For many children, the experience of getting their first pair of glasses is an inevitable milestone, the first in a lifetime of visits to the eye doctor.

But what if those lenses could actually help preserve the child’s vision and reduce the chances for more serious eye problems in adulthood?

That’s the promise of a new type of lens approved by the Food and Drug Administration in September. While the technology has previously been available in Europe, Asia and other parts of the world, it’s now rolling out in the U.S.

Here’s what to know about the new approach.

Myopia, commonly called nearsightedness, is when people can clearly see objects at close range but struggle with distant objects, which often appear blurry or indistinct.

Studies conducted around the world have shown rising rates of myopia, which researchers have associated with increased time indoors looking at screens, books and other objects held close to the eyes.

In the U.S., 30% to 40% of children will have myopia by the time they finish high school, according to Dr. Michael Repka, a professor and pediatric ophthalmologist at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

Until now, doctors had few options for treating the condition.

“It was typically and simply: ‘Your child needs to wear glasses and they’ll live with it,’” Repka said. “’It will be lifelong and it will likely get worse over the next few years.’”

The specialized glasses, sold under the brand Essilor Stellest, are approved by the FDA to slow nearsightedness in 6- to 12-year-olds.

The FDA said it cleared the lenses based on company data showing children experienced a 70% reduction in the progression of their myopia after two years.

Over time, myopia causes the eye to grow longer, worsening vision and increasing the risk of tears to the retina – the light-sensitive tissue at the back of the eye that is essential for vision.

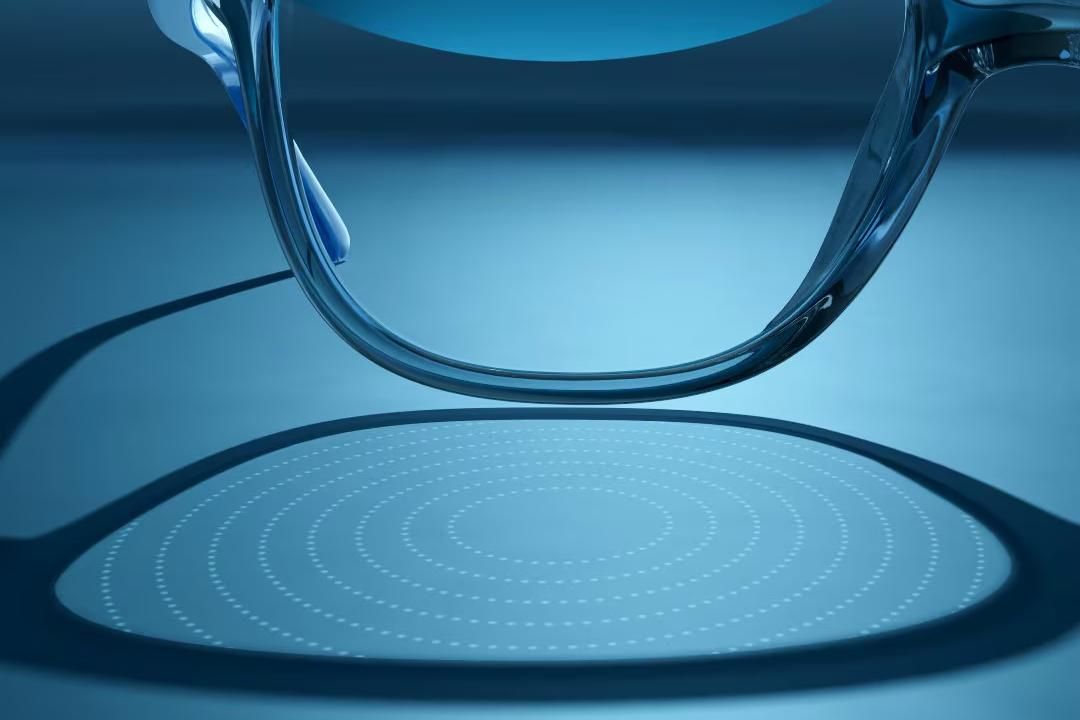

The new lenses use 11 concentric rings filled with tiny raised dots to refocus light onto the retina in a way that is believed to slow elongation of the eye.

“Whether this hypothesis is ultimately proven to be true, of course, matters only in part,” Repka said, noting that the lenses appear to work regardless of how the underlying science works.

In the company study, children wearing the lens showed a 50% reduction in eye lengthening when measured after two years. Currently, researchers in the U.S. and other countries are conducting their own independent studies to confirm those results.

Ophthalmologists say the potential benefits go beyond preserving vision to heading off some long-term consequences of severe myopia, which can include cataracts, glaucoma and retinal detachment that can lead to blindness.

“Now we have a way to slow that down and maybe we can prevent kids from having that really elongated eye that puts them at risk for blindness,” said Dr. Rupa Wong, a Honolulu-based pediatric ophthalmologist.

The suggested retail price is $450, according to EssilorLuxottica, the company that makes the lenses.

Major U.S. vision insurance providers are expected to cover the lenses for children who meet the prescribing criteria.

The only other FDA-approved product to slow myopia are contact lenses made by a company called MiSight. The daily disposable lenses, approved in 2019, use a similar approach intended to slow the progression of nearsightedness in children ages 8 to 12.

But Gupta says many parents and physicians are likely to prefer the glasses.

“A lot of people might be hesitant to put a child as young as 8 in contact lenses, so the glasses offer a really nice alternative,” she said.

Some doctors prescribe medicated eye drops intended to slow myopia, but those are not approved by the FDA.

Under the FDA’s approval decision, the lenses can be prescribed to any child with myopia who’s within the recommended age range. There were no serious side effects, according to the FDA, although some children reported visual disturbances, such as halos around objects while wearing the lenses.

The studies that the FDA reviewed for approval were conducted in Asia. Repka said U.S. ophthalmologists and optometrists may want to see some additional research.

“I think before it becomes widely used, we will need some data in the United States” showing that the lenses work, said Repka, who is conducting a U.S.-based study of the new lenses supported by the National Institutes of Health.

___

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Department of Science Education and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.