Lord Hannan of Kingsclere was a Conservative MEP from 1999 to 2020 and is now President of the Institute for Free Trade.

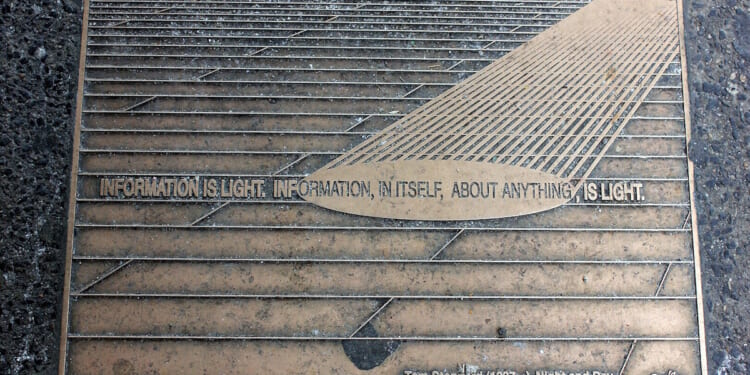

I remember stumbling out of the National Theatre at the age of 21, speechless as my friends Mark, Giles and Sara animatedly discussed Arcadia, the wonder we had just witnessed. I thought then, and I have thought ever since, that Tom Stoppard was the greatest English playwright since… well, since the man he playfully called the Champ.

That might seem an extreme view, but it is surprisingly widely held. Last week saw our entire literary establishment, plus Sir Mick Jagger and the King, lining up to salute Sir Tom as the most accomplished stage writer of our age.

Stoppard won every prize going: five Tony Awards, three Oliviers, an Oscar and a Golden Globe, a knighthood and an Order of Merit. Yet even he, the grandest of the grand old men of letters, could not come out and admit that he was a Tory.

Any ConHome reader familiar with his oeuvre will have sensed that he was One Of Us. We know how to spot the tells. His tone was detached, wry, ironic, respectful of tradition, sceptical of utopianism. His most foolish characters were those ruled by the revolutionary certainties that were de rigueur among intellectuals while he was writing.

Very occasionally, Stoppard let the politics shine through. Every Good Boy Deserves Favour (1977) and Dogg’s Hamlet, Cahoot’s Macbeth (1979) were overt attacks on Soviet totalitarianism – though both were also so much more that it feels slightly cheap to label them.

More usually, though, what we saw were not blinding conservative principles but the gentle glow of a conservative temperament. The Invention of Love (1997) is infused with Scrutonian melancholy, a yearning for the lost classicism of the Victorian age. Travesties (1974), based on the coincidence that Lenin, James Joyce, and the Dadaist writer Tristan Tzara were all in Zürich in 1917, portrays both revolutionary writers and actual revolutionaries as delusional, chaotic and comical. Jumpers (1972) and Rock ’n’ Roll (2006) pulse with distaste for intellectuals who embrace rigid ideologies. Arcadia (1993) is rooted in reverence for order and tradition – as much in its form as in its content.

Stoppard’s final play, Leopoldstadt (2020), was elegiac, shot through with an awareness of the precariousness of our civilizational inheritance. Appropriately, it was the last play I watched before the cataclysm of lockdown, and I couldn’t help noticing that the foyer was pullulating with Tories.

(“This is just another of those bird ’flu/swine ’flu/Ebola type scares, isn’t it?” I asked the great Matt Ridley, whom I bumped into during the interval. “I’m not sure” replied the Rational Optimist gravely. “A virus with long incubation and high virulence could be seriously bad news”.)

Stoppard’s conservatism is largely in his subtext. With the exception of his attacks on censorship in his native Czechoslovakia, none of Sir Tom’s plays was political. They were too multi-faceted for that.

Some 15 years after its first run, I watched a new production of Arcadia in the West End with the same friends. “Can you all remember what it’s about?” I asked as we took our seats. “Maths,” said Mark. “Byron,” said Giles. “Gardens,” said Sara (whom I had married in the mean time).

My point is not that Stoppard was a passionate Tory. He wasn’t. When, as a young man, he interviewed for a job on the Evening Standard, the editor, Charles Wintour, found his answers suspiciously vague. “Can you tell me the name of the current Home Secretary?” he asked. “Look, I said I was interested in politics, not obsessed.”

Stoppard wore his opinions lightly, never allowing them to distort his art – a rarer approach, in the late Twentieth Century, than it should have been. Asked what his breakthrough play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (1966) was about, he replied gaily, “It’s about to make me very rich”.

In fact, the play is a was an ingenious meditation on fate and predestination. The spread of sim games in the late 1990s led to an explosion of movies based on the idea that artificial creations might develop self-awareness: The Thirteenth Floor, The Truman Show, The Matrix, Never Let Me Go and many more. But none came close to the power of R&G thirty years earlier.

Would Stoppard have been a better writer had he felt able to express in public his private admiration for Margaret Thatcher? Had he strayed beyond the relatively acceptable issue of opposition to Soviet censorship to make his plays political?

Emphatically not. Conservatism, as Roger Scruton liked to say, is an instinct, not an ideology. A proper conservative does not take politics too seriously. Ken Tynan, who was anything but a Tory, put it well:

“For Stoppard, art is a game within a game, the larger game being life itself, an absurd mosaic of incidents and accidents in which (as Beckett, whom he venerates, says in the aptly titled Endgame) ‘something is taking its course’.”

Quite. Ever Tory, on some level, recognises that sentiment. The artistic establishment might not have forgiven Stoppard had he made it explicit. But we who do, we surely should recognise and mourn the passing of one of our own.