CNA Staff, Apr 25, 2025 /

09:00 am

A Texas-based bioengineering company sparked headlines across the world earlier this month when it announced it had done the seemingly impossible: brought a long-extinct species, the dire wolf, back from the dead.

Here’s what Catholics should know about the dire wolves and what the Church might have to say about “resurrecting” extinct species of animals.

A Colossal claim

Colossal Biosciences, a private company based in Dallas, announced April 7 the births of three genetically-modified puppies they say are not merely wolves but dire wolves — a species that roamed the Americas as a top predator for tens of thousands of years but which went extinct naturally around 12,500 years ago.

The company was cofounded by the famed Harvard geneticist George Church, who has been active in the field of species “de-extinction” for decades. (Its investors include George R. R. Martin, author of the “Game of Thrones” fantasy series; dire wolves feature prominently in those stories.)

To create the puppies, scientists extracted and sequenced ancient DNA from two dire wolf fossils, compared the ancient genomes to those of several living relatives including present-day wolves, and identified gene variants specific to dire wolves. They then edited a donor genome from a gray wolf and cloned those cells into gray wolf eggs before finally transferring the embryo into a surrogate wolf.

Colossal says the puppies were born in October 2024 and are currently “thriving” on a vast, secure ecological preserve in an undisclosed location. (Comparisons to “Jurassic Park” were swift and inevitable.)

Long term, Colossal says it plans to restore the species “in secure and expansive ecological preserves, potentially on Indigenous land.”

Scientists, journalists, and critics were quick to scrutinize Colossal’s claims that the creature they had created was truly a dire wolf — i.e. the first truly “de-extincted” species. National Geographic said the puppies are “better understood as slightly-modified gray wolves rather than true dire wolves.”

Nevertheless, some scientists have hailed the announcement as a major breakthrough and have expressed hope that the technology Colossal is perfecting could be used to help existing endangered species come back from the brink.

The Church’s response to gene editing

“Gene editing” is not in itself a new technology, and the Church has addressed its use several times in recent decades, noting that the practice holds promise for curing and preventing diseases, alleviating suffering, and promoting the common good, even among human beings.

Recent technological advances, such as CRISPR, have made gene editing simpler, cheaper, and more effective — but also has brought with it serious new ethical concerns.

In 2018, for example, a Chinese scientist announced the birth of CRISPR-modified babies whose genes had been edited while they were still embryos. The announcement was widely criticized in the scientific community as unethical and the scientist, He Jiankui, later faced punitive measures from the Chinese government for violating regulations surrounding gene editing.

From a Catholic perspective, the technology is addressed chiefly in the Church’s 2008 instruction Dignitatis Persone.

(Story continues below)

Subscribe to our daily newsletter

In a section on gene therapy, Dignitatis Persone notes that gene editing procedures used on somatic (body) cells “for strictly therapeutic purposes are in principle morally licit,” while at the same time firmly rejecting the editing of human “germ line” cells such as sperm and eggs, since such alterations could be heritable and harm the resulting babies. The instruction also warned against a “eugenic mentality” that aims to improve the human gene pool.

So the Church has said that the use of gene editing in humans can be beneficial within certain ethical parameters, but what about a Catholic view of its use in animals?

Taking a broad view, the Church teaches that mankind was granted dominion over the “mineral, vegetable, and animal resources of the universe” (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2456) but that this dominion is “not absolute” and comes with important moral obligations, particularly a view to “the quality of life of [one’s] neighbor, including generations to come,” as well as “a religious respect for the integrity of creation” (CCC, 2415).

Pope Francis in his expansive 2015 encyclical Laudato Si’ further addresses a Catholic view of ecology as it relates to the natural world. In his encyclical, Francis notes that humans are called to respect creation and its inherent laws, recognizing that God founded the earth “by wisdom” (Prv 3:19). Creatures are not to be “completely subordinated to the good of human beings, as if they have no worth in themselves” (Laudato Si’, 69).

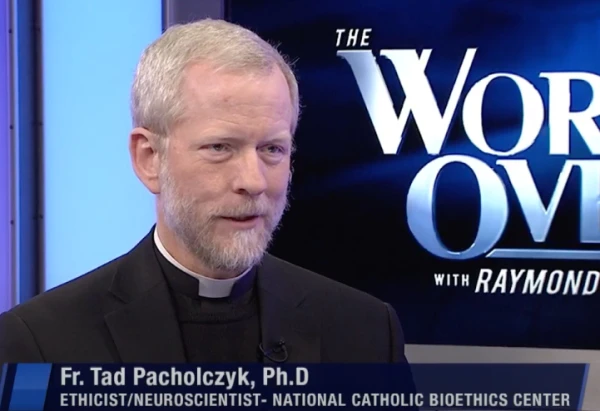

Father Tad Pacholczyk, a senior ethicist at the National Catholic Bioethics Center, commented to CNA that while Colossal’s claims are, from a biotechnology standpoint, very impressive, he has “lingering questions about the basic motivation behind the endeavor.”

