertarian crowd into histrionics, and cries of “socialism!” and “fascist economics!” went up from some of the usual quarters. But there was generally bipartisan support for the creation of the Bald Eagle Fund, and specifically there was a great deal of public support for a mechanism by which the national debt might be paid down; the Congressional Budget Office put out a report, amid the negotiations over the budget reconciliation bill, that the deficit would stay at $2 trillion for the next decade if the bill passed. There were lots of arguments over whether anybody at the CBO knew a damn thing about what the budget deficit would be, and it came out that almost four-fifths of everybody at CBO was a registered Democrat, which alone called into question whether any of that scoring was real, but nevertheless the public accepted that Congress wasn’t going to solve the deficits and debt.

So somebody else had to. And Numakin’s project was the only game in town. It was hard to argue against Bald Eagle.

I’d been on a call with Numakin and Pierce talking about Shining Star, and it turned out that Numakin wanted the get the Bald Eagle involved.

“If you’re serious about making your telecom network into a public utility,” Numakin was telling Pierce, “where it’s a regulated monopoly pulling a fixed profit margin and providing a truly open platform for communications, media, and the arts, then we can invest with you.”

“OK, so we all understand each other,” I said, “what we’re contemplating is capturing practically everything the corporate media has in space, most of the vehicles for connectivity, and putting them into one national comms infrastructure network that the FCC, I guess, would regulate as a monopoly.”

“Yes,” said Numakin. “And the Bald Eagle fund would have a piece of that set profit, which would be used principally to pay down the principal on the national debt.”

“Meaning that the government would now have a financial interest in incentivizing the creation of commercially successful IP,” Pierce mused, “because the more content creators are operating on the Shining Star network and the larger the audiences they would attract, the better the revenues would be.”

“That’s correct,” Numakin said. “We’re doing this as a vehicle for a cultural renaissance, and also as a moneymaking proposition. Neither the federal government nor the Bald Eagle fund will participate in or fund content creation on the network, so there is no threat of, or plan for, rigging of the market. This isn’t a PBS or NPR type of situation. We are merely participating in a scheme to give the American people an open communications platform where the only gatekeepers are those the consumers choose to hire for themselves.”

“Taking the best parts of the internet and applying them to broadcast media,” I said.

“That’s right, Mike.”

“And our idea for the Blockbusters streaming platform?”

“It’s just one service among many that will access the platform.”

“And when this is announced, it’s going to crash the stock of all of the Big Five, isn’t it?” said Pierce.

“Conceivably, yes.”

“And PGFI and the Bald Eagle Fund will necessarily step in and backstop these stocks so that they don’t lead to a wider market crash,” I said.

“It would be only fair to the small investor to do so,” said Numakin.

“Gosh,” said Pierce. “But this would mean we’d end up having a controlling interest in all of them.”

“Except for BRONY. It being Japanese-owned, and so forth.”

“Can we get away with this?” I asked. “I would think the SEC would lose its mind over such a scheme.”

“Not if what we’re contemplating is a new system which increases public access and transparency and provides for a public benefit.”

“As in, we immediately spin off cable channels, broadcast networks, and film and TV production into separate publicly-traded entities,” said Pierce.

“A process which the Bald Eagle fund would control, as it’s a neutral entity solely focused on retiring the federal debt. Therefore, there would be no favoritism toward one market player over another.”

“So PGFI would sell its shares in the Big Five to Bald Eagle on a… what, promissory note to be paid back out of proceeds from the unwinding?” asked Pierce.

“You have it exactly.”

“This is going to be tied up in court for decades,” I said.

“It depends on how big the emergency is, doesn’t it?”

“There’s going to be an emergency?” asked Pierce.

“There’s always an emergency,” said Bernie with a smile.

And the next day, like clockwork, there was.

Ever since Shri Bundarahman had been forced out as the CEO of Summit Entertainment, the stock had been teetering on the verge of collapse. But on June 10, it finally dived below $10, completing a $5 billion market-cap dump since RedGuard had blocked our takeover play.

