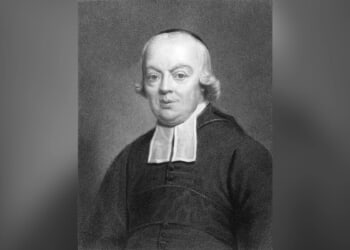

The Catholic Church will soon have a new Doctor of the Church: the English convert, theologian, author, and poet St. John Henry Newman. The Holy See announced the decision Thursday, although an exact date has not yet been announced for officially conferring the title upon the Saint. Originally an Anglican priest, Newman was a member of the influential Oxford Movement, which sought to restore certain Catholic teachings and traditions to the Church of England.

One of the most distinctly Catholic aspects of Tolkien’s work is the sacramental nature of the world he created.

He controversially converted to Catholicism in 1845 and was quickly ordained a priest and later made a cardinal by Pope Leo XIII, establishing the Oratory of St. Philip Neri in Birmingham. Although Newman was himself a distinguished author and poet, he also influenced one of the best-known Catholic works of fiction: The Lord of the Rings.

When J.R.R. Tolkien, who would later write The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, was a child, his mother, Mabel, converted to Catholicism, bringing the young Tolkien and his brother, Hilary, into the Church with her. Due to her conversion, Mabel found herself shunned by much of her Anglican family and slowly wasted away, dying when Tolkien was only 12 years old. She left her children to the care of a Catholic priest, Fr. Francis Xavier Morgan of the Oratory of St. Philip Neri, who became their legal guardian.

Tolkien was partly educated by Morgan, who was himself educated by Newman as a child. In fact, Morgan was only the third student who entered the primary (elementary) school at the Oratory of St. Philip Neri, well before Newman was elevated to the College of Cardinals. Years later, shortly before entering the priesthood himself, Morgan accompanied the newly-minted Cardinal Newman during his stay at the London residence of the Duke of Norfolk, a descendant of Elizabethan-era Recusants and the most prominent Catholic member of the English nobility.

Newman’s influence on Tolkien’s work is both visible and profound. Both laid particular emphasis on beauty and truth, as well as the moral imagination and a sacramental perception or ordering of reality. In Newman’s writings, particularly An Essay in Aid of a Grammar of Assent, which took the Saint two decades to write, conscience is classified as a function of the moral imagination: more than a purely rational act, the exercise of conscience relies on imagination to connect the self to God’s moral law, through knowledge, intuition, experience, and reflection.

Newman also introduced the “illative sense,” a mode of reasoning that integrates the moral imagination to reach moral and religious certainty. In particular, imagination is used as a means of bridging otherwise unspannable gaps between abstract principles and concrete realities and experiences, yielding a more complete vision of truth.

The English Saint further promoted and clarified a “sacramental worldview” or sacramental view of reality, positing that the material world is imbued with divine meaning. “This world is not simply a veil, but a sacrament, a type, a figure of the unseen world,” Newman wrote in his autobiographical Apologia Pro Vita Sua. In other words, God has left His signature on His handiwork, so that the visible world might point to the invisible world. The world of earth and human relationships and temporal suffering is, in Newman’s view, a means of entering into more fully the realm of eternity.

Both of those concepts — that of the moral imagination and a sacramental view of reality — are closely related to Newman’s views on truth and beauty. Truth was, of course, an essential and integral part of Newman’s work, philosophy, theology, and spiritual life. Most significantly, in An Essay in Aid of a Grammar of Assent, Newman, much like St. Thomas Aquinas before him, rejected a false dichotomy between faith and reason, arguing that truth is recognized, understood, and embraced through both rational analysis and personal assent.

Beauty, Newman insisted, is a pathway to God, a reflection of His divine nature. Wherever it is found — whether in art or music or literature or architecture or the liturgy — beauty stirs the depths of the soul and elevates the heart and mind to step over the division between the temporal and the eternal and enter into contemplation of God. In particular, as a poet himself, Newman considered literature a prime opportunity to elevate the soul by means of beauty.

