The Trump administration moved Wednesday to accelerate the development and availability of a broad class of low-cost, competitive drugs that promise to cut billions of dollars in U.S. spending on pharmaceuticals for diabetes, cancer and other conditions.

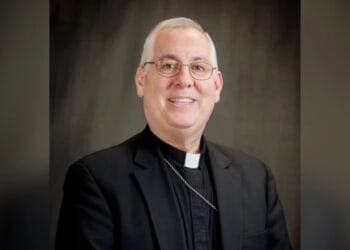

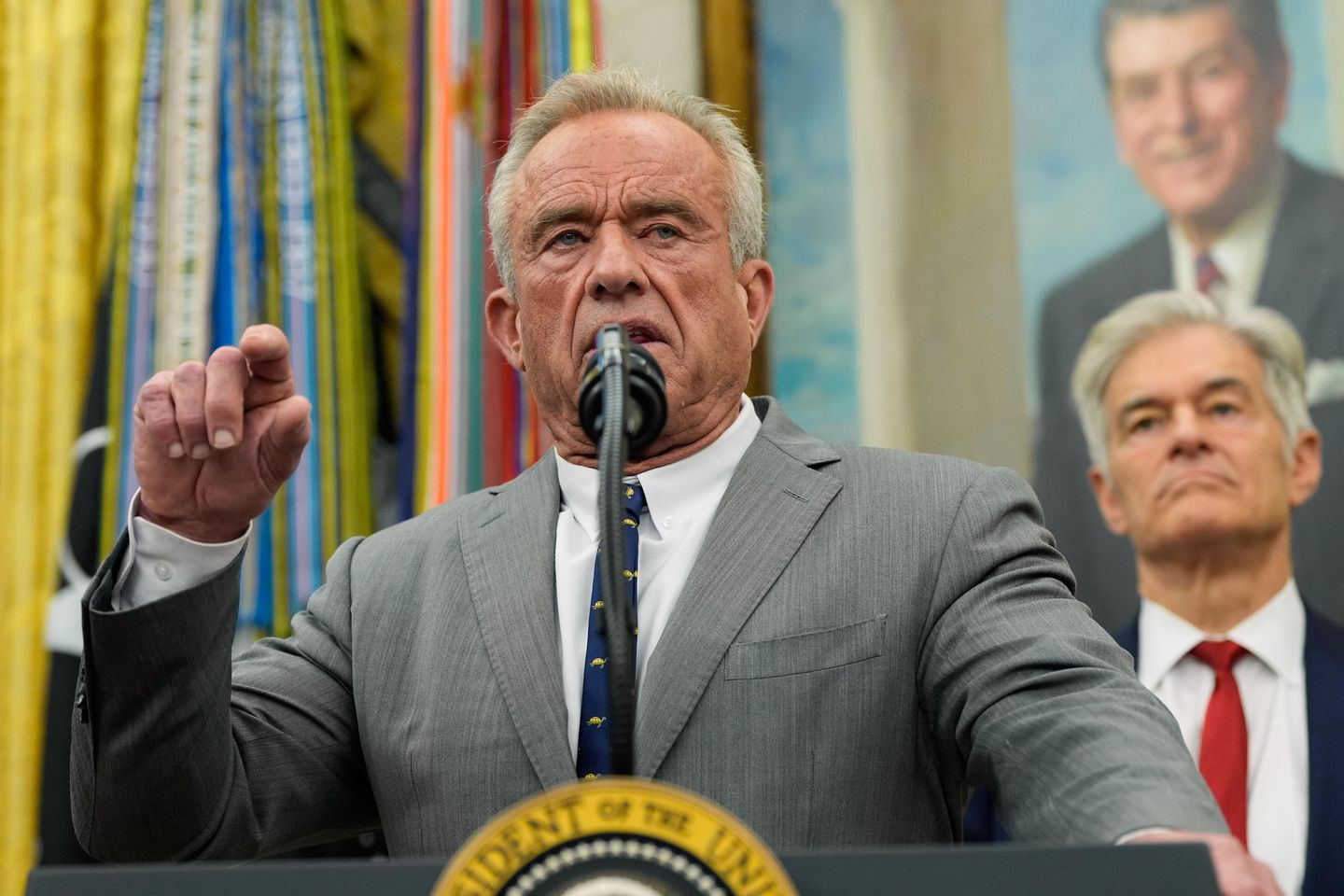

Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. said the Food and Drug Administration will streamline the development of biosimilar medications, which are essentially a cheaper, generic version of expensive biologic drugs such as Humira, Avastin and Botox, which made up more than half of all U.S. drug spending last year.

The lower-cost drugs have been bogged down in government red tape and legal loopholes, adding years to development and market access, Mr. Kennedy said during an event Wednesday in Washington.

“The FDA is outdated and burdensome. Its approval process has slowed down the entry of biosimilars, the lower-cost, equally safe alternatives to brand-name biologics,” Mr. Kennedy said. “And even when biosimilars do get approved, current laws often prevent pharmacists or patients from substituting them for the patients who would benefit from a more affordable option. That all ends today.”

The changes mark another step in the Trump administration aimed at lowering the cost of prescription drugs.

The president recently announced deals with Pfizer and other drug manufacturers to make drugs available at “Most Favored Nation” prices. The agreement has so far lowered the price of several drugs Xeljanz, a widely used medication that treats arthritis.

Competing drugs for biologics will also lower costs, Mr. Kennedy said.

Biologics are a class of drugs that are not chemically synthesized and are instead developed from living organisms, such as human or animal cells, proteins and genetic materials. While biologics make up a fraction of all drugs on the market, their cost can be astronomical, and FDA approval takes much longer than for standard generic drugs.

By speeding the approval process and getting biosimilar drugs to the market more quickly, Mr. Kennedy said, prices will come down.