Stan had hooked our group in on a Zoom, and he and Gardocki were touting the opportunity to finish our conquest of the company at a discount.

“I don’t think we should,” said Numakin.

“Me neither,” said Pierce.

“Mike,” Stan pleaded, looking at me from across the conference table, “what are we doing?”

“We’re gonna let it go,” I said.

We all knew what that meant, because the Street was full of rumors that Dragon Harvest was going to tender an offer for Summit.

And that’s exactly what happened. They came in at 15 bucks a share and cleaned up a controlling interest in the company.

Trumbull was on the White House lawn not 30 minutes later, howling about the disaster that would come if Summit Entertainment were lost to “Chy-na.”

“Peter Chang, this guy, he sold out his company and his country to the People’s Liberation Army, and now they’re gonna be pumping out Chinese propaganda on our airwaves,” he said. “But I’ve got news for Little Peter. The answer is no. We’re gonna stop it. No sale.”

Trumbull put out an executive order giving Dragon Harvest 30 days to divest itself from Summit.

Chang called a press conference from Dragon Harvest’s new headquarters in San Francisco, accusing Trumbull of “racism” and announcing they were going to court to invalidate Trumbull’s executive order.

And Judge Susie Hong of the United States District Court for the Northern District of California, a Joe Deadhorse appointee, issued an injunction against the Trumbull administration from her bench in San Francisco three hours later.

The whole country threw a fit over the fact that one of America’s most prominent media companies was now in the hands of a foreign adversary, and for the time being, nobody could do anything about it.

Back at the house later, PJ was beside herself.

“I’m so ashamed,” she said. “I’ve been, y’know, estranged from Dad for months, but Mike! I mean, he’s a traitor!”

“Well, I don’t know that I’d go that far,” I said. “When Summit’s movies all quote from Mao’s Little Red Book, or when SBS’s evening news broadcasts start showing happy Taiwanese waving Chinese flags as the tanks parade down the streets, then we can say Peter is a traitor.”

That didn’t go over well.

“Why didn’t you all stop him?” she whined. “You could have bought that company. You bought the movie studio away from him!”

“We have… other plans,” I said.

That didn’t help PJ’s mood.

She’d been largely happy to stay out of the way of PGFI’s exploits, and that was OK by me. After all, if your wife isn’t involved in your work, she can be a respite from work, and PJ was doing a great job of that.

But Peter’s entry into the media game dragged her in, and that was making her miserable. She kept calling her brother Kevin, demanding assurances that this wasn’t what it looked like, and Kevin, who, she came to the conclusion, was plotting his own exit from what had been Chang Pan-Pacific, gave her none.

And Mary, who had flown in from Guyana at the end of May and was staying with us, as I’d asked her to help Morris with the legal aspects of what we were working on, just laughed.

“I know what the other shoe to drop will be,” she said.

Mary was 100 per cent prescient, because the next day, Dragon Harvest America CEO Peter Chang announced the new CEO of Summit Entertainment would be…

…Pamela Farris.

And the new head of Summit Entertainment Studios was…

…Barry Blondheim.

The courts got a little busier after those announcements. There was Mary’s divorce filing, something she’d sworn she would never do. And there was my lawsuit against Blondheim over the Rohypnol.

Jupiter, Florida – August 16, 2025

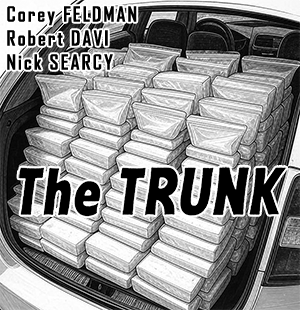

I’ve got to say it – I was wrong about The Trunk.

I thought it was just a B-grade action movie, a re-do of an old Steve McQueen-ish thing. It was built a bit like that, but like Grant said, it was something different.

