Sam Collins is Head of Public Affairs for Popular Conservatism.

The great dictum of German Field Marshal Albert von Schlieffen, author of the German plan for invading France during the Great War was “Remember, keep the right flank strong!”

The subsequent revision of his plan by his successors, weakening the right flank to shore up the centre, is considered to have been a key factor in the failure of the overall strategy and what condemned the continent to four years of trench warfare.

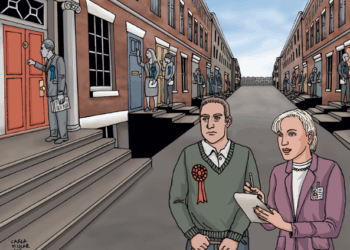

Obviously the comparison can only be stretched so far (although it is amusing to imagine Reform in the role of Belgium in our scenario), but this week has seen a range of commentators, including former independent candidate for South West Herefordshire David Gauke, arguing for a similar change of strategy by the Conservative Party. By moving leftwards, they argue, we can regain votes from the Liberal Democrats and Labour lost in 2017 and 2019 and (somehow) offset the need to regain votes from Reform.

This refrain is a well-worn one from those who believe that we can rebuild the Cameron electoral coalition that took us to victory in 2015.

However this is a mirage of a strategy, one that completely fails to recognise the different political and electoral world we inhabit in 2025.

The first reason to raise an eyebrow at this idea is simply that we have been here before. For two decades under Cameron and his successors we talked left on climate and diversity, offering mandatory gender pay gap reporting, renewable energy subsidies and electric car mandates. And what did it get us? Environmentalists and committed social justice warriors either stayed away or jumped ship as soon as an alternative electoral vehicle such as the Greens, Lib Dems or Corbynite Labour Party appeared on the horizon.

Another reason to doubt the Gaukeian strategy is a fairly obvious one: Brexit. The rights and wrongs of Brexit have been discussed ad nauseum, but one thing should be clear to anyone suggesting bringing those voters back into the fold. If a voter left the Conservatives due to our position on Brexit in 2017 or 2019, then the type of policy lurch necessary to bring them back on board will be all but impossible for us to put forward. At the very least it would have to include some acceptance of free movement of people (perhaps as part of a rejoining of the single market). And even this will struggle to convince Remainers and Rejoiners of our sincerity.

After all, if we cannot ‘out-Farage Farage’, we also cannot out-Europe the Liberal Democrats.

Furthermore, the idea that we can abandon our right flank on issues like migration and identity is for the birds.

The political realignment that has been a major part of our elections since 2015 means that the key dividing line has changed from economics to identity. For all the talk of their being a gap in the political marketplace for a Cameroon-style ‘centre right’ Party, there is not a sufficient large gap for a pro-migration, pro-Europe, economically sound party to compete for Government. If those pushing this case were open to the Conservatives becoming like the ACT Party in New Zealand, or the Free Democrats in Germany – appealing to a small wedge of voters in London and the leafy shires and competing with the Liberal Democrats for third party status – then perhaps this might be a path forward. But this seems rather an unattractive prospect.

Does this mean we should try to ‘out-Farage Farage’? Not at all.

Not only is it impossible but it is also undesirable to try. Our offer has to be that we know what is wrong, that we failed over the last fourteen years (the idea that the failings of the Conservative Party were limited to three years of Boris Johnson and six weeks of Truss is an insult to the intelligence of the average voter) and therefore we actually have policies that will put those failures – and other trenchant but tangible problems – right.

Part of this means, per Schlieffen, keeping the right flank strong. If we want to be listened to on economics, we have to at least mitigate the Reform threat on identity and migration. This means properly thought out policies that will achieve many of the similar aims that Reform purports to want, but that are actually workable. This means a policy that stops the ECHR from being a magic wand that can be deployed against reasonable deportation, a migration policy that appreciates (as I, as a migrant, do) that coming to this country is a privilege rather than a right, and that allows us to properly test migrants on their age in order to protect our vulnerable children.

But we must go further in the short term than we have in proving our seriousness on these issues.

Having a well-thought out and government-ready policy document is important, but we must willing to provide the public with a middle ground between generic philosophy (“we need to cut migration”) and a KC-led six-month policy commission. The gap between the two is where Reform have set up their stall, and every half-thought out policy from them makes it look like they are setting the agenda, and that our policy (when it comes) is nothing more than a cynical effort to steal their clothes, rather than a sincere change of direction from the last fourteen years.

Failing to shore up the right flank simply means that millions of people who either left for Reform or sat out the 2024 Election will not even give us a hearing on economic and other issues.

Simply put, the Cameroon coalition is gone, and no amount of wishing will bring it back.

![Donald Trump Slams Chicago Leaders After Train Attack Leaves Woman Critically Burned [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Trump-Torches-Powell-at-Investment-Forum-Presses-Scott-Bessent-to-350x250.jpg)