“Biodiversity is a feature of the planet that has waxed and waned over eons. During the history of the earth we have had, by some estimates, 5 billion different species. The majority of these species have been wiped out by a range of forces, whether volcanic eruptions, habitat destruction, disease, asteroid impacts, etc. Why presume we have a duty to bring any of them back?” Pacholczyk said in emailed comments to CNA.

Other scientists have pointed out that breeding an animal with many of the same traits as an extinct animal — in the dire wolf’s case, chiefly a white coat and large size — is not the same as “bringing back” a long-gone species. Scientists could breed elephants with hairy brown coats, for example, but those would still be elephants, not wooly mammoths.

“To bring back the real dire wolf would require synthesizing and manipulating billions of DNA base pairs and arranging them into chromosomes, which current technology is unable to do,” Pacholczyk said.

Moreover, Pacholczyk opined that Colossal’s decisions to focus their efforts heavily on animals with broad cultural appeal, such as dire wolves and wooly mammoths, may be driven by the need to attract investors, because “the expenses involved in de-extinction efforts are staggering.”

“Ethically speaking, one wonders if such enormous expenditures can really be justified, when far lower financial commitments could safeguard habitats and bio-niches of currently threatened species,” Pacholczyk said.

(Back) home on the range

OK, so what about Colossal’s plans to someday reintroduce the wolves into the natural environment? After all, there have been success stories when it comes to human-led reintroduction of species previously dislodged from an ecosystem — including, perhaps most famously, the reintroduction of gray wolves in Yellowstone National Park in 1995.

Practically speaking, if Colossal’s reintegration does happen, the dire wolves will find themselves in an ecosystem that is dramatically different from the one in which they previously lived — not least because of the fact that almost the entirety of human society has arisen in the time since it went extinct. Also, as the New York Times notes, they would encounter an environment where they would potentially have to compete with existing gray wolves.

The upshot is that despite many advances in recent years, scientists’ grasp of the “intricacies of ecosystems on the planet is quite limited, because these systems involve a plethora of complex variables, and to suppose we can really forecast which ecosystems would benefit from the reintroduction of certain de-extincted animals is highly doubtful,” Pacholczyk said.

“There also remains the perennially important ‘law of unintended consequences,’ where we could end up reintroducing a de-extincted species only to be caught off guard when it suddenly expanded out of control, ravaged specific habitats and wiped out other species.”

Echoing Pacholczyk, Laura Altfeld, an associate professor of biology and ecology and chair of the Department of Natural Sciences at St. Leo University, a Catholic college in Florida, told CNA in written comments that there could be potential downsides to reintroducing extinct species to existing ecosystems, both for the introduced animals and for the rest of the ecosystem.

This is because, in part, most ecosystems as they exist today are highly modified and degraded as a result of human activities, which could pose challenges for reintroduced species if they lack the necessary adaptations that modern species have developed to deal with a world dominated by humans.

If done right, however, there is potential that reintroduced species could aid in “restoring ecosystem functions and boosting biodiversity in some of our ecosystems,” Altfeld continued, especially in high latitudes, such as the Arctic, where climate change continues to rapidly alter ecological conditions.

Whatever happens next in terms of a potential reintroduction, a program as ambitious as Colossal’s should be driven by “ecological expert consensus” and not commercialism, she cautioned.

“This technology is incredibly powerful and should absolutely be used with caution, and with serious forethought into animal welfare considerations and clear connection to purpose (conservation, for example).”

Altfeld did go on to add, however, that Colossal’s technology could be helpful as a means of saving existing species at risk of or on the verge of extinction.

Among some endangered species which have very small remaining populations, a lack of genetic diversity caused by inbreeding can be a big problem. Scientists are already using a technique called genetic rescue, which involves introducing genetic material from a similar species, through outbreeding, in order to try and save an endangered one.

“There are endangered animal species whose wild and captive populations are so significantly genetically bottlenecked that they will most certainly go extinct without intervention. Any technology that can be used to reintroduce genetic diversity has the potential to be of extreme benefit,” she wrote.

The potential use of Colossal’s technological advances to aid in the genetic diversity of endangered populations “is the most valuable, in my opinion. And the fact that they are willing to work with conservation researchers globally to aid in species conservation is impressive,” Altfeld said.

Altfeld said she plans to continue to engage her zoology students in conversations about the ethics of gene editing, with the dire wolf announcement just the latest in a continuing line of “rapid advancement” in the field that she expects will continue.

“Our students will be moving into careers that may directly engage with the technologies that are being developed by Colossal, so engaging them in conversations about the ethical and scientific issues surrounding genetic engineering are essential for us as educators,” she concluded.

“I encourage everyone to do the same, whether they are Catholic or not. There is never a downside to becoming knowledgeable and conversant with one another, even about the most challenging and controversial of topics.”