In the elder days of Art,

Builders wrought with greatest care

Each minute and unseen part;

For the Gods see everywhere.

Let us do our work as well,

Both the unseen and the seen

Make the house, where Gods may dwell,

Beautiful, entire, and clean.

— Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, The Builders

It is no small thing to achieve architectural perfection, but it can be done, even in these fallen days, provided the designer commands a mastery of the timeless principles of mass, space, line, and coherence, and manages to balance aesthetic and functional considerations. Sometimes it all comes together, as was the case with Steven Spandle’s classically-inspired White House Tennis Pavilion, which this year has won both a John Russell Pope Award and a Palladio Award for outstanding achievements in the field of traditional design. Such accolades are richly deserved. The graceful Doric columns, limestone cladding, and fanlight windows of the pavilion perfectly complement similar design elements present in the White House itself, while interior design touches like the the lovely groin-vaulted entry hall, the French-polished mahogany doors, the walk-out mahogany windows (subtly referencing Monticello’s Garden Pavilion), the Indiana Limestone detailing, the Georgia Grey Granite water table, the Georgia Pearl Grey marble stonework, and the symbolism-laden ornamental plasterwork all the combine in a manner altogether worthy of Jefferson, or the great Palladio himself.

Yet Spandle’s pavilion is no mere folly. The building is entirely fit for its purpose, featuring a comfortable sitting room, a kitchenette, a tennis-racket room, and a full bathroom, any of which would alone constitute a vast improvement over the old storage outbuilding that once occupied the site, a tumbledown shack so shabby it was nicknamed the “Pony Shed” by the White House ground-staff. Here we are pleased to find — adapting that old saying about thespians — that there are no small commissions, just small architects. Steven Spandle was given a seemingly trivial commission, in the grand scheme of things, and produced an architectural pearl, one which seamlessly connects the past and the present, and demonstrates how classical architecture still has an important place in a world increasingly dominated by polyvinyl chloride, custom-extruded thermoplastics, aluminum composite material, fiber cement cladding, and exceedingly poor design choices.

White House Tennis Pavilion (White House/Wikimedia Commons)

The architectural historian and critic Henry Hope Reed, in his masterful treatise The Golden City: An Argument for Classical Architecture (1959), lamented how the “daemonic forces of abstract nihilism” began to deface American cityscapes in the post-war era. “The chariot of fashion,” observed Reed, “has long since abandoned the classical path of taste and now it brings destruction on every side.” We may have deviated even further from the classical path of taste since Reed’s time, but the ancient trackway remains for all to see, in cities, in monographs, and in our collective imagination. All we have to do is take the reins of the “chariot of taste” and head in the right direction, something which is admittedly easier said than done, given the degenerate state of academia and the commercial and civic architecture industry. In theory, it should be easy to make the case for traditionalism and classicism in architecture, just as it is easy to make a case for harmonic music, with its pleasing combinations of pitches, over atonality or dissonance. As Sir Roger Scruton argued in his essay on the great Luxembourgish traditionalist architect Léon Krier, “Cities for Living,” “[t]here are no chords in modernist architecture, only lines — lines that may come to an end but that achieve no closure.” Due to the institutional capture achieved by modernists and their ilk, however, the daemons of abstract nihilism remain obstinate in their malice. Works like Spandle’s pavilion, however modest in scale, show how those pernicious spirits might finally be exorcized. (RELATED: Bauhaus and the Cult of Ugliness)

There is something genuinely daemonic about, to take one prominent example, the brutalist monstrosity that is the Barack Obama Presidential Center…

We use the term “daemons” here advisedly. There is something genuinely daemonic about, to take one prominent example, the brutalist monstrosity that is the Barack Obama Presidential Center, designed (and completely botched) by Tod Williams and Billie Tsien Architects. The future Obama presidential library has slowly grown like an excrescence on the edge of Chicago’s otherwise lovely Jackson Park, as the project hemorrhages money (an original estimate of $300 million has now reached $850 million, not including hundreds of millions more for the necessary roads and utilities) and sucks the life out of the nearby environment. Situated in a lush green space designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, the “Obamalisk” squats disgustingly, in a fashion wholly out of character with its surroundings, looking rather like the crumbling remnants of a not-very-successful alien civilization, perhaps something out of a low-budget Dune adaptation. A literal child could have done better, and indeed they do, every day in kindergartens all over the world, with Crayola markers and Stickle Bricks.

