Terence Kealey is an emeritus professor of clinical biochemistry at the University of Buckingham.

Prof Kealey wrote on ConHome an article about India under the British that referenced historian Lord (Andrew) Roberts. Andrew wrote a reply in which he disputed Prof Kealey’s assertions about the Raj. This article is a reply to that refutation.

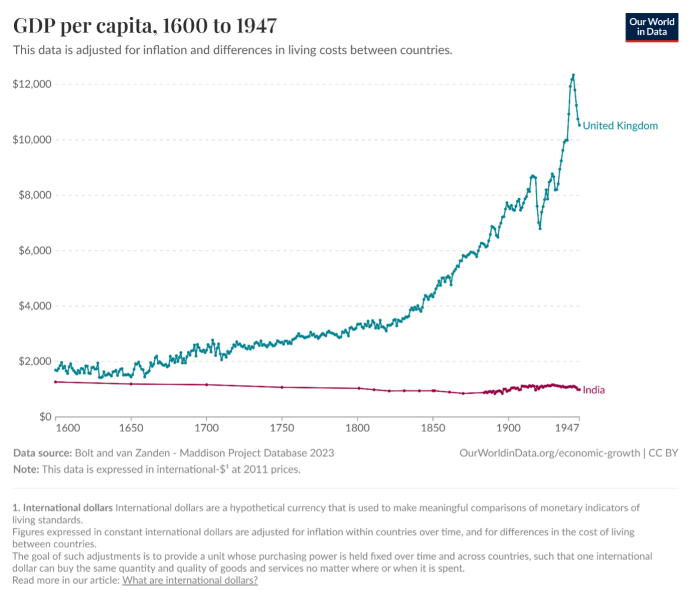

The most devastating graph in British imperial history shows how GDP per capita in Britain shot ahead during the Industrial Revolution at a time when Indian GDP per capita stagnated, which was a divergence that culminated in the Bengal famine of 1943 when up to three million people died of starvation.

The East India Company was founded in 1600, and as late as 1650 UK GDP per capita was only 22% greater than India’s. Yet by 1947, the year of Indian independence, it was 969 per cent higher.

Only after 1947 did Indian GDP per capita start significantly to rise, and in 2022 India’s GDP per capita was 685% higher than in 1947—and people no longer die there of mass starvation.

Moreover, India has been converging on the UK, and in 2022 UK GDP per capita was only 395 per cent higher than India’s. So the conclusion is overwhelming: when we ruled India it did not share in our economic wellbeing; only after we left did its economy start to recover and grow.

The question therefore is: what did the British do wrong? And the well-known answer is provided by the term ‘de-industrialisation.’ That India de-industrialised relatively is crushingly obvious, and David Clingingsmith and Jeffrey Williamson from Harvard have shown that, whereas India produced about 25 percent of world industrial output in 1750, by 1900 it was producing only 2 percent. But India also de-industrialised absolutely, and Clingingsmith & Williamson have shown that the share of the workforce engaged in manufacture fell from 15-18 per cent in 1800 to only 10 percent in 1900. Why?

The causes were course multifactorial. So, the fall of the Mughal empire was an endogenous source of damage to the Indian economy, while the forced transfers of wealth from India to Britain were an exogenous (ie, British) source of damage. In the words of the doyen of economic history, Angus Maddison:

The “drain” of funds from India to the U.K. which occurred under British rule … was a substantial outflow which lasted for 190 years. If these funds had been invested in India they could have made a major contribution to raising income levels.

Another source of damage was, of course, the pair of British Calico Acts, which forcibly transferred India’s once-flourishing textile industry to Lancashire. But another source of damage was Britain’s neglect of Indian irrigation.

Andrew Roberts writes that “by 1942 there were 57 million acres of irrigated land in British India, of which 32 million was irrigated from public works,” yet there are some 710 million acres of arable land in the subcontinent, and on page 58 of her book Bishnupriya Gupta quotes official British government statistics to show that, in 1886, 16.5 per cent of British Indian agricultural land was irrigated, which by 1936 had risen to only 19.7 per cent.

Roberts’s mighty engineering works had increased India’s irrigated agricultural land by little more than 3.2 per cent.

Even worse, Indian agricultural productivity—uniquely in Asia—actually fell under the British. Here is Maddison again:

“In the last half century of British rule for which agricultural statistics are available, there is evidence of a substantial drop in farm output per head of population. Per capita output of crops, livestock, and fisheries fell 15 per cent from 1900-3 to 1944-6. There was also a drop in wheat exports and a rise in rice imports, so that at the time of independence, India was a net importer of grain. This stagnation in farm output was unique to India, and did not occur elsewhere in Asia.”

And on page 47 of her book, Gupta again quotes official British government statistics to show that, in 1910, yields per acre of wheat, barley and rice, were only about 80 percent of the yields in 1600.

Andrew Roberts has taken a particular line on the major geopolitical challenges of our time—he has a soft spot for Lord Halifax, he justifies Eden’s actions in Suez, he supported the invasion of Iraq, he is a Brexiteer, and he currently defends the actions of the IDF in Gaza—and one aspect of his philosophy was revealed in a 2019 interview in The American Interest where he backed Brexit with: “It’s not the economy, stupid.”

The interviewers summarised his views as “It’s a much more complicated thing to do with identity.” Roberts is man of identity not of sophistry, economics or calculation. Equally, I wonder if the British imperial apologists have not bound up their identity with the idea of a noble Pax Britannica, and I wonder if that isn’t a misreading of the historical record, for the Europeans of all nationalities who created the overseas empires conquered not in a spirit of philanthropy but of avarice.

Towards the end of the imperial adventure, as increasingly-liberal and increasingly-democratic jurisdictions back home in Europe tried to ameliorate the damage of the early colonialists, attempts were of course made to repair some of the harm. The East India Company, for example, was dislodged in 1858. But official British government statistics confirm that, even during the last 50 years of the Raj, the authorities were reinvesting from revenues about 8 times more on the railways (preferentially valuable to the British colonialists) than on irrigation (preferentially valuable to ordinary Indians.)

Niall Ferguson, Jacob Rees-Mogg, Andrew Roberts and Nigel Biggar are of course right in the particular benefits they identify in the British empire, but the final judgement on that empire has already been delivered by George Orwell, who was born in imperial India as the son and grandson of imperialists, who for five years in Burma was himself an imperialist, and who—as a man of high ethics—damned the whole imperial enterprise as irredeemably flawed (and who, when most of his fellow countryfolk were appeasing, fought in Spain.)

There is a strain of conservatism that embraces the sophists, economists and calculators, and it’s a strain that draws inspiration from Adam Smith who, as long ago as 1776, decried empire and enjoined us to decolonise the British body politic.

![Steak ’n Shake Mocks Cracker Barrel Over Identity-Erasing Rebrand [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Steak-n-Shake-Mocks-Cracker-Barrel-Over-Identity-Erasing-Rebrand-WATCH-350x250.jpg)

![Mount Rushmore Could Get Trump Upgrade Under GOP Push [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Mount-Rushmore-Could-Get-Trump-Upgrade-Under-GOP-Push-WATCH-350x250.jpg)

![Soros Network, Others Behind LA Riots [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Soros-Network-Others-Behind-LA-Riots-WATCH-350x250.jpg)

![Human Trafficking Expert Details Horrific Biden Admin Endangerment of Migrant Kids [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Human-Trafficking-Expert-Details-Horrific-Biden-Admin-Endangerment-of-Migrant-350x250.jpg)