The Trunk was a comedy. And Feldman, whose character was an ordinary guy working some humdrum middle-management job at a boring tech firm who, thanks to some crazy mixup, found that some big dope dealer had dumped enough Bolivian marching powder in his trunk to get all of California coked to the stars, was actually perfectly cast in the lead role.

He’s fleeing from the more-murderous-than-smart cartel boss, played by Robert Davi, who wants his coke back once he realizes his henchmen have dumped it into the wrong trunk, and you’d think the easy solution would just be to give it to him. But the problem is that the cops know about the coke and they’re following Feldman too — so he’s also fleeing from the police.

And Feldman’s character is a nervous Jervis who’s scared of his shadow, so he’s utterly freaked out for the whole two hours of the movie, which is one crazy and hilarious escape after another. But he manages to survive long enough to figure out how he can avoid getting killed by the cartel or arrested by the cops — which is to drive his Honda Civic off a bridge and fake his own death after he’s managed to record a phone conversation with Davi in which the latter completely incriminates himself.

Which works because his uncle, played by Nick Searcy, is a regional FBI director, and they get him set up in the witness protection program after they fish him out of the river. So he disappears from his boring job and his unsatisfying life, and he starts anew somewhere else. The end.

It was a legitimately entertaining movie. That’s not just my opinion. The Trunk hit theatres at the end of July, and Harnett, who loved it, featured it at the Movie King locations across the country, and it was a smash. It did $20 million in its opening weekend, which was double its budget, and another $15 million the next week. Before it was all said and done, it topped the $50 million mark.

Just in the U.S. The foreign take, as Renzler had promised, was just as good.

Midnightmare and Mekong Moon were basically dogs, but both of them at least made a little money. And Midnightmare did garner a little attention as a cult film; interestingly enough, at Grant’s suggestion, the director made some post-production adjustments, giving it a little bit of a Christian flavor, which actually got the movie some positive reviews on CBN and EWTN as a horror movie churchgoing people could watch.

PJ still said it was dumb. I couldn’t completely disagree with her assessment. But I haven’t been a big horror fan since the first one of the Conjuring movies.

The point being that Surge Vision paid for its acquisition costs in less than two months, and the same financial news channels that had been dumping on me since the spring were now doing 180-degree turns.

Oh, the media attention turned. It was enough to give somebody whiplash.

Jim Cramer noted that we’d now built a media conglomerate of our own that was the hottest thing in the industry, and said it was a crime that nobody could buy stock in us. I got asked about that when I did an interview with Maria Bartiromo, and I said that given the people we’d been competing against in those Big Five acquisition fights, the last thing we’d want to do would be to placate them as potential shareholders in our conglomerate.

“So what’s next?” she asked. “I hear you’re sitting on some bigger offerings at Belmarsh Entertainment.”

“You’re talking about Hoodrats, aren’t you?” I said. “Well, we’ve done a few sneak previews of the first episode at Movie King locations — it’s a thing we’ll be doing; if you’re a Founders’ Club member at Movie King, you can get VIP tickets to the new stuff before it goes public — and the audiences love it. We think it’s going to be a smash hit.”

“It’s controversial, though. Are you worried about a backlash?”

“The people who’d stoke a backlash against Hoodrats are the people who destroyed show business in the first place. It’s not controversial; it’s hilarious. And yes, it makes fun of gay people, just like it makes fun of straight people. Nobody gets out alive, which is why it’s so much fun.”

“But they say it promotes toxic masculinity.”

“Maria, I know you’ve seen it.”

“I have.”

“Do you think it promotes toxic masculinity?”

“No.”

“Well, she said it, ladies and gentlemen!”

Maria laughed.

“The fact is, you can’t make great art without creating detractors,” I said. “And you can’t change the culture without upsetting people who like it the way it is. So yeah — certain people will absolutely hate Hoodrats. But what we’re noticing is that way, way more people absolutely love this series. And when it streams later this year, it will become a cultural sensation in this country.”

