A controversial Republican president imposes stiff tariffs on America’s trading partners, seeks to expand America’s footprint abroad, keeps out immigrants he’s deemed “criminals” and makes it easier to fire government employees.

And he was swept into office amid voter frustration with the economy under his Democratic predecessor.

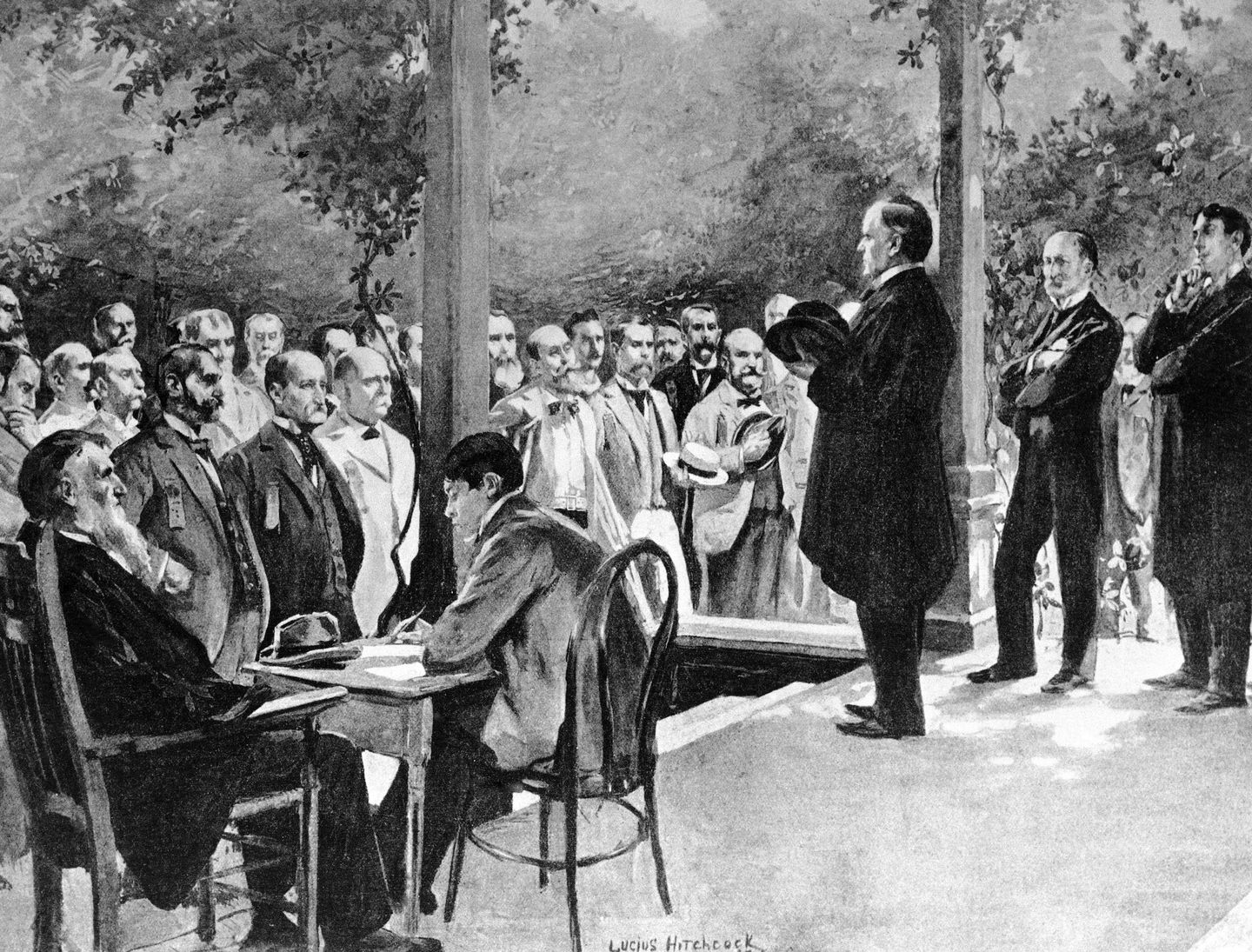

The year is not 2025 and the president is not Donald Trump. It’s President William McKinley, who was elected in 1896 and has become the model for Mr. Trump’s second term.

Mr. Trump isn’t shy about being a super fan of the largely forgotten 25th president, giving McKinley a moment he hasn’t had since he was assassinated 124 years ago.

At the American Business Forum last month, Mr. Trump praised McKinley as “a great president” before launching into an impromptu history lesson. He complained that President Theodore Roosevelt gets too much credit for McKinley’s policies and hailed McKinley’s time as governor of Ohio.

“He did a great job. Made the country very rich,” Mr. Trump said.