Certainly, his own education in the tradition of Newman led Tolkien to apply such principles in his most seminal works, namely The Lord of the Rings, but to greater or lesser degrees in The Hobbit, The Silmarillion, and the rest of his Middle-earth legendarium. Tolkien’s profound and prodigious imagination is, in Newman’s tradition, ordered according to virtue.

A common criticism leveled against Tolkien’s work is that his “good guys” are always and clearly good, while his “bad guys” are obviously evil, even sadistic and grotesque. While such a criticism is rather inaccurate, Tolkien’s work does clearly denote what acts are good, noble, and virtuous — whether the fidelity of Aragorn, the sacrifice of Boromir, the wisdom of Gandalf, the courage of Samwise Gamgee, the perseverance of Frodo, and even, to some extent, the struggle between Sméagol and Gollum over whether or not to succumb to his obsession with the Ring — and which are evil and reprehensible — the malice of Sauron, the treachery of Saruman, the cruelty of the Orcs.

One of the most distinctly Catholic aspects of Tolkien’s work is the sacramental nature of the world he created, following again in Newman’s line of thought. In The Hobbit, when the titular hobbit, Bilbo Baggins, expresses surprise at “the prophecies of the old” coming true, suggesting that their fulfillment has more in common with mere coincidence, Gandalf replies, “Surely you don’t disbelieve the prophecies, because you had a hand in bringing them about yourself? You don’t really suppose, do you, that all your adventures and escapes were managed by mere luck, just for your sole benefit?”

This view is echoed in The Lord of the Rings, when Bilbo’s nephew, Frodo, suggests that someone wiser or stronger than he should be entrusted with the Ring. Gandalf counters that Bilbo was surely “meant” to find the Ring and Frodo is surely “meant” to have it.

Whether in obscure details unnoticeable to any but the most obsessive and voracious readers of Tolkien or more blatantly — the Elvish waybread lembas, for example — is inspired directly by viaticum, the Eucharist given to someone who is sick or close to death, and both Aragorn and Gandalf are Christ-like figures, while Galadriel is closely (although not entirely) modeled after the Blessed Virgin Mary — Tolkien has filled his world with images, symbols, and intimations of the spiritual and sacramental reality he recognized and loved as a Catholic.

Tolkien also, of course, filled Middle-earth with both beauty and truth. Again in keeping with the tradition of Newman in which he was mentored and educated, the author and Oxford professor united this beauty and truth with both the moral imagination — using the material world he imagined to span the chasms between temporal reality and eternal truths — and the sacramental worldview — beauty, in Middle-earth, is the work of God and those who abide by His law, while ugliness is the result of pride and wickedness.

For all those who feel that long-dead Saints and the “Doctors of the Church” are but musty medieval relics or irrelevant and inaccessibly pious, it is heartening to know that the newest Doctor of the Church played a pivotal role in shaping one of the most influential, most-read, and best-loved books of the past two centuries.

READ MORE from S.A. McCarthy:

Catholic Priests Must be Allowed to Visit ‘Alligator Alcatraz’

Polish Leader Attacks Bishops’ Immigration Activism

Should Illegal Aliens Be Dispensed From Sunday Mass Obligations?

![Former Bravo Star Charged After Violent Assault Using a Rock-Filled Sock in Tennessee Walmart [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Former-Bravo-Star-Charged-After-Violent-Assault-Using-a-Rock-Filled-350x250.jpg)

![Karoline Leavitt Levels CNN's Kaitlan Collins and Other Legacy Media Reporters [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Karoline-Leavitt-Levels-CNNs-Kaitlan-Collins-and-Other-Legacy-Media-350x250.jpg)

![Man Arrested After Screaming at Senators During Big Beautiful Bill Debate [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Man-Arrested-After-Screaming-at-Senators-During-Big-Beautiful-Bill-350x250.jpg)

![Illegal Alien Walked Free After Decapitating Woman, Abusing Corpse for Weeks [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/1753013138_Illegal-Alien-Walked-Free-After-Decapitating-Woman-Abusing-Corpse-for-350x250.jpg)