When Derrick Washington went on Bill Maher’s show to promote it, he was a bit more direct. Greta Whitmire, the governor of Michigan, told him the show was misogynistic and said she couldn’t believe there were no major female characters, and that the lessons it taught were “anachronistic.”

It was clear she hadn’t watched it. She was rattling off talking points somebody gave her.

“With all due respect, Governor,” Derrick said when Whitmire was finished, “Bitch, please.”

I probably wouldn’t have advised him to say that, but the reaction — that clip went so viral that all by itself it turned Derrick into a star — was absolutely golden. It’s a good thing Nachman locked him up on a seven-year deal for writing, directing, and acting projects, because he otherwise would have been snapped up by the big boys immediately before anybody had even seen the show.

At that point, we hadn’t disclosed when or how Hoodrats was going to get its full release. Blockbusters, the multimedia streaming platform we were putting the finishing touches on, combining the Jump Mobile 5G network, Fling TV, and Shining Star satellite internet system, was still a secret. So the public was just getting teased with a handful of little clips that were being shared on X and YouTube.

Those were intended to be memeable, and that’s exactly what happened. So by the second week of August, Latrell, Luis, Jordan, and Desmond were already household names just because of the funny memes that were all over social media, even though only a few thousand Movie King Founders’ Club members had actually seen an episode.

They were clamoring for Hoodrats, and Stan, Gardocki, and I were giddy.

So was Nachman.

And we were doubly giddy because on August 8, Desert Odyssey had its premiere. Santiago had managed to make that movie in six months, not eight as he promised. And if the speed of the production did any damage to the quality of the film, I sure couldn’t see it; the visuals were sensational, the pacing was awesome, the battle scenes were real as could be, and Parker Stone was absolutely awesome as William Eaton.

The theatres were absolutely packed for Desert Odyssey. It did just over $200 million in the opening weekend. And that was despite the demonstrations outside the theatres.

Oh, yeah.

IATSE protested outside of Desert Odyssey showings, alleging that Belmarsh had “abused” its crews, something nobody had ever complained about. That one, nobody took seriously. But CAIR’s protests alleging that the film was “Islamophobic” because it showed the Barbary Pirates as a bunch of savages and the scumbags running the Barbary coast fortresses like Derna and Tripoli as evil bastards were a little bigger deal.

Not that they negatively affected the movie’s reception. And frankly, this one was something CAIR really should have sat out, because, for example, in Dallas, a pretty muscular CAIR protest of Desert Odyssey led to a large crowd of moviegoers, led by a couple of dozen ex-Marines, literally dragging the protesters out of the parking lot and dumping them on the street. Somebody videoed it and gave it the hashtag #bumsrush when they posted it on X, and the next thing you knew, the CAIR protesters were getting #bumsrushed all over the country.

And that was the end of that.

Things got so weird online that Harnett actually had to deny in an interview that Movie King was recruiting ex-Marines to do the deed. He won the day by pointing out that this was happening at theaters everywhere they were protesting, not just at Movie Kings.

“I’d rather not drag potential customers away from our locations,” he said, “although I will admit these generally aren’t our best potential customers.”

We had a special showing of Desert Odyssey at the White House. All the Marine brass were there, including a bunch of wounded vets from Iraq and Afghanistan. Trumbull gave a great speech, and then he took a picture with Nachman, Santiago, Stone, PJ, and me.

Yes, I managed to get her to go to the White House with me. Even five months pregnant, she couldn’t say no to that one. And the picture of us standing with Donny and Melanie Trumbull, with the president and the first lady both pointing at PJ’s baby bump, went pretty viral, too.

PJ was a little embarrassed by that and swore that was the last public appearance she was going to make for a while. I knew she wouldn’t stick to that, and I was right, but it definitely got harder to get her to go anywhere.

Even though her friends all told her it was the cutest thing they’d ever seen, and she ultimately had to confess that she kinda liked the attention.