One of Mr. Trump’s first acts in office was to restore the name Mount McKinley to the highest peak in North America, rescinding President Obama’s order designating it “Mount Denali” to honor its ancient name.

“Presidents often latch on to previous presidents to justify their policies,” said historian Craig Shirley. “I think Trump finds McKinley interesting because he was part of the realignment of the Republican Party that made it more dominant in the industrial states. That’s where Trump gets his inspiration from.”

Mr. Shirley said McKinley is an unusual choice for Mr. Trump, the current torchbearer for the party of Ronald Reagan and Abraham Lincoln. He noted that like Mr. Trump, President Reagan wanted to reduce the size of government and return certain policies such as education to the states.

Mr. Shirley also said there were similarities between Mr. Trump and President Andrew Jackson, a populist who ran as a political outsider.

Regardless, there is no shortage of parallels between Mr. Trump and McKinley.

Perhaps the most obvious, and one cited most by Mr. Trump, is their mutual love of tariffs. While Mr. Trump insists “tariff” is the third greatest word in the English language behind “God and family,” McKinley referred to himself as a “tariff man standing on a tariff platform.”

Both men repeatedly said that high tariffs would restore American prosperity and protect workers. While in office, McKinley raised tariff rates on woolens, linens, silks, china and sugar. He also imposed a 12-year tariff that started at 52% in the first year — the highest in U.S. history — and averaged around 47% during its lifespan.

McKinley’s tariffs brought in $145 million, which would be roughly $5 billion today.

Mr. Trump’s tariff policy is still in flux as he strikes trade deals with other nations. Under Mr. Trump, however, the average effective tariff rate in the U.S. reached 17.9%, its highest total since 1934.

Toward the end of his presidency, McKinley began to soften on tariffs. He gave a famous speech in September 1901, making the case for more free trade and lowering tariffs, but the next day, an anarchist shot him, and the president died eight days later.

“Reciprocal trade arrangements with other nations should, in liberal spirit, be carefully cultivated and promoted,” McKinley said. “Commercial wars are unprofitable. A policy of goodwill and friendly trade will prevent reprisals.”

Mr. Trump and McKinley also share an expansionist agenda. McKinley seized the Philippines, Guam and Puerto Rico and annexed Hawaii, making him the last president to significantly expand the U.S. footprint.

McKinley also hatched the plan for the U.S. to build a shipping route through South America to ease travel from the Atlantic to Pacific oceans. It ultimately became the Panama Canal under Roosevelt.

Mr. Trump hasn’t been shy about his expansionist agenda, talking about annexing Canada and buying Greenland. The apple of his eye remains reclaiming the Panama Canal, which the U.S. built, but turned over to Panama under former President Jimmy Carter.

Mr. Trump has said China’s influence over the canal is costing the U.S. billions in trade and threatens national security. Beijing has disputed Mr. Trump’s claims that it is pressuring Panama for greater influence over the canal.

“The first stirrings of the Panama Canal began under McKinley, and now, Trump wants it back, bringing his fascination with McKinley full circle,” Mr. Shirley said.

The analogies extend to immigration policy, with both presidents railing against immigrants who they labeled threats to the U.S. while shifting their policies because of economic considerations.

McKinley refused to allow the “debased and criminal classes of the Old World” to enter America, referring to the anarchists and terrorists of the 1890s. But he was also open to immigrants who produced wealth and committed to the country’s values, saying he welcomed immigrants who “seek to become citizens.”

McKinley argued that the economic growth and diversification brought by immigrants would benefit the country.

Mr. Trump has cracked down on immigrants entering the U.S. illegally and deported 527,000 migrants as of late October, according to Homeland Security Data.

But Mr. Trump has also reversed some of his anti-immigration policies over fears it could disrupt the economy. In June, Mr. Trump said ICE agents should avoid enforcement at work sites in certain industries, including hotels, restaurants and farm operations.

Mr. Trump also paused the deportation of 500 workers, most of them South Korean citizens, after the move threatened to undercut a lucrative trade deal he was trying to achieve with Seoul.

The two presidents also shared a desire to make it easier to fire government employees. McKinley entered office with Republicans angry that his predecessor, Grover Cleveland, a Democrat, expanded the merit list of officeholders. Cleveland’s move created a whole class of entrenched civil servants who could only be removed for cause or merit. McKinley immediately issued an executive order removing roughly 4,000 positions from that list.

The order parallels an order signed by Mr. Trump in January that reclassified tens of thousands of career civil servants as “at will” employees, removing protections and making them easier to fire.

Mr. Trump also fired thousands of government workers through his Department of Government Efficiency initiative that aimed to reduce the size of government.

![Scott Bessent Explains The Big Picture Everyone is Missing During the Shutdown [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Scott-Bessent-Explains-The-Big-Picture-Everyone-is-Missing-During-350x250.jpg)