Body”>Both the faith tradition based on the Bible and the philosophic tradition that started in ancient Greece teach the importance of balance and moderation. In all aspects of human life and behavior as well as in the natural world of which humanity is a part, we can observe this principle at work. Too much or too little of almost anything is less than ideal.

We are already created in the divine image and every moment not acting in recognition of it is a failure.

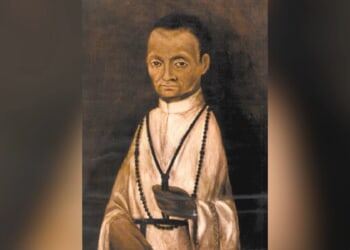

We explored last week how Moses Maimonides applied this principle as a practical mode of guidance. An extraordinary character, Maimonides had world-class competence in many fields. As a scholar of law, his reputation crossed all boundaries: his monumental code of law, the Mishnah Torah, is a landmark in legal history and influenced subsequent legal scholars such as the founder of modern international law, Hugo Grotius, and the supreme English Common Lawyer, John Sweden, among many others. His medical skill was testified to by his employment as court physician of the Mameluke sultan, Saladin, and by his nearly forty treatises on medical topics. His skill as a politician was manifest in his leadership of the Egyptian Jewish community and his ability to guide the embattled Yemenite Jewish community from afar in its successful fight to survive persecution and inner fracturing.

Maimonides taught how to employ the principle of balance as a basic skill for the simple citizens of his community; he knew it was not merely an abstract observation. Both now and then, those who would be healthy and contributing members of the body politic need to use this skill to guide their own path, taking on the practical responsibility for their own character development.

Self-guidance, certainly, but for the citizen sovereign, who expresses his conception of inner worth by assuming responsibility beyond a narrow selfishness. This was not for the citizen consumer, as the marketable products of self-help gurus pandering to our incipient inner narcissist.

Maimonides understood as Aristotle that man is a political animal — we naturally associate in communities. In the Biblical narrative, though God starts by summoning an individual couple, Abraham and Sarah, He promises that they will grow into a nation, a people in the sense that word was used by the American Founders and Framers as well. And so Maimonides teaches that the application of this principle of balance naturally extends beyond the isolated individual into the nested webs of associations that make up our life together with others, leading even to the national association, and ultimately to the vision of a kingdom of God encompassing all creation.

At each level, from the personal to the family, to the larger associations of communities and nations, the principle of balance applies. And among all the tasks awaiting its application, there is no more fundamental balance that needs to be struck than the balance between self and other.

Our American Constitution is an astonishing example of such balance. It begins with “We the people,” telling us that the sovereignty of this nation resides in its people, not in its governmental structures or in any individual whom those structures may empower. In its enterprise of establishing “a more perfect union,” it starts instead from the divine power invested in each individual, on the common level of our shared humanity. We choose to include each other in our personal concerns by devolving our God-given sovereignty upon a national government, whose power we choose in advance to accept as long as it follows this Constitution, which forever reserves to us its ultimate sovereignty.

The basis for focusing on this most important balance between self-interest and responsibility to others predated both the Constitution’s Framers and Maimonides. The Mishnah, complied around the year 180 of the Common Era in the Holy Land, records a teaching of a rabbi named Hillel who lived two hundred years earlier: “If I am not for myself, who will be for me? But if I am for myself only, that what am I?”

No one else can be ourselves. We are each a unique and irreplaceable expression of the divine image and so of infinite worth.

But what kind of a person, let alone divinity, are we if we exclude everyone else from our essential concern? Blessed with such a gift, it is a betrayal of our own selves to show our concerns limited to an inadequate conception of self. Worse, it is blasphemous, showing that we think the One in whose image we are created is both myopic and sclerotic in His personality.

Hillel added one more sentence to this line of thought: And if not now, when?

He was saying: effecting this balance is urgent. This is not a parlor game or an academic’s airy hypothesis. We are already created in the divine image and every moment not acting in recognition of it is a failure, a concealment of the divine light our lives were created to shine into the world. We cannot afford to give up any time to either selfishness or the vain imagining that someone or something else will provide us with the identity we already have waiting for us to know and to engage.

This is the galvanizing idea of “sacred honor,” the words with which the American Declaration concludes. The soul of humanity has within it a charge: to live a life worthy of the divine gift that it is. It is our honor to bear the divine image, a sacred honor. We were created to live a life worthy of the gift. The American experiment is the attempt to realize that on a national level.

But in a new way. Not a nation whose sovereignty is granted only by a king ’s condescension, or by the imperious structure of a faith unwilling to grant the divine image and national rights to none except its devotees.

Rather, it is built on the simplest and most straightforward understanding of the biblical text — all humanity is created in God’s image and so endowed with His sovereignty and His spirit, which is both incomparably individual and incomparably universal. Therefore, the freedom to be ourselves and worship God as we hear His call goes together with the broadest union of similarly free people, hearing the call to express the divine freedom in our political life. We freely commit each moment, in the eternal now, to our great common cause, each unceasingly devoting all our unique gifts to achieve together that more perfect union.

READ MORE from Shmuel Klatzkin:

Socrates, Maimonides, Lincoln, Churchill — and Us

Friends May Betray Us, but Choose Agency