And it was hilarious, because the same weekend Desert Odyssey had its premiere, Sidney’s second supposed summer blockbuster, Zombie Invasion, in which a race of zombies from outer space descend on Earth and infect all the humans with zombie-itis or something, hit the theaters. It was Independence Day meets World War Z, and naturally, the zombies only get fought off because the Chinese come up with the vaccine.

That thing was a hot mess of a movie, and Desert Odyssey beat it like a rented mule at the box office.

I got interviewed about that on Laura Ingraham’s show, and I said Santiago had made an utterly great movie, but maybe the reason it was so successful in comparison was that nobody at Sidney was capable of making a movie Americans could stand anymore. That led to an angry press release from Rod Igor saying that Santiago and I were “interlopers” and “first-time lucky,” and that Belmarsh was not a legitimate player in the film industry.

That led Nachman to move up the announcement that Belmarsh was beginning production of Redemption Run just outside of Sioux Falls, and that Iannucci was the show-runner while Gosling was playing the oil company rep and Sydney Sweeney was going to be the Greta Thunberg maniac who gets an education. But we weren’t telling anybody about the plot twist; we just said it was a drama about the competing interests surrounding energy production in rural America.

And Holman Media got to break the news on the falsified film receipt scandal at Sidney the next day. The SEC announced immediately that it was launching an investigation.

With all of that downward pressure, Sidney’s stock just melted. In three days, it fell 44 percent.

When it was over, PGFI Equity’s end of the short came to just under a $14 billion windfall. They were calling it one of the most profitable stock shorts in world history. We ended up reinvesting the proceeds from the short into Sidney, and at the end of the day, we were sitting on just under a 12 percent ownership stake in that company.

Which made four of the Big Five that we had a double-figure stake in.

I actually fought Stan and Gardocki on the Sidney reinvestment, because I thought Movie King was a better place to park our windfall.

“But Mike,” said Stan, “remember: this isn’t just about building a better mousetrap. It’s war. You’ve got to beat the enemy down to his knees to finish this, and that means owning that stock.”

“Yeah, I get that,” I said. “But don’t you think it’s just a matter of time before they start melting away? Especially with the nuke we’re about to drop on these status-quo people.”

“Why take a chance?” said Stan.

Then he looked at Gardocki.

“Conan,” he said in a gruff, unspecified Asian voice, “what is best in life?”

“To crush your enemies, see them paraded before you and to hear the lamentations of their women,” said Trent, in a not-half-bad Schwarzenegger impression.

I couldn’t top that, but I still wasn’t convinced.

Pierce resolved the issue by kicking in a few billion dollars from his own stash to expand the scope of what Harnett was doing once he saw the Movie Kings coming to life. Especially when they agreed on building the mother of all Movie Kings, a sprawling entertainment palace which was going to pair with the Sands Venetian Essequibo hotel and casino already in the works, along the banks of the river across from Liberty Point. Pierce was all fired up about the plans for a gondola system connecting the city with the resort.

That settlement worked for me, because of all the things we’d done, the Movie Kings were what I was most proud of.

Harnett turned out to be just as incredible a corporate CEO in this venue as he was when he ran Ballyard Sports. He was like a Bernie Marcus or Ken Langone for multi-purpose entertainment. Those Movie Kings that were turning over in faster and faster succession around the country were becoming a sensation.

And they all had different attractions to fill the spaces where they’d turned over the screening rooms.

In Saginaw, they had an indoor beach club with a pool and lounge chairs under big lamps that gave off just enough UV light that you could get a slight tan from sitting under them. And there was an island bar in the middle of the pool. The walls and the ceiling were covered with a digital screen wrap that gave off the amazing illusion that you were at a resort in Montego Bay or Nassau.

It was the summer, so that wasn’t quite peak season. But everybody up there noted the genius of the idea that would become obvious once December rolled around in Michigan.

