“The spending plans I am setting out today are possible only because of the decisions I took in the autumn to raise taxes and the changes to our fiscal rules, every one of which was opposed by the parties opposite. Today, they can make an honest choice and oppose these spending plans as they opposed every penny I raised to fund them, or they can make the same choice as Liz Truss: spend more and borrow more, with no regard for the consequences.”

This is an interesting line from Rachel Reeves’ speech to the House of Commons yesterday. They imply that her latest spending spree (such as it is, see below) has been paid for by her earlier, promise-breaking tax rises – without, quite, saying it explicitly. Because that would be lying.

As almost every observer immediately noticed, the Chancellor has not actually set out how she’s going to pay for all this. Which means that either she’s going to break one of her fiscal rules (“day-to-day Government spending should be paid for through tax receipts”), or she’s going to raise taxes later this year. After having promised last time was the last time.

We shall then, presumably, be treated to an odd bit of dissonance. Yesterday, when justifying spending, Reeves’ line is that Labour’s economic management is paying dividends. Yet at that future date, when she needs to raise taxes, she will presumably need to return to the old line about the Conservatives having wrecked the nation’s finances.

It isn’t obvious how both of those narratives can be true, at least in that order, and making the announcements on different days won’t quite mask the conflict. Perhaps the Government will present the economy as a sort of sine wave, oscillating between fixed and broken as the moment requires. Or say that Mel Stride is sneaking into the Treasury and switching the economy off when no-one is looking.

But in fairness to Reeves, she certainly couldn’t have deployed them on the same day. The only coherent story that could fit both the spending and the attendant tax rises at the same time is the real one: that the Government, less than a year after a landslide election win, has run out of money and been spooked into making bribes, years ahead of a general election.

Anyway, let’s look at the actual spending review. Here is the document, for those reading along at home. It is, perhaps deliberately, slightly impenetrable at first glance.

The spending tables, for example, all sport two different numbers under the overall heading ‘Average annual real growth’: on the left is a number labelled ‘Phase 2 Period’, and on the right is a usually larger number labelled ‘SR25 Period’. There is no key explaining what these two things are.

A casual reader might, reasonably, infer that ‘SR25’ means ‘Spending Review 25’ (it does) and thus that column denotes what Reeves announced yesterday (it does not). In fact, yesterday’s announcements were ‘Phase 2’; the ‘SR25 Period’ helpfully extends backwards in time to cover spending the Chancellor already announced. Hence the (usually) bigger numbers.

The only other thing needed to decode the tables is to know that ‘Resource DEL’ refers, basically, to revenue expenditure (i.e. day-to-day spending, costs) and ‘Capital DEL’ refers to the capital budget, i.e. what can be properly termed investment. So armed, let’s look at some of them.

We’ll start with Health (Table 5.6). Labour’s website currently boasts of its plan to ‘Build an NHS fit for the future’, with a whole section on modernisation decrying the scarcity and age of its equipment. New equipment is a capital expense, and prior to yesterday Wes Streeting had only been given £6bn in extra capital funding. Surely yesterday’s record announcement fixed that?

The Capital DEL increase of the entire Department of Health and Social Care in Phase 2 is… 0.0%. Zero point zero per cent. Nothing, to a decimal place. Alas.

(Amusingly, even Reeves’ headline-grabbing revenue expenditure uplift only takes the average increase in NHS spending barely above the 2010-2024 Conservative average.)

Well, times are tough and not every department can be a priority. What about Justice? Labour has promised to deliver 20,000 prison places, and building prisons is capital investment, so… Ah. The Phase 2 increase in the MoJ’s capital budget is actually -2.1 per cent. One wonders how many new cells you can get for that.

Still, at least it’s only capital spending – the Treasury has never shown much of a liking for that. The poor Home Office has actually had its revenue budget cut (annualised Phase 2 real growth rate: -1.7%), which presumably isn’t going to make clearing the asylum backlog any easier.

All this is very bad, obviously, if you live in the country to which these numbers apply. But if you can detach yourself from that for a moment, it really is just an extraordinary spectacle – the fiscal equivalent Sideshow Bob walking into every rake he can find.

When Reeves first presented her ‘whole-parliament’ spending plans, they were in one respect a radical innovation. Normally, a government undertaking austerity front-loads the pain, so that the medicine has started to pay off, and generate some headroom for goodies, by the election.

The Chancellor, by contrast, announced a couple of good years early on, followed by a couple of very lean years indeed in the run-up to the next election, apparently in the hope that growth would just sort of happen once the Tories were no longer in charge. Yet despite her decision to crank up taxes on employers employing people, it has not.

After that, the story is just a tour of pieces we’ve already written: Reeves’ borrowing has increased the Government’s exposure to the bond markets; her big no-strings-attached bungs to the public sector unions has only encouraged them; lying to herself over Fuel Duty will punch a £4bn black hole in her numbers every year she does it; spending all the fiscal headroom afforded by the OBR’s forecasts means she has to make fresh cuts or tax hikes every time it adjusts them (as it will in October).

And below all that, the grinding reality of an ageing population. By 2028/9, ~16 per cent of British GDP (or ~35 per cent of all state spending) will be spent solely on pensioners and the NHS, up from ~13 per cent and ~30 per cent respectively in 2023/4. And those numbers are only going one way.

Fortunately, this far-sighted government has tasked Dame Louise Casey with coming up with plans for a national care service. If you’re wondering how that will fit into Reeves’ spending plans: the Treasury have punted the whole question out past the next election. It would hardly do if Labour had to introduce a Dementia Tax, would it.

In sum, then, yesterday’s Spending Review was basically a paradigmatic example of the doom spiral I described last September, wherein runaway revenue expenditures “are eating British politics from the inside out”. Faced with an ever-direr fiscal outlook and essential state functions teetering on the point of collapse, the Chancellor just cut the courts and prisons budget, and held NHS investment at zero, to hand three quarters of a billion pounds a year to pensioners who, not exclusively but overwhelmingly, don’t need it.

I wrote previous that if character is who you are in the dark, character in politics is who you are when the cash runs out. And when confronted with a choice between cutting the least-defensible welfare spending or letting the entire rest of the state fall to pieces, it turns out Labour aren’t that different from us.

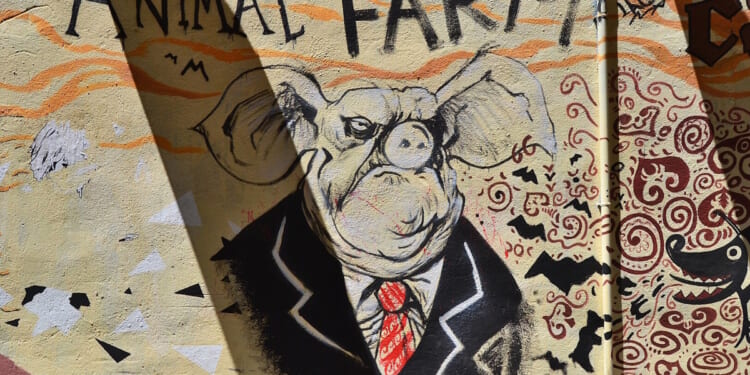

“The creatures outside looked from pig to man, and from man to pig, and from pig to man again: but already it was impossible to say which was which.”

![Former Bravo Star Charged After Violent Assault Using a Rock-Filled Sock in Tennessee Walmart [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Former-Bravo-Star-Charged-After-Violent-Assault-Using-a-Rock-Filled-350x250.jpg)

![Karoline Leavitt Levels CNN's Kaitlan Collins and Other Legacy Media Reporters [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Karoline-Leavitt-Levels-CNNs-Kaitlan-Collins-and-Other-Legacy-Media-350x250.jpg)

![Man Arrested After Screaming at Senators During Big Beautiful Bill Debate [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Man-Arrested-After-Screaming-at-Senators-During-Big-Beautiful-Bill-350x250.jpg)

![Illegal Alien Walked Free After Decapitating Woman, Abusing Corpse for Weeks [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/1753013138_Illegal-Alien-Walked-Free-After-Decapitating-Woman-Abusing-Corpse-for-350x250.jpg)