Helen Edward recently stood as Parliamentary Candidate for Kingston and Surbiton. She is also Deputy Chair for CWO London and CPF London Ambassador.

As unemployment hits a record 5 year high of 5.1 per cent this week, a recent session of the Modernising Employment All-Party Parliamentary Group on Timeless Skills: Embracing Age Diversity at Work, one message came through clearly: the UK does not have a willingness-to-work problem. It has an incentives problem.

Older workers want to return or rebalance their working lives. Young people want a first rung on the ladder. Employers want to grow. Yet too many hiring decisions are being quietly delayed or abandoned altogether.

The reason lies not in attitudes, but in how we price and regulate employment at the margin – especially in a weakening economy.

The APPG heard from employers, academics and practitioners that age-diverse teams perform better. Skills such as judgement, resilience, emotional intelligence and strategic thinking improve with age. Over-50s already make up roughly a third of the workforce, and many want to continue working – but not necessarily in the same roles or patterns.

Yet recruitment systems are not designed for multi-stage careers. CV-based hiring correlates poorly with performance. Algorithmic screening embeds bias. Job adverts often deter older applicants unintentionally. Flexibility and health-aware job design are too often absent.

At the other end of the labour market, nearly one million young people are not in education, employment or training. Entry-level jobs are disappearing, and with them the first rung of opportunity.

What links these two groups is not age, but proximity to the marginal hiring decision.

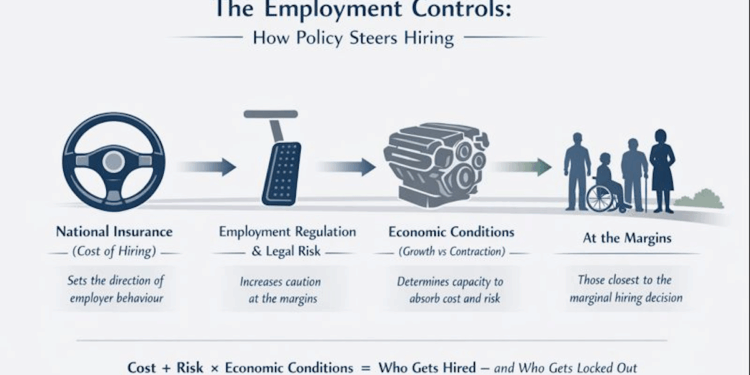

Employer National Insurance is, in practice, a tax on employment. When it rises, the cost of taking on, or keeping on, a worker rises with it.

In a growing economy, businesses may absorb that cost or delay its impact. In a contracting or fragile market, they do something much simpler: they hire less.

Crucially, employers do not respond evenly across their workforce. They respond at the margin. And the marginal hire is typically:

- a young person without experience, or

- an older worker returning after a break or career transition.

When the cost of employment rises, risk aversion follows. Entry-level roles are frozen. Returnships are postponed. Flexibility disappears. Inactivity rises – not because people will not work, but because the system discourages employers from offering work.

National Insurance is not the only lever in the system – but it is a steering wheel. And at present, it is steering away from inclusion.

Context is everything. In buoyant labour markets, inefficiencies are masked. In weaker ones, they are exposed.

With growth slowing and margins tightening, employers become more cautious. Any increase in the cost or complexity of hiring has a disproportionate effect on those furthest from the centre of the labour market.

Older workers take longer to find work. Younger workers struggle to find it at all. Both outcomes increase inactivity, reduce growth and place greater pressure on the state.

The APPG heard estimates that age-related exclusion alone costs the UK economy tens of billions of pounds each year. This is not merely a social issue; it is a structural growth failure.

Cost is only half the equation. Risk is the other.

As the Employment Rights Bill progresses through Parliament, employers are also factoring in changes to dismissal rules, flexibility, contractual arrangements and compliance burdens.

Individually, many measures may be well-intentioned. Taken together – and layered on top of a rising tax burden on employment following two Budgets in one year – they alter behaviour.

When both the price of hiring (National Insurance) and the perceived risk of hiring rise at the same time, the rational response in a weak market is caution. The damage does not show up as mass redundancies, but as jobs that are never created.

If National Insurance is a steering wheel, it can be turned deliberately – but only if policy design targets behaviour, not just cost.

Blunt exemptions risk deadweight. Smarter options might include:

- time-limited NI relief for net new hires

- relief linked to structured returnships, retraining or flexible job design

- raising the secondary threshold to reduce the burden on lower-paid, entry-level roles

Used carefully, NI can encourage job creation, second chances and smoother transitions across longer working lives.

The APPG made one thing clear: people are not the problem. Systems are.

Older workers are not less capable. Young people are not less motivated. Employers are not hostile to diversity. But incentives matter – and when they are misaligned, outcomes follow.

If we want more people working at every age, we must stop pricing and over-risking the marginal job out of existence.

National Insurance alone will not solve this. Recruitment practices must modernise. Flexibility must become normal. Skills and pension pathways must support longer, more varied careers.

But if we get the steering wrong, none of the rest will matter.

![Florida Officer Shot Twice in the Face During Service Call; Suspect Killed [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Inmate-Escapes-Atlanta-Hospital-After-Suicide-Attempt-Steals-SUV-Handgun-350x250.jpg)

![Keith Ellison Caught Promising to Fight State Agencies for Somali Fraudsters [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Keith-Ellison-Caught-Promising-to-Fight-State-Agencies-for-Somali-350x250.jpg)