He cited as an example a cutting-edge treatment that can essentially cure sickle-cell anemia. The gene-therapy biologic approved by the FDA in 2023 comes with a price tag of $2.2 million per patient. Medicare and Medicaid cover the cost of the treatment, but only in a handful of states due to the high price of the drug.

“If we can get a generic drug, a biosimilar that does the exact same thing for a fraction of the cost, we can make that treatment available in every state,” Mr. Kennedy said. Insurance companies would also be more likely to cover the cost of the treatment because it would be cheaper than treating the disease over the long term.

Other examples of biologic drugs include Humira, a treatment for rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn’s disease, Avastin, which treats cervical, colorectal, lung and other cancers, and the breast cancer treatment Herceptin.

The biologic Lantus, a long-acting insulin injector taken by people with diabetes, costs about $500 for a pack of five pre-filled pens for those not covered by insurance. Two biosimilar drugs were recently approved by the FDA and are available to purchase, but they are almost equally as expensive.

Mr. Kennedy said additional generic alternatives will ultimately make biologics such as Lantus much cheaper.

He blamed the pharmaceutical companies for slowing down the approval of biosimilar drugs and said they spent hundreds of millions of dollars lobbying Congress more than a decade ago to ensure generic alternatives would be more difficult and expensive to approve.

The results were costly.

Between 2013 and 2021, U.S. spending on biologics grew from $100 billion to $260 billion. By 2024, it topped $407 billion and for some individual patients, drug costs amount to $500,000 or more annually.

“That’s not a health care system, that’s a hostage crisis,” Mr. Kennedy said.

Chanse Jones, a spokesperson for PhRMA, the association representing pharmaceutical companies, said the high cost of biosimilars stems from pharmacy benefit managers who “are excluding lower-cost generics and biosimilars from coverage.” He also pointed to a U.S. drug pricing program that he said “creates disincentives for hospitals to use biosimilars, which drives up federal costs.”

![Keith Ellison Caught Promising to Fight State Agencies for Somali Fraudsters [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Keith-Ellison-Caught-Promising-to-Fight-State-Agencies-for-Somali-350x250.jpg)