After my most recent article on the persecution of Christians in Nigeria, a reader thanked me for describing the problem, but then offered me a direct challenge, calling for some concrete suggestions about what U.S. policy should be towards Africa. It’s a timely and important question, particularly in the wake of the recent massacre in the Congo, where dozens of Christian worshipers were struck down — many beheaded — by machete-wielding members of yet another affiliate of ISIS. (READ MORE: The Left Ignores Nigeria’s Suffering Christians While Proclaiming to Be Perfect Humanitarians)

After all, for every criticism — and I’ve criticized U.S. policy towards Africa repeatedly over the last two years — there is, or should be, at least a corresponding attempt to offer solutions. I’ve tried to do this over the last two years here at American Spectator, but the reader’s challenge deserves, at the very least, a thoughtful summary of these positions, couched in terms of answering Lenin’s famous question, “what is to be done?” (READ MORE: Biden Visits Africa Too Little and Much Too Late)

The first response is easy — stop using our instruments of influence, particularly our foreign aid dollars, to undermine local cultures.

The first response is easy — stop using our instruments of influence, particularly our foreign aid dollars, to undermine local cultures. With the exception of a handful of Western-educated elites, “colonized” — I use the word advisedly — by sojourns at places like Harvard or University College London, no one who matters in Africa wants rainbow flags and forced obeisance to “Pride” rituals. Not one of these cultures has the least desire to be “woke,” even when it comes dressed in all the usual buzzwords about democracy and spread by NGOs empowered by USAID funding. (RELATED: A Free Africa for Africans)

It’s not for nothing that Africa has become a stronghold of traditional Christianity, so much so that even Pope Francis exempted the African churches from compliance with his 2023 decree, Fiducia Supplicans, which allowed — nay, encouraged — the blessing of same sex couples. And the rainbow agenda, assiduously promoted by the Biden-era State Department, is only the most visible among many attempts by the U.S. to impose progressive values upon unreceptive African nations. Again, how ironic coming from a cohort who, in nearly the same breath, vociferously decry anything that smacks of Western colonization.

Gratifyingly, the Trump administration already has taken important steps to roll this back, notably by clipping the wings of the most egregiously woke elements hitherto supported by USAID dollars. Trump’s White House confrontation with the President of South Africa further underscored the message that, going forward, the U.S. means to take a more hard-headed approach to African issues. And Secretary of State Marco Rubio has made this new orientation explicit. (RELATED: Trump Declares Independence for USAID Recipients)

Still, one might reasonably ask the question, “hardheaded, but to what end?” Here we find the second answer to my reader’s question, albeit one less precise than he might have hoped. Going forward, we need a foreign policy that actually makes a genuine effort to understand the various African countries on their own terms — a consistent, and consistently well-informed effort. I’ve written about this before, observing that the besetting sin of U.S. policy within Africa has consisted of indifference punctuated by occasional over-excitement, coupled with an insistence on viewing every issue through our own domestic lenses.

We need to make a genuine effort to cultivate African partners, but this begins by communicating clear expectations as we cultivate these relationships.

This starts, perhaps surprisingly, by pursuing an “America First” agenda toward Africa, but one reinforced by rebuilding our expertise with respect to actual, on-the-ground conditions, in the various African countries. We need to make a genuine effort to cultivate African partners, but this begins by communicating clear expectations as we cultivate these relationships. That’s the “America First” part of the equation — we can’t expect much from any partnership when we haven’t taken the time to work out what we want from potential partners.

For too long, the message we’ve sent can be reduced to “we don’t really know what we want, we’ll get back to you when we do.” Coupled with our apparent inability to listen to potential African partners, we find ourselves simply talking past one another. For example, when we express concern about expanded Chinese or Russian influence, do we take the time to ask what the alternatives might be? Do we want an entire continent dominated by outside powers who are hostile to our interests? Are we willing to offer constructive alternatives? These are questions African leaders want answered.

When we speak to these leaders regarding our concerns about Chinese resource grabs, about how China wants to control their production of rare earths and other strategic materials, do we offer options for them to consider? Do we have an investment strategy for these products and a security strategy to ensure that American investors can count on a safe return on such investments? Do we even have a State Department capable of discussing such questions meaningfully?

At present, we still seem paralyzed by the fear of appearing as “colonizers,” when what we really have to offer is something that potential African partners want, namely, developmental support without Chinese dominance. Ironically, the worst abuses, the worst “colonization,” if you will, occur precisely in those regions where Chinese avarice dominates. The opportunity exists for American companies to earn profits, for our national security to be advanced, and for the implementation of a more humane approach to mining these materials.

Would host governments cooperate? In most instances, they know that the present situation is unstable, that continued abuse of large parts of their populations creates a veritable powder keg just waiting to explode in their faces. Ironically, our fear of pursuing profitable relationships, a fear stoked by the same elements who’ve promoted a woke cultural agenda across Africa, sets the stage for precisely the kind of political explosions we’ve learned — rightly, in too many instances — to fear.

If we are concerned about the destabilizing effects of mass immigration, then we should be similarly concerned about the emergence of Africa as a source for such immigration. We’ve focused on one source region, Latin America, and on one solution, stopping entry at our borders. But as I’ve argued previously, and in some detail, Africa may well represent a greater long-term problem. Incentivizing “stay at home” represents a more cost-effective and ultimately more humane solution. But we need to learn from past mistakes, avoiding support for expensive vanity projects while promoting the small-scale education and health initiatives upon which African entrepreneurs — and there are many such — can thrive.