Meanwhile, in Pensacola and Macon, they turned a couple of the bigger theater spaces into mini ski resorts. You could rent skis and boots and ski down a little incline they’d set up with rolling treads. It was like a giant treadmill, and the genius of it was that the surface you were skiing on was set up to mimic the texture of fresh powdered snow. They cranked the temperature in the place down into the 40s, so it felt a little like ski weather. And at the bottom of the little hill was the apres-ski place where there was food and booze. Naturally, the digital screen wrap on the walls and ceilings made you believe you were in Steamboat Springs or Park City, and the floor of the place was, literally, packed snow.

Lots of the Movie Kings had laser tag. There were virtual shooting ranges with skeet shooting. There were rock-climbing clubs with walls that scrolled as you ascended them, so instead of climbing 30 feet, it was more like 600 feet. Most of the Movie Kings had study halls that were tailor-made for homeschoolers to use; they had big screens where they’d show Khan Academy and Prager U stuff, plus documentary films and other things homeschool kids could fit into lesson plans. The homeschool moms loved it; they could leave the kids with the proctors and do the VR spin classes or art-and-wine studios right next door, with the big glass windows in between so you could look in on Junior while you were pedaling or painting away.

In Knoxville, Harnett converted one of the Movie King theater rooms into a virtual skydiving club, where he set up a few giant vertical wind tunnels that you’d jump into and get the illusion of skydiving as the blowing air suspended you, and your VR goggles would show you the scenery of an actual skydive. And if you joined the skydiving club and you scored well enough on the point system they’d established, there was an actual skydiving club hooked up to an actual skydiving operator; the club rode a bus from the Movie King every other Saturday morning to get on a perfectly good airplane they’d jump out of.

They were opening new Movie Kings so fast that it was hard to keep track of them. None of their stuff was overly expensive; these were middle-class places. The Movie Kings all had restaurants in them, but while a few were steakhouses or seafood places that were high-end, most of what was there was more along the lines of a Chili’s or an Olive Garden. And in Irving, Texas, there was a Chili’s, and in Roanoke, there was an Olive Garden.

Newsweek had a cover story hailing Movie King as an American leisure revolution. In it, there was a sizable interview with Harnett, and he took pains to note that from the very beginning of his career as an entrepreneur, going back to his Ballyard Sports days, it was always a question of providing people with a chance to meet and enjoy each other.

He was even open about some of the things Movie King was doing that people might have been nervous about.

“Look,” he said, “I won’t deny it: we’ve data-mined the heck out of the whole country. We’re looking at everything about you that we can. But understand this — everything that we’re putting into the psychographic profiles of our customers and potential customers is already out there. You’ve already freely given it to somebody who’s selling it to us. So what are we using it for? We’re trying to figure out how to show you a good time!”

“But isn’t that a little Big Brother?” asked the interviewer.

“Well, if I know that I have 464 families with kids who are Movie King Founders’ Club members within a 10-mile radius of our location in, let’s say, Mesa, Arizona,” he said, “and I send out a text notification that next Sunday afternoon we’re going to have a special showing of the original Ghostbusters at a bunch of our locations across the country, and give them a link to click on that will let them reserve space in the theater and book their tickets on the spot, and I already have a predictive matrix that tells me I can get half of them to bite on it based on the information we already have on our clientele, what does that do? It allows me to get Bill Murray to Zoom in after the show for a 30-minute Q-and-A with the folks in the theater.

“I wouldn’t do that unless I knew I had 10,000 people across the country booked; if I didn’t know that, paying Bill to do the Zoom would be a speculative thing. But since I know those 240 families and 750 people in Mesa were going to come, and I could add it up around the country to hit my number, this idea is obviously going to work, and I can do this kind of stuff, going the extra mile for my customers, at scale.”

