Mark Brolin is a political analyst, economist, and author. His most recent book is titled Healing Broken Democracies.

I’ll admit it: I was wrong. Back in November, when writing for ConservativeHome, I argued that Kemi Badenoch embodied the future of politics. She spoke with the urgency of a real reformer, brimming with impatience for outdated orthodoxies; a promising sign in a political landscape starved for fresh energy and genuine change. Yet, as events have unfolded, it has become clear that Badenoch excelled at saying the right things during the leadership contest, but has struggled to reform a party that may, in truth, be beyond reform.

It would be easy to lay the blame for the lack of a new direction solely at Badenoch’s feet. But doing so would miss the deeper issue: it now appears obvious that the real problem is the Conservative Party itself. Or, more precisely, the corporatist establishment faction that is out of step with general voter sentiment but still sufficiently in command, internally, to hinder real change.

For years, this faction has behaved much similar to all those centre-right parties across Europe which have appeared to take power for granted; echo chambers in which oligopolists, technocrats, international lobbyists and other Davos regulars provide each other with professional security and psychological reassurance. They proudly call themselves “moderates” or “grown-ups”, yet they have – together with traditional centre-left parties – been the architects of the radical shifts that underpin the so-called populist backlash: mass migration, cultural atomisation, centralisation of power and a curious tendency to apologise for the Western world even as others flock to join it. The have found ways to push their agenda forward, often sneakily, even when blatantly against the will of the people they claim to democratically serve.

My own error was underestimating the strength of the echochamber groupthink. Given how voters have repeatedly shouted “less establishment groupthink”, starting with the Brexit vote, the penny must by now surely have dropped, so I thought – that to connect more broadly it is necessary to appeal more broadly. If not before, then surely after the Labour general election landslide, right?

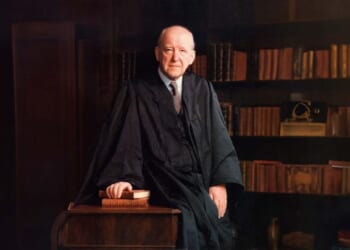

Wrong. Instead, the establishment faction figureheads – like John Major, Kenneth Clarke, David Cameron, George Osborne, Theresa May, Rishi Sunak, James Cleverly – have kept projecting the reasons for the turmoil created by themselves on everyone but themselves.

So still, to this day, arguing they were right all along, and that the “uninformed throwbacks” claiming otherwise – including the “opportunistic Reform splinter group” – will implode when reality hits. It seems like the movers and shakers within this faction have yet to take on board they are the ones already imploding following a reality hit. The fact that just about everyone else sees this quite clearly does not appear to matter.

Given the failure of the establishment faction to respect voter sentiment it is not hard to see how the talk about a “Davos conspiracy” has evolved. I am still convinced the more straightforward – and more plausible – explanation is that institutional capture (institutionalised groupthink) is remarkably resilient, even in the face of absurdity. Part and parcel of every institutionalised power cocktail is (unrecognised) self-interest and an escape route.

When pressure mounts, vague mutual finger pointing means no one is ever made responsible. Thereafter minimalist reform that, as far as possible, preserves the status quo: a tweak here, a new committee there. Sweeping change is deftly sidestepped by saying ‘not possible’ since power has been (again sneakily) handed to the – surprise, surprise – Davos minded courts. ‘Sorry, we tried.’ Leaving a system truly working to the advantage of insiders, including when keeping out outsiders.

Yet there has never been a grand master plan; even those at the top of the power pyramid did not intend for things to unravel as they have. Least of all within the Conservative Party. It all began, rather innocently, with major lobby groups advocating for cheaper labour and, by extension, higher net migration. From a CEO’s perspective, seeking to keep costs down is simply part of the job description. In earlier times, trade unions would have pushed back, and a fair compromise might have been reached to balance the needs of companies and local workers. Yet, one of the least discussed shifts in recent decades is that unions, too, have warmed to increased migration, if only to slow their own membership decline. So it followed that both sides of the labour market generously supported politicians and other commentators who consistently have been singing from the same corporatist hymn sheet.

The result? Years of quietly loosened border policies and a rulebook that’s been rewritten also in a countless number of other areas. Always, somehow, to the benefit of those closest to the levers of power. It is no wonder there is yet again a faint whiff of royal privilege in the air, with today’s (old industry) corporate giants often resembling semi-bureaucratic unaccountable behemoths.

All that’s missing, really, is the powdered wigs that make the courtiers almost indistinguishable. It is also no coincidence that almost all the real action and innovation is taking place in the tech industry, since still too new to be strangled by regulation. Nobody should be surprised that where the corporatist movers and shakers still rule supreme, such as within the EU apparatus, also tech sector regulations are coming thick and fast.

None of the architects of today’s stale set up have offered either traditional conservatism or market orientation in any real sense. They have offered one-eyed technocratic centrism dressed up in blue, and it really is indistinguishable from the equally one-eyed – yet unwaveringly smug – corporatist consensus that dominates Brussels, Berlin and Paris.

When a supposedly reform-minded figure like Badenoch must fight hard against the people of institutional sclerosis, even against today’s backdrop, does she really stand a chance? All previous reformers have been chewed up and spat out. Followed by all the usual suspects immediately arguing that since reform did not work, yet more de facto corporatism must be the way forward. So here we now are with a party in which any flicker of urgency is dulled by a culture in which far too many act as if they are taking their coffee with morphine.

The good news? The UK does not need the Conservative Party per se. If the party stops properly serving society voters will reward a party – new or old – doing better. That’s why recent gestures from The Spectator and The Telegraph, opening the door to alternative voices and shifting the debate, deserve credit. It is simply not enough anymore to shuffle the deck chairs or adjust the tone. Having said all this the way forward is also not to return the keys to the Conservative kingdom exclusively to the people’s wing. That would just continue the destructive ping pong game between rival factions. Truly grown-up and clearly defended bridge-building – precisely what Kemi Badenoch claimed to offer during the leadership election – is instead what has won elections since Benjamin Disraeli and onwards.

If Kemi Badenoch is not the real problem, but faces a brick wall when trying real change internally, she does not have to wait until she is ditched to cross over to another party. No leader, however compelling, can save a party that refuses to be saved.

![ICE Facility Under Siege in Portland as Mob Tries to Breach Cells [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/ICE-Facility-Under-Siege-in-Portland-as-Mob-Tries-to-350x250.jpg)

![MSNBC’s Nicole Wallace Cries Over Deported Illegal Alien Gang Members [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/MSNBCs-Nicole-Wallace-Cries-Over-Deported-Illegal-Alien-Gang-Members-350x250.jpg)