This week the nation’s premier museum on the American Revolution in Philadelphia unveiled its landmark exhibition Declaration’s Journey, tracing how America’s founding text traveled — physically and ideologically — far beyond Independence Hall. For anyone who loves liberty’s global story, it is a must see. The exhibit, arriving just ahead of America250, reminds us that Thomas Jefferson’s words once stirred imaginations well beyond the young United States — even reaching lovers of liberty in a small Central European kingdom under Habsburg rule.

Parallel Struggles Across Continents

In the late eighteenth century, Hungarians faced a familiar dilemma: defending hard-won local rights against an ambitious imperial ruler. Just as Britain levied new taxes and governors, Emperor Joseph II tried to centralize power, abolishing Hungary’s county assemblies and imposing German as the language of administration.

Kossuth toured the United States in 1851–52 … Coins struck in his honor called him … the “George Washington of Europe.”

Reformers like economist Gergely Berzeviczy drew inspiration from America’s Revolution. In 1789, he told fellow Freemasons: “England, the home of liberty … still treated its American colonies with oppressive tyranny. The results are validated. For us, the Americans are the embodiment of a courageous free people.” Owning a copy of the Declaration of Independence, he argued that the Habsburgs had broken their implicit “contract” with Hungary, echoing Jefferson’s observations about when it “becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another.” Vienna’s “long train of abuses and usurpations” mirrored Britain’s.

József Hajnóczy, a Lutheran reformer, took particular interest in Jefferson’s Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom. He attached his own Latin translation to a 1791 constitutional tract so legislators could study it firsthand — no small act in an era of Habsburg censorship.

A Travel Book That Shook a Generation

By the 1830s, America was no longer an experiment but a beacon. Transylvanian writer Sándor Bölöni Farkas toured the United States, then published Journey in North America (1834), which contained the first Hungarian translation of the Declaration — appearing even before Democracy in America reached Europe. He marveled that Jefferson’s text “summons Americans to a political creation, to the framing of a just government.” His book sold out two editions before censors banned it, but not before shaping an entire generation of Hungarian reformers.

Count István Széchenyi, dubbed “the Greatest of the Magyars,” devoured Bölöni’s account. Mocked in Vienna as der Amerikane for often citing Benjamin Franklin and George Washington, he longed to see “the Land of the Future.” When a Milanese manufacturer called him “the Washington of Hungary,” he replied wistfully: “If it were only true, Sir.”

Hungary’s Own Declaration

When revolution erupted in 1848, Jefferson’s writings became a template. Lajos Kossuth’s 1849 Hungarian Declaration of Independence mirrored America’s: a lofty preamble, a litany of Habsburg abuses, and a final claim to Hungary’s natural rights. Critics mocked him for copying Jefferson; he shrugged and sent a copy to U.S. President Zachary Taylor, hoping for recognition. Though the revolution was eventually crushed by Russian armies, the symbolic bridge to America was built.

Memory and Meaning

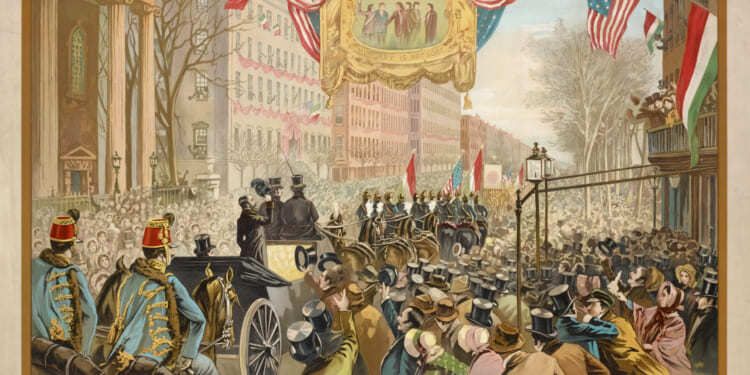

Exiled, Kossuth toured the United States in 1851–52, drawing massive crowds from New York to St. Louis. Coins struck in his honor called him the “father of European democracy” and the “George Washington of Europe.” Americans compared him to their own Founding Fathers; he in turn thanked them for proving liberty could not only be declared, but sustained.

Decades later, Hungarian Americans raised funds for a bronze statue of George Washington in Budapest’s City Park (unveiled 1906), a monument to shared ideals and one of the most elegant tributes to America’s first president abroad.

As Declaration’s Journey invites visitors to see Jefferson’s text anew, it is worth recalling how deeply those words once penetrated other parts of the world. For Hungarians, the Declaration was never just parchment in a distant land; it was proof that a people could claim their natural rights, daring to be free. That story still binds Philadelphia and Budapest across centuries and continents, as well as languages and cultures — a shared heritage for future generations to cherish.

READ MORE:

Nature and the God of the Declaration of Independence

The Cynical Talk About a ‘Constitutional Crisis’

The Real Meaning of Independence Day

George Bogden is a Senior Fellow at the Yorktown Institute and the Steamboat Institute, as well as Senior Counsel at Continental Strategy.

Anna Smith Lacey is executive director of the Hungary Foundation, a Washington-based cultural and education foundation.

![Florida Officer Shot Twice in the Face During Service Call; Suspect Killed [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Inmate-Escapes-Atlanta-Hospital-After-Suicide-Attempt-Steals-SUV-Handgun-350x250.jpg)