But none of this can occur without addressing the elephant in the room. Once and for all, we have to take a stand against militant Islamism wherever it presents itself. For too long, we’ve viewed this through a Middle Eastern lens and failed to see how it has become a worldwide threat, including a threat not just on our doorstep, but inside our house. For example, not all the Somalis in Minnesota support a radical anti-American agenda, but Ilhan Omar is scarcely an outlier. And her hatred for the United States — can we describe it any other way — was incubated in her African homeland.

Again and again, what we’re seeing today, from Somalia to Nigeria, is not simply a murderous assault on Christianity, although it is certainly that. What we are seeing is an assault on the Western world itself, one already manifest in Europe and, with each passing day, closing in on our own interests. Whether identified as ISIL or any of many other Islamist permutations, the agenda remains the same: the creation of an ever-expanding caliphate, an instrument for spreading sharia dominance across the globe. We are right to be concerned about the global Chinese threat, but we should be equally on guard against those dedicated to the spread of Islamism.

The Biden/Obama administrations chose to minimize this. Back in 2020, the Trump administration designated Nigeria as “a country of particular concern” for the persecution of Christians. This designation was amply justified, indeed, and even then, long overdue, for what the Fulani Muslim terrorists had undertaken was nothing less than the ethnic cleansing of Christians as a first step — their own words, not mine — to creating a caliphate.

Absurdly, not long after taking office in 2021, the Biden administration lifted the “country of particular concern” designation, and, even more absurdly, labelled the entire conflict a “struggle over scarce agricultural land” occasioned by “climate change.” Intentionally or otherwise, the result was to encourage the Nigerian government’s laissez-faire approach to Fulani brutality. It’s high time for the Trump administration to reinstate the “country of particular concern” designation and signal our impatience with this nonsense.

Let’s save the facile “religion of peace” arguments for another day. There may well be many millions of Muslims who wish to live in peace, and there may be Muslim countries prepared to work with us for the common good, in such initiatives as the “Abraham Accords.” But let’s not kid ourselves. As we’re now witnessing across Europe and, sadly, on our own college campuses, radical Islamism represents the single greatest threat to peace in the world and the single greatest threat to our American way of life, indeed, to what’s left of Western civilization itself.

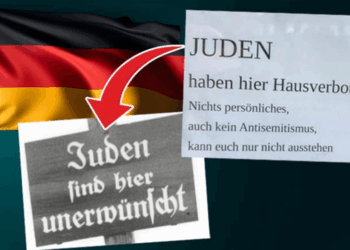

The threat is everywhere, and it is powerful. Why else would Britain, France, and Canada threaten Israel with the recognition of a Palestinian state, in effect rewarding Hamas for the October 7 pogrom? The answer lies in the influence exerted by the outsized presence of Islamist radicals within their respective political cultures. And not just there, and in other European countries beset by radical Islam. Why else have our own Democrats been so utterly lame in their condemnation of anti-Semitism? Why is it so hard for the party leadership to call out a New York mayoral candidate — think about that — for wanting to “globalize the Intifada”?

Yes, the problem is global, and the temptation, inevitably, is to simply write off Africa, but this would be a mistake. Think of how Afghanistan, much further away, much less endowed with strategic significance, became an incubator for global terrorism. The good news is that, despite the daily threats, there are strong Christian communities across the continent, communities that share our values. The better news is that many African governments, however compromised they may be in terms of Jeffersonian ideals, want no part of being submerged in an Islamist tidal wave.

In the end, we need a thoughtful and informed approach to identifying those African nations, and the communities within those nations, the ones that simply need encouragement in defending themselves and in building a better life for their people. These are the places where we should concentrate our attention. On this basis, we can begin to identify targeted assistance strategies, focusing first on those who want our help and are capable of putting it to good use. Once we build success in a few places, we can use it to draw others in the same direction.

To couch the challenge in terms of “saving Africa” casts the task much too broadly. We don’t need — and shouldn’t want — some grand “African” political or, God forbid, military initiative. They don’t need our soldiers — the continent is awash in soldiers, although often lacking in professionalism and even more often lacking in purpose or direction. We address this by focusing on providing that professionalism — this is something we know well how to do — and by encouraging their respective governments toward manageable purposes that are consistent with our own interests.

And what better purpose than countering the immediate Islamist threat, starting with protection for the Christian communities currently under attack. I can think of few better building blocks for the salvation of a persecuted people, and, ultimately, of a continent at risk. And I can think of no better purpose for an “America First” policy towards Africa.

READ MORE from James H. McGee:

The Meaning Behind ICE Agents’ Masks

The Left Ignores Nigeria’s Suffering Christians While Proclaiming to Be Perfect Humanitarians

‘Truth, Justice, and the American Way’ No Longer: The End of Superman

James H. McGee retired in 2018 after nearly four decades as a national security and counter-terrorism professional, working primarily in the nuclear security field. Since retiring, he’s begun a second career as a thriller writer. He’s just published his new novel, The Zebras from Minsk, the sequel to his well-received 2022 thriller, Letter of Reprisal. The Zebras from Minsk find the Reprisal Team fighting against an alliance of Chinese and Russian-backed terrorists, brutal child traffickers, and a corrupt anti-American billionaire, racing against time to take down a conspiracy that ranges from the hills of West Virginia to the forests of Belarus. You can find The Zebras from Minsk (and Letter of Reprisal) on Amazon in Kindle and paperback editions.

![Gavin Newsom Threatens to 'Punch These Sons of B*thces in the Mouth' [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Gavin-Newsom-Threatens-to-Punch-These-Sons-of-Bthces-in-350x250.jpg)

![ICE Arrests Illegal Alien Influencer During Her Livestream in Los Angeles: ‘You Bet We Did’ [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/ICE-Arrests-Illegal-Alien-Influencer-During-Her-Livestream-in-Los-350x250.jpg)