In suburban Pittsburgh, the Movie King was attached to a big shopping mall, so Harnett essentially bought the roof of the mall and turned the whole thing into a giant rooftop dog park, with real grass, rolling hills, and a couple of little water ponds. You’d bring your dog and you could hang out in the clubhouse, or you could leave and they’d watch your dog for you, all day if you wanted. You’d tell them when you were coming back to pick Fido up, and they’d have him ready for you, freshly groomed, fed, and nicely worn out.

And yes, Thursdays were Singles’ Days at the dog park.

He had a list of every dog owner in the Pittsburgh area, and amid a ton of publicity and digital advertising, he did a targeted direct-mail campaign with brochures of the dog park, and by the time it opened, he had 13,000 Founders’ Club members in Pittsburgh already signed up. That covered the entire cost of building the thing.

Harnett was scientific like that. And people went wild over the Movie Kings. We ended up buying four regional theater chains over the course of the summer to add to his locations, and he snapped up several dozen abandoned Cineplex properties to rebuild as Movie Kings. They were beginning to redefine what an entertainment complex would be in the 21st century.

Asked about why his approach was so successful, Harnett said something the whole theater industry knew but didn’t want said.

“Look,” he told the Newsweek reporter, “the theaters got lazy. They said, ‘We’re movie houses.’ That’s nice, but once all the movies were available for streaming and everybody got a 50-inch TV, our living rooms are movie houses. What are you selling now? Comfy seats and fresh popcorn?

“You’ve got to do better than that to get people out of the house. Traffic, parking, the rude guy who keeps getting up and making that aisle seat you wanted so badly into a bad choice… There had better be a really good reason why people would brave the hassle of coming to your place. Well, it turns out it’s quite doable to develop those reasons. You just have to care about your customers and put in the effort to give them what they want. And all of this is done on the basis of giving Movie King customers a good time that they’ll want to share with their friends and families over and over again.”

Meanwhile, Nachman, Frank Taylor and Gardocki, and I all flew into Baton Rouge, as Grant’s campus was something of a central location, to plan the follow-on list of productions. We’d found a director for Frank’s Merle Haggard-Walton Goggins movie and greenlit it, but we decided to produce it under Sunshine Films, which was the new division of Sunshine Records.

Frank had spent the spring and summer signing up acts, and he’d brought in a crew of promoters, producers, tech people and marketing experts who came up with a mobile music platform you could Bluetooth into your car stereo or smart TV, and it gave you a number of choices of “channels,” which were really more like playlists. You’d listen, and you could swipe on your phone for every song you liked, and you’d download it for a dollar, and then the app would store it and make your own playlists for you.

Which wasn’t all that different from what was out there, but Frank was leveraging Sunshine’s classic catalog and getting his new acts to cover the old songs, and what you could get on the Sunshine Records app was great stuff nobody had heard. When My Morning Jacket and Greta Van Fleet started doing rock covers of Hank Senior songs, and those broke out on the internet, the buzz was immediate. And of course, there were concert recordings galore, because the Movie Kings had music clubs in them where they were streaming simulcasts of concerts, all part of Sunshine’s label.

And now we’d be doing film and TV projects on that label.

John Rich approached us with a script about the early days of stock car racing and the bootleggers going semi-legitimate as race car owners and drivers. He said he wanted to star in it. We jumped on that project. We also jumped on a biopic of Dolly Parton that Frank managed to get Lainey Wilson attached to, because that was an obvious move.

Nachman had gone out and bought the film rights to Brian Kilmeade’s book about Andrew Jackson and the Battle of New Orleans, and by the time we had our meeting in mid-August, he’d locked up Chris Pine to play Jackson. Belmarsh also lined up The Bambino, a TV series based on the life of Babe Ruth; it was going to be a Boardwalk Empire-meets-The Great Gatsby period piece that took the viewer through The Babe’s hard-playing life and larger-than-life brash personality.

And Grant was digging into that massive catalog of Surge Vision’s and bringing out gems that simply needed polishing.