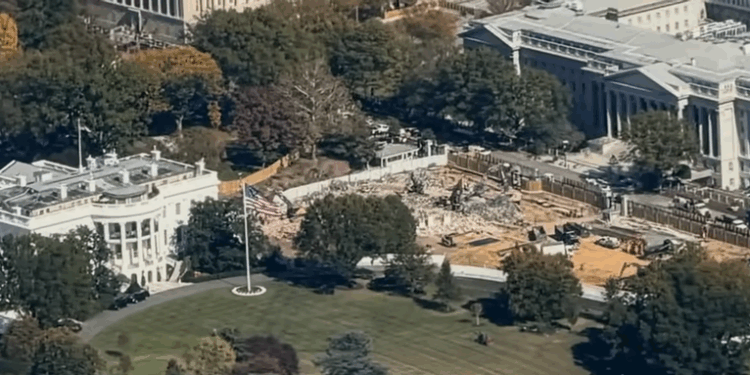

Barack Obama Presidential Center, April 2025 (Torsodog/CC0 1.0/Wikimedia Commons)

It is (almost) possible to integrate a modernist building with its local environment. Take Enric Miralles’s Scottish Parliament Building, which is butt-ugly in the main, as you would expect, but nevertheless references the adjacent Holyrood Park, using Scottish gneiss and granite, and Scottish oak and sycamore, to avoid looking like the sort of brutalist Harkonnen torture chamber currently being thrown up on the South Side of Chicago. There are two positives one might come up with regarding the infamous Obamalisk: its cost overruns and hideous aspect represent their own sort of self-flagellation; and like all structures primarily made out of concrete, it figures to have a relatively short shelf life.

Once again am I reminded of the Mitchell & Webb “Are We the Baddies?” sketch, in which two beleaguered Nazi soldiers ponder whether they might in fact be the villains of the ongoing conflict. “Have you noticed that our caps actually have little pictures of skulls on them? … Their [the Allies] symbols are all quite nice! Stars, stripes, lions, sickles… You gotta say, it’s better than a skull. I mean, I really can’t think of anything worse, as a symbol, than a skull!” One can imagine a modernist or post-modernist architect contemplating why it is that their traditionalist counterparts have the Classical orders, or Gothic rib vaults, or the sustainable, natural, recyclable building materials of vernacular architectural styles, while they have hideous failures and blunders like the Obamalisk, the Buffalo City Court Building, Boston City Hall, Pruitt-Igoe, and Grenfell Tower, among so many others.

That modernist architects never actually experience this moment of self-awareness would indicate that modernism, like other symptoms of leftism generally, may indeed be a biological phenomenon, the result of a smaller-than-normal or underdeveloped amygdala, and the attendant inability to experience a healthy disgust response. How else can we explain the decision on the part of the Obama Foundation, in conjunction with its hired architectural firm, to commission the Obamalisk on purpose? This is not a science fiction film, or a J.G. Ballard novel, but here we are, in real life, with the skyline of a great American city defaced by yet another brutalist monstrosity when we all know better by now, or should.

Hence, my lack of concern over the renovation of the East Wing of the White House, and the drummed-up controversy it has engendered in the “popular” press. James C. McCrery II, the architect in charge of the upgrades, has a fine track record of designing traditionalist buildings that can be constructed on time, on budget, and to the satisfaction of his patrons. McRery has, during his career, done something vanishingly few fashionably modernist architects have ever accomplished in their lives, namely to design buildings of genuine aesthetic appeal, which people might actually want to look at or be in. These include the Renaissance Revival Cathedral of the Most Sacred Heart of Jesus in Knoxville, Tennessee, tastefully clad in Indiana limestone and Roman-style bricks sourced from Ohio; the Renaissance-inspired St. Mary Help of Christians Catholic Church in Aiken, South Carolina, which won a John Russell Pope Award for its marvelous design (the pediment mosaic is a particular inspired touch); and the Gothic monastery currently being erected for the Carmelites of Wyoming near Meeteetse, with its limestone facades, delicate tracery, and soaring spires made possible (and affordable) by the use of innovative CNC fabrication on the part of the monks themselves.

James McRery is viewed as a traitor by many in the architectural community, having studied under Peter Eisenman and Jeff Kipnis at The Ohio State University in the 1980s before becoming disillusioned with the spiritual desolation of deconstructivism. Modernism, McRery decided, was “counter to God’s creation, in every aspect and in every detail,” a position which is absolutely correct, but bound to rile so many of his contemporaries. Some of his former professors have even proven willing to attack him in the press, with Robert Livesey opining that “his work does not have the presence of real classical architecture, or even of people who were also after the classical, like Palladio, or later Hawksmoor,” and Peter Eisenman criticizing the East Wing project on the grounds that “putting a portico at the end of a long facade and not in the center is what one might say is untutored.”

This is all a bit snide, and there are legitimate reasons that McRery has placed the portico where he has. The White House complex is a complex composition, and visitors will not be approaching the East Wing from a formal center line, but often from the northeast corner. Textbook symmetry may be lost, and a departure from strict axiality has indeed been made, but it is at times necessary to make concessions to topography and directions of approach. More importantly, by making the shift, McRery has ensured that another central portico does not compete with the primacy of the Executive Residence. This keeps the overall hierarchy clear and allows the East Wing portico to represent a gesture of invitation rather than of dominance, as would have been the case with a central porch. All of which is hardly “untutored,” one must admit.

We should not expect too much from Eisenman, an architect who readily admits to feeling “the need for incongruity, disharmony, etc.” in his work, and who regularly designs homes in which, as Amy Frearson noted in the magazine Dezeen, actual quality of life was “not the architect’s main concern.” Lest we forget, it was Eisenman who was roundly, even humiliatingly, trounced by the traditionalist design theorist Christopher Alexander in a famous November 17, 1982, debate at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design. It is normally a point of pride that the student has surpassed the master, but Eisenman’s poisonous dogma evidently leaves no room for that sort of grace.

In any event, the White House has long needed a suitable site for state receptions, one that can hold its own with the State Rooms at Buckingham Palace, the Salle des Fêtes at the Élysée Palace, the Palazzo del Quirinale, the reception halls of the Grand Kremlin, and other equivalent ceremonial locations, and soon it will have one. Blinkered modernist ideologues will inveigh against McCrery’s lavish ornamented interior, secure in the knowledge that had they only gotten a hold of the commission, they might have produced something so much more provocative, and so much uglier, no doubt in béton brut, and with massive cost overruns a dead certainty. They view the prospect of a future dominated by the Spandles and McRerys of the world with horror, while Posterity, I am confident, will judge the traditionalists far more kindly than the architects of incongruity, disharmony, discomfort, and civilizational self-hatred.

“The new city,” wrote Sir Roger Scruton, “is a city in which glazed facades mirror each other’s emptiness across streets that die in their shadow. The facelessness of such a city is also a kind of godlessness,” and when “the modern city enshrines the temporariness of facelessness as a permanently utilitarian way of life, then something has gone dreadfully wrong.” Something has indeed gone dreadfully wrong, but Scruton was, if anything, too generous in this case. Modernist eyesores like the Obamalisk are not failures because they are merely utilitarian. Architects like Eisenman cannot even be bothered to create Machines for Living. Amy Frearson, in her profile of Eisenman, had to admit that “[w]ith their superfluous geometries, Eisenman’s buildings are not without their problems. Reports of leaking roofs, inappropriate materials, and insufficient shading systems have plagued his career.” One might say that his very career was a plague on those of us with normal disgust responses, or basic demands for livability and functionality. That architects like Peter Eisenman, Tod Williams, and Billie Tsien have been encouraged to design buildings that are not only substandard from a practical perspective, but are aggressively and, what is more, intentionally repugnant, speaks to a deep spiritual rot that has set in among supposed bien-pensants. All of which is to say that the arrival of traditionalists like Steven Spandle and James McRery on the public scene is very, very welcome.

Modernism has eaten away at our built environment for far too long. In the depths of the Wyoming wilderness, in cities like Knoxville and Aiken, and in our nation’s capital, we are finally seeing a broader counter-offensive against the “daemonic forces of abstract nihilism” that have beset us for more than a century now, ever since misguided modernists like Adolf Loos convinced their fellow architects that ornament was a crime and beauty was surplus to requirements. I can think of no better remedy for the injuries inflicted by those malign spirits than the construction of a pretty Italianate church, a delicate little folly of a tennis pavilion, or a grand state ballroom, works that confirm the vitality of the ageless principles of classical architecture, however much that may provoke those possessed of an irrational, almost diabolical hatred of Beauty itself. We will need a great many more of such works, however, if we are ever to realize the Golden City that Henry Hope Reed prophesied would rise from the ashes of modernist folly. But if a start is to be made at all, it must be made somewhere, and the works of Spandle and McRery seem to me to be as promising a first step as could ever be expected.

READ MORE from Matthew Omolesky:

![Donald Trump Slams Chicago Leaders After Train Attack Leaves Woman Critically Burned [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Trump-Torches-Powell-at-Investment-Forum-Presses-Scott-Bessent-to-350x250.jpg)