James Crouch is head of policy and public affairs research at Opinium.

For Kemi Badenoch and her Conservative colleagues, the rise of Reform UK poses a series of acute policy challenges, raising the question of what strategy should the party take.

The question is not simply how to neutralise Nigel Farage’s insurgent party, but where Conservatives can differentiate themselves, ensuring clear political “blue water” between the two.

The evidence suggests that while Reform’s appeal on immigration and law and order issues is undeniable, the Conservatives’ best chance of building a winning platform lies in reclaiming the economic argument.

Reform’s strengths on immigration and crime

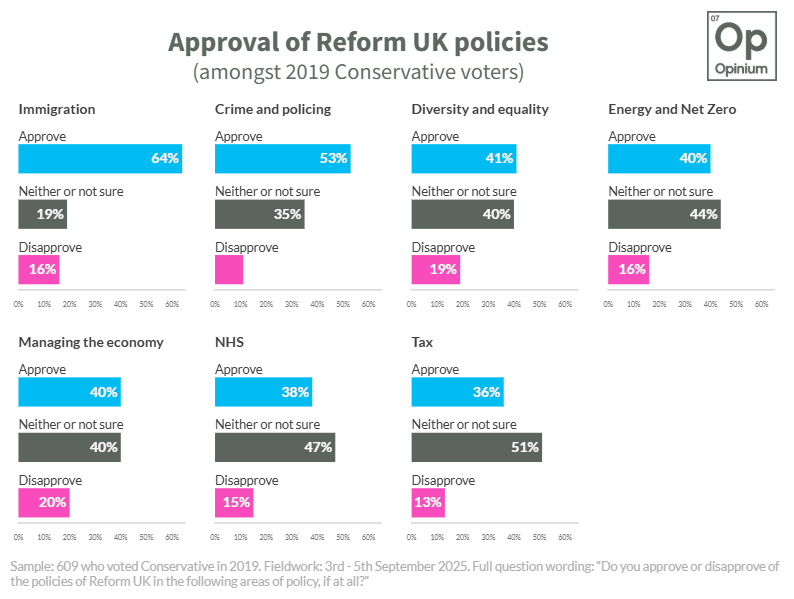

It is hardly a surprise that Reform’s stance on immigration resonates deeply with 2019 Conservative voters. Among this cohort, the Boris Johnson coalition that secured a 45 per cent share of the vote, net approval of Reform’s approach to immigration sits at +48, with 64 per cent approving and only 16 per cent disapproving. With such a threat on the right, Conservatives are is right to think that they cannot afford to duck the immigration issue.

Similarly, Reform enjoys strong backing on crime and policing, with a net approval score of +42 (53 per cent approve, 11 per cent disapprove). These are not marginal issues: they go to the heart of the public’s trust in government to maintain order and fairness. That makes it imperative for Conservatives to demonstrate they are serious about tackling rule breaking, from low-level antisocial behaviour to organised crime.

Robert Jenrick’s focus on everyday law-breaking, such as fare-dodging on the London Underground, is well judged.

Likewise, Chris Philp’s criticism of Labour’s decision to scrap the Rwanda deportation scheme days before it was due to begin reflects a public mood that has shifted in favour of the policy.

Polling shows 47 per cent now support reviving the plan, while just 25 per cent oppose it. These examples illustrate that Conservatives can respond credibly to Reform’s challenges. But doing so merely keeps the party in contention; it will not, by itself, win back disillusioned voters on ground where Reform will continue to present itself as a strong alternative.

Where Reform is vulnerable

The Conservatives’ real opportunity lies in areas where Reform is weaker, namely, economic credibility and taxation.

When asked about Reform’s approach to managing the economy, Conservative-minded voters gave Nigel Farage’s party its lowest score among the seven policy areas tested: a net approval of just +19 (40 per cent approve, 20 per cent disapprove). This is striking when set against the overwhelming backing for Reform on immigration and crime. It suggests voters remain unconvinced that Reform has the seriousness or competence to take major economic decisions. Indeed, when asked whether Reform “can be trusted to take big decisions,” respondents gave a net agreement score of only +13, with 43 per cent agreeing but 30 per cent saying they can’t be.

This is fertile ground for the Conservatives.

If they can present themselves as the party of economic stability and competence – especially against a Labour government vulnerable to accusations of economic mismanagement – they could exploit Reform’s relative weakness. Positioning the economy at the centre of their message would also allow the Conservatives to appeal not only to right-leaning voters but also to swing voters facing continuing economic pressure.

Tax is another area of opportunity. Reform records only a modest net approval of +23 (36 per cent approve, 13 per cent disapprove), with a striking 51 per cent of 2019 Conservative voters either unsure or having no opinion at all. That uncertainty represents political space. By offering clarity, especially an alternative approach to recent unpopular tax rises, the Conservatives can both differentiate themselves from Labour and present a more credible fiscal plan than Reform currently offers.

A strategic path forward

The data clearly shows that the Conservatives cannot retreat from the political battleground of immigration and crime. These are defining issues for many voters and wholly conceding them to Reform would be incredibly dangerous. However, to win back those tempted by Reform, Conservatives must do more than simply match the party’s rhetoric. They need to offer a convincing story about economic competence, tax fairness, and long-term prosperity.

The challenge, then, is one of emphasis. If Conservatives lead with an economic message, demonstrating competence, steadiness, and a commitment to easing the burden on households, they will exploit Reform’s vulnerability and occupy a more promising electoral ‘white space’. From that foundation, they can then more credibly assert their positions on immigration and other social issues. The order of priorities matters: without the economic platform, voters may still admire Conservative policies on crime or immigration but doubt the party’s capacity to govern effectively.

Labour’s policy choices may actually help here. By leaving space on taxation and risking its reputation on economic management, the government is writing the script for a Conservative fightback. The question is whether the Conservatives can unify around that script, articulate it with discipline, and convince voters that they – not Reform, and not Labour – offer the most credible path forward.

Reform’s rise represents a formidable challenge, but not an insurmountable one. Its appeal on core Conservative political territory is undeniable, yet it does have weaknesses. If the Conservatives want to win back a larger share of right-of-centre voters, they should lead with the economy.

Immigration and law and order policies may win attention; only a full-bodied economic vision will win back trust.

![Gavin Newsom Threatens to 'Punch These Sons of B*thces in the Mouth' [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Gavin-Newsom-Threatens-to-Punch-These-Sons-of-Bthces-in-350x250.jpg)

![ICE Arrests Illegal Alien Influencer During Her Livestream in Los Angeles: ‘You Bet We Did’ [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/ICE-Arrests-Illegal-Alien-Influencer-During-Her-Livestream-in-Los-350x250.jpg)