He had an old script from the 1970s called Vaccine G, which was a conspiracy thriller about a rogue government agency seeking to change the country’s demographics and make the people more docile by giving them a vaccine for a new virus. The script was written for a two-hour movie; Grant got it rewritten as a TV series. Amazingly enough, gruff old George the film editor was the guy who took that project on with the stipulation that he’d get a producer credit as well as a writer credit. Which he did, and he did a great job on the script.

But he still wore Grant out with complaints, mostly about me.

Surge Vision also had a comedy sitting in its archive called The Basshole. It was an old-school romp full of sight gags and hilarious sexual innuendo about a bass fishing tournament in Mississippi that all the rednecks were pulling out the stops to win. It was a low-budget thing and the kind of movie that the woke would absolutely hate, but there was so much easy humor in it, and the good guy wins and gets the girl in the end, and Grant was determined to make it. There was no way I was telling him no.

We had a couple of sci-fi shows — one was an outer space thing, the other was about time travel. We had a mob movie about a kid who gets sucked into La Cosa Nostra and his mother gets him out by signing him up to join the Navy, where he becomes a decorated fighter pilot in Korea. We had a TV show about four sorority sisters from Chapel Hill who go off on different paths after college and run into all kinds of compelling life events; Santiago’s assistant, Mary McLaughlin, brought us that project and talked Nachman into letting her direct it.

Derrick Washington had a comedy about a grifter who managed to scam himself a DEI job running a company that was going broke, and through a bunch of hilariously unexpected and definitely not DEI-oriented moves, turned it into a thriving business again.

We ended up green-lighting no less than 30 projects, a lot of which we were going to use CASTR for. Grant managed to get the heirs of a bunch of actors who had passed away to give Surge Vision the rights to their likenesses, and so we were casting some of them in the CASTR productions.

For example, an AI Robert Mitchum plays the sheriff in Miracle at High Rock, which was a series about a little village in Kentucky where a strange orb kept showing up over a hill overlooking the town, and it was healing the sick when it arrived. Nobody knew what the orb was, and so the question would be whether this was a religious thing or a UFO thing.

The amount of content we were dreaming up and/or finding and/or getting bombarded with was amazing. Grant reported that he had people lining up to see him to pitch projects everybody knew would find an audience, but couldn’t survive the traditional Hollywood vetting. For us, though, it was nothing to crash them out using CASTR, let Harnett’s Movie King members serve as focus groups, and then decide whether to release them or re-shoot them as full-on film productions. Either way, we were set up to generate a massive flood of IP.

And in my spare time, I was working on my own screenplay, which was a not-very-complimentary biopic of Barry Omobba. I figured nobody would want to act in that, at least not yet, so I was dabbling with scenes in CASTR as I wrote it.

Damn thing blew me away. It made me feel like I actually knew what I was doing.

And when I got back from Baton Rouge, Pierce and the Tuxedo Club had another of our semi-annual Jupiter weekends. PJ insisted on throwing a big party for the club at the house and made herself a hell of a good hostess. She even joined us on Pierce’s boat the next day and didn’t complain when Dave Norwood got a little too drunk and started singing the Barnacle Bill song in front of everybody. That was funny as hell 20 years ago; not so much now. But then again, the fact that Dave is a state supreme court judge in Alabama did lend a little bit of comedic irony to the situation.

And Sharryn Kelly had me back on her show for a reprise of that initial interview, and she asked me what it was like to fix American culture.

“Well, it’s not fixed yet, Sharryn,” I said. “But we’re off to a pretty decent start.”

I’m not gonna lie. August was a hell of a good month.

![Gavin Newsom Threatens to 'Punch These Sons of B*thces in the Mouth' [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Gavin-Newsom-Threatens-to-Punch-These-Sons-of-Bthces-in-350x250.jpg)

![ICE Arrests Illegal Alien Influencer During Her Livestream in Los Angeles: ‘You Bet We Did’ [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/ICE-Arrests-Illegal-Alien-Influencer-During-Her-Livestream-in-Los-350x250.jpg)