I received a copy of Heterodoxy in 1992 from a relative who picked it up at one of the two main Harvard Square newsstands. If it wasn’t the first conservative periodical that I had read, then it was probably the first one that I had read outside of a library in my own home. Simultaneously funny and serious, its low-budget format gave it, intentionally or unintentionally, a fitting samizdat quality. Under the regime of political correctness — what we called woke back then — Heterodoxy acted, if for a period during its brief but glorious 1990s lifespan, as the dissident publication.

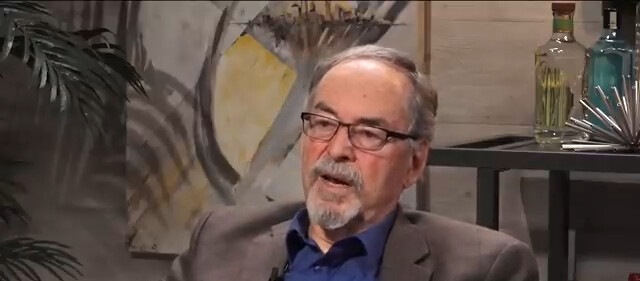

David Horowitz, the man behind that publication, died this week at 86. That number, rather than his death, stands out as the shocking aspect of that sentence. A strange combination of California Cool and New York Jew, Horowitz identified, as his goatee, longish hair, and fiery energy indicated, as someone at least a decade younger than his actual age. This perhaps explains why, from his days as Ramparts editor in the 1960s through his efforts to rebut the drive for reparations in the early 2000s, Horowitz connected with the young.

When he was younger, before woke or political correctness, he was a Communist — and one brought to that extreme place on the ideological spectrum not through persuasion but birth. His parents, New York City school teachers, were members of the Communist Party. This imbued in the Stalinist son a sense of membership in the elect, the enlightened, the anointed. “I was 10 years old, but I thought of myself as someone who could lecture the President of the United States on the difference between right and wrong, and thus change the course of history,” the red-diaper baby wrote in his landmark autobiography, Radical Son. “I was just starting out in life, yet I was already suspended so high above everyone else, was there anything I could do but fall?”

As for Frank Meyer, the subject of my forthcoming book The Man Who Invented Conservatism: The Unlikely Life of Frank S. Meyer, a friend’s death, for which in an indirect way he felt responsibility, catalyzed Horowitz’s shift from left to right. Horowitz recruited Betty Van Patter to act as an accountant of sorts for various Black Panther efforts in Oakland in the mid-1970s. She saw numbers that did not add up. Then the cops pulled her murdered corpse from San Francisco Bay.

“In pursuit of answers to the mystery of Betty’s death,” he wrote in Salon about a quarter-century ago. “I subsequently discovered that the Panthers had killed more than a dozen people in the course of conducting extortion, prostitution and drug rackets in the Oakland ghetto.”

The epiphany came. He had served not just a lie but an evil so profound as to command lies to protect the cause from consequence for any of its crimes, including murder. Horowitz changed his mind. His former comrades never forgave him for this egregious sin. He spearheaded something amorphously known as the “second thoughts” movement. Christopher Hitchens reacted especially viciously to Horowitz’s turn. Within a decade or so, Hitchens himself experienced some second thoughts, which seemed a tacit admission of the correctness of what he had condemned in such a catty manner in Horowitz.

About a year after I first read Heterodoxy, I saw David Horowitz deliver a Lenin-esque stemwinder, in style but not substance, at the Sheraton Commander a few blocks from the Out of Town News or Nini’s Corner or wherever my issue of Heterodoxy was purchased. I saw him speak the next year at a freedom of speech conference at Columbia. A few years later, I got to know him as I organized several conferences in which he spoke, to include ones at UCLA, the University of Pennsylvania, and the University of Chicago, which allowed us the opportunity to appear on Milt Rosenberg’s Extension 720 together with a student (and miss William F. Buckley’s delivery of the keynote of my conference). Horowitz was either incredible or horrible as a speaker at these conferences, with little in between.

His books followed this pattern. The histories he wrote with Peter Collier, particularly The Kennedys, were page-turners. His Radical Son did big business. It is one of many books compared to Whittaker Chambers’s Witness — and one of the few in which the comparison does not strike as hyperbole. Later, he cranked out title after title. Some felt sloppy and thrown together. They were, like David, uneven.

Unlike David, I grasped that I was not made for the conflict business, so, after more than a decade of working professionally to reform the campuses, I left that line of work. Our paths nevertheless continued to cross. After our campus collaborations, I came to David as a writer. He and his longtime loyal lieutenant, Jamie Glazov, generously opened up FrontPageMag to my articles. It helped me stay afloat during my freelance years. That publication remains among the man’s many legacies.

At his death from cancer, as reparations bills accelerate through California’s state house, campus antisemitism and reflexive anti-Israel animus grow, and DEI shapeshifts as a means of carrying on the struggle under a less tarnished brand, it strikes that America needs David Horowitz now more than ever. Rest in peace.

READ MORE from Daniel J. Flynn:

Trump’s De Facto Election Interference Ensured the Left’s Victory in Canada

Trump’s Strong-Arm Tactics Convince Mexico to Take Action Against Cartels

![Pentagon Begins Booting Trans Troops After Supreme Court Greenlights Ban [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Pentagon-Begins-Booting-Trans-Troops-After-Supreme-Court-Greenlights-Ban-350x250.jpg)

![Trump Posts Hilarious Pope Meme, Leftists Immediately Melt Down [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Trump-Posts-Hilarious-Pope-Meme-Leftists-Immediately-Melt-Down-WATCH-350x250.jpg)

![Soros Network, Others Behind LA Riots [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Soros-Network-Others-Behind-LA-Riots-WATCH-